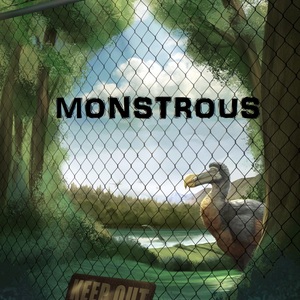

The Forgotten World

By A.J. Ponder

Dear Mr. Rutherford

Enclosed are two specimens I believe your master will find of interest. Please handle with extreme care, and do not open until after you have read Doctor William Scott’s first-hand account and can take appropriate precautions.

Sincerely,

A friend.

Our little hunting party arrived at Lyttleton wharf, New Zealand, to be greeted by our employers, Jean and Arthur Conan Doyle. They were wearing matching beige safari outfits and carrying oversized butterfly nets.

“You right, Doc?” Jean asked as Hawker, Pat and I stepped off the modern steam ship.

“Never been better,” I lied, hefting my National Museum bag with all my precious equipment over one shoulder. It had been one hell of a voyage. After so long in the boat, the ground was swaying disconcertingly.

“So, this is our cryptid capturing team?” Arthur said.

“I’m so sorry, where are my manners?” I said. “Arthur and Jean Conan Doyle, I’m pleased to introduce Hawker, the tracker of the party.”

Hawker grimaced as his hand was near shaken off.

“And this is Pat, our young artist,” I continued. “He’s obsessed with flightless birds, and can’t wait to help catch a moa.” Young Pat somehow managed to shake hands with his drawing board tucked under his arm.

“Good,” Arthur said. Well then, let’s not dally. There’s a local expert we need to meet.”

“Dammit, I don’t like locals. More trouble than they’re worth,” Hawker spat.

“No time for that,” Arthur said, practically running toward the small township nestled within bush clad hills. We all followed, past the Albion Hotel and a number of respectable establishments to the cruddiest bar I’ve ever seen. The outside was peeling paint and rustic timber. Inside was all smoke and grime. The customers, a smattering of cockies, or whatever the locals called their farmers, looked as down at heel as the bar itself.

My eye caught two lads sitting opposite an old geezer with a grizzled beard half-way down his chest.

I tipped my hat.

“Five beers,” Jean ordered.

“Ah, tea, for me,” Pat said.

“It’s beer, or beer,” the man behind the counter growled.

We each took a mug, then sat down next to the locals, cozy like. Within moments, Pat had pulled out his sketching pad and was drawing giant birds again.

The old guy’s eyes narrowed. “So you them, then? The ones asking about Scabby Moore’s? Pack of tourists if you ask me.”

Hawker wasn’t the only one bristling like an angry cat, so I stepped in. “Yes,” I said. “We’re tourists. We heard you had a unique offer?”

“There’s the—” one of the lads starts.

“Not a thing.” The old guy glared. “That’s what I came to say. The rumors about Scabby Moore smuggling moa are a load of hogwash. Besides, he’s long dead and his farmhouse is in ruins. Best thing you can do is look for your imaginary monsters elsewhere. And keep my grandsons out of it.”

This man knew something. Was he testing our resolve or warning us off his territory?

Arthur pulled a tenner. “I’m the kind of tourist that likes interesting things and can pay for them.”

The old geezer clinked the coins in his pocket and frowned. “You’d better leave,” he said.

“Was that old geezer threatening us?” Hawker demanded the second we were out the door.

“I don’t think so,” Jean said. “Moore’s house burned down around him in 1890, but he didn’t die until 1905. He was a nasty bugger and quite blind, even before the fire.”

“We have enough evidence to believe there might still be animals trapped somewhere,” Arthur said. “Also, there’s a story that Scabby shot a giant eagle, and Frederick Fuller aged the bones up for that scientist, Haast. It’s unlikely, but we might be onto something big.”

Hawker rolled his eyes. “Big? Giant birds? I can’t believe we’ve come all this way for giant birds.”

“Don’t mind Hawker,” I said. “Since we discovered taniwha are probably mythical, he’s done nothing but complain he missed out on the big Australian hunt.”

“Australia has cryptids I’ve always wanted to catch,” Hawker snapped. “And what are we looking for? Overgrown birds. They’re not even man-killers.”

“Hmmm,” Jean said, “I heard the Australian team weren’t doing so well.”

“If I’d been left in charge, we’d have the giant platypus by now,” grumbled Hawker. “What kind of idiot loses half their team to crocs?”

After giving up on the locals, we took the boat around to Waipara River. We were greeted by clouds of biting sandflies thick enough to eat. They tasted terrible.

We stayed the night at the Moore homestead. It was indeed a burned-out wreck, almost totally abandoned, but next morning we found a relatively fresh track leading further inland.

A kiwi blundered along the path, then blundered back, quick.

Hawker took the opportunity to say that giant kiwi were hardly quarry worthy of his expertise. I was about to say that moa and kiwi were very different creatures, when splashing and shouting interrupted me.

“Smugglers?” Pat mouthed.

Hawker shrugged his rifle onto his shoulder and we slipped closer to the river. Not that we needed to sneak. The two lads were too busy dunking each other and roaring with laughter to notice us.

“Well, it looks like there’s one advantage of working in New Zealand,” I said. “We can take a dip without being eaten. Not many trips where that’s been true.”

Pat slapped at the cloud of sand flies around his face. “Pretty sure I’m being eaten alive, right here. Ah—wait a minute, aren’t they the men from the pub?”

“Yup,” Hawker said, aiming his rifle aimed at the lads.

They finally saw us and scrambled out of the water in a mad dash to pull their clothes on.

One of the lads sighed. “I guess you got this far. We might find some eggs. Gramps shouldn’t be too mad.”

“We aren’t egg hunters, out for shiny baubles, either,” Hawker snapped. “We’re here to protect the last of the moa before they end up on some toff’s gold dinner-plate as a rare delicacy.”

“So, we’re close?” Arthur said.

The brothers exchanged glances. “Gramps won’t like it.”

“Gramps might like being rich and comfortable in his old age,” I said.

A voice came from behind us. “Gramps would rather live a little longer.”

It was the old guy from the pub.

Within minutes, it was clear they were trying to lead us in the wrong direction, but that only made Hawker more determined. He kept coming back to a short stretch of trail near a high cliff. The only feature was a huge tree stump coming out of the rocky face. I put my hand against it.

Clunk.

“Well, I’ll be—” It was a hinged door wide enough for three giants to walk abreast. What had looked like a cliff was actually a vast wall concealing a hidden valley of grey scree rocks and thick forest.

“Well, at least we don’t need to scale cliffs to reach this lost world,” Arthur muttered as we filed through to the hidden valley on the other side. Exchanging glances, the locals followed us in.

“Wow!” Pat said. The forest stretched all the way back to the distant mountains. “That Scabby fellow thought big.”

An angry weka ran at us through the undergrowth. It almost became dinner when Pat pulled out a spear.

“Wouldn’t if I were you,” one of the brothers said. “Weka are tougher than old shoes.”

The ground was scattered with bones. Moa bones. Were there any moa still living?

Jean’s eyes lit up like brandy fire. “Footprints! Look at those!”

They were big ones too, like giant three-pronged leaves pressed into the velvety moss.

Hawker pointed to a huge indentation. “Maybe there’s something here even more exciting than moa.”

The excitement was palpable.

We scrambled over a rocky outcrop, past some grey dinosaur-like lizards—no, not lizards—the creatures had no external ears. “Tuatara,” I yelled. “I thought they’d gone extinct on the mainland.”

“1850, if I’m not mistaken,” Jean said.

I nodded. She was remarkably well-informed. “I think I’ll take a few.”

“Don’t you dare!” Gramps said. “Moa are one thing, but don’t think about touching those taniwha—ah, tuatara. They’re tapu.”

As a man of science, I was determined to take some. Those tuatara were rare and Natural History Museums and discerning collectors of herpetofauna would want specimens. Besides, they wouldn’t be safe here forever. Sooner or later, rats and other imported predators would get them. So, when the others tramped on ahead, I nipped back.

The creatures looked up at me. Smoke wafted up. It smelled like earthy nutmeg. The next thing I remember, I’d completely forgotten about the tuatara and caught up to the others.

“There!” Pat whispered, pointing into the brush.

Arthur nodded. He pulled out his hunting net.

A speckled moa broke cover. It charged right at me like a ten-foot-tall rugby forward, but with a sharp beak and claws.

I gasped. A Dinornis robustus, the South Island giant moa. We’d found it!

“Move!” Hawker yelled, pulling out a lasso.

I swerved.

A giant foot lashed out, clawing my side. I rolled out of the way, dropping my case. Blood dripped down my side.

Jean and Arthur distracted the moa with their giant nets while I scrambled to my feet. Hawker was waving a stick to hold it back.

Surrounded, the bird was dangerous. It rumbled a deep throaty blast, ripping at Pat with its claws.

Pat ducked.

It slashed its beak at Hawker, sheering his rope in two.

Hawker jumped back. “Shite! That bird almost got my hand!”

The bird’s head swiveled back in my direction. A shiver ran down my spine.

It charged at me again.

I needed to cover its eyes. Birds always calm down when they can’t see—well almost always.

My jacket would do the trick. Nimbler than a matador, I pulled it off, dodged a blow from the creature’s foot, and flung the jacket over its head. It perched precariously over the creature’s head before I summoned the nerve to tie its arms around the bird’s neck and secure the makeshift blindfold.

“Fantastic!” Jean said, expertly harnessing the birds.

“Yes, indeed. Well done,” Arthur echoed, before rushing to shake my hand.

Pat grinned and pulled out his drawing supplies.

“It was just a bird.” Hawker shrugged, like the rare creature was barely worth the effort.

The locals weren’t celebrating either. “Pouakai,” they screamed as a dark shadow skidded overhead.

No, not a shadow. A giant eagle, larger than two bears, dropped from the sky like a shadow of death.

What was it aiming for?

Then, hidden amongst the bush, I saw a moa chick, almost as tall as a man. Jean and I ran to protect the creature.

The eagle swerved.

Talons large as chopping knives dug into Hawker’s back. He screamed as the giant bird flapped, lifting him out of reach.

Most of the party was still staring, slack-jawed, at the gigantic bird carrying away a grown man when Jean’s net snagged Hawker’s foot.

Arthur threw his net, too. “Hold on!” he yelled.

Hawker screamed louder than ever. Flesh tore—his arm was still in the talons of the giant eagle, while Hawker, silent at last, tumbled to the ground.

I rushed over, but it was too late. He was dead.

“Now, go home before things get worse,” the old geezer said with barely-contained anger.

“No!” Pat snapped back. “You think Hawker would want us to come back with him dead and only moa to show for it? We’ve seen a giant man-killing eagle and we’re going to catch it for him.”

We took turns to dig Hawker’s grave in the stony ground. Arthur said a few words, then Gramps said a few more.

Pat ignored him and took out his drawings. They reminded me of the tuatara I’d forgotten. I raced back and very carefully placed a couple into my bag, staying well clear of their smoky breath.

That evening, Arthur radioed in to the ship to ask for a cage for catching the Pouakai—the giant Haast eagle.

When night set in, I had trouble sleeping. Something was moving outside, crashing through the undergrowth.

Comments (0)

See all