Basir lightly touched the metal ring attached to a pin at the top of the crescent.

“That’s the part you pull,” he said solemnly. “Then…” he made a flowering gesture with his hands and mimicked the sound of an explosion.

“Everyone knows that, idiot,” Pratik said. In the light of the cartoon mouse, his ratlike features were made comical by his walleyes. Each eye looked as though it was trying not to acknowledge the other.

Sana flicked Pratik’s ear, making him jump. “This is a chaff-bang grenade,” her English was sharp and crisp, like folded foil. “It explodes like a normal grenade, but also throws up bits of aluminium and other stuff to mess with a drone’s radar.”

Azizul nodded. His brows creased, pinching the small white patches around his forehead. In Hindi, he said, “You remember Tanvi and her gang? They got caught by the Rust Dogs. She said they had a chaff-bang and the Dogs got blown to pieces. She said they made hundreds of rupees on the wreckage. Along with the rupees they got from the scavenge run.”

The children all looked at each other, excited. Shesh beamed a smile and his head rocked slightly from shoulder to shoulder, basking in the pleasure of having acquired such a valuable item.

“With this, the Dogs can’t stop us!” cried Pratik, in triumph. Basir had a huge grin that spread from oversized ear to oversized ear. He slapped Pratik on the back and they all laughed. After a meager meal, they readied gear for the evening’s promising scavenging run.

“I still think I should carry it,” said Pratik.

He walked at the front of the group, strutting backwards down the center of the dark road. Each of his eyes seemed to take in both sides of the muddy path at once.

There were multi-story shacks that lined the walls of the road in the outer ring of Sun City’s residential warrens. From each barren window came the sounds of televisions and the aroma of frying garlic and onion. It appeared to be supper time, for those who could afford it.

The group of scavenger orphans had ventured through almost two kilometers of slums and still hadn’t broken free of the densely packed lean-tos and tenement housing. No one paid them any attention. They were not the only unattended children running around out here, and everyone had their own business in the stifling air.

“Let it go,” Azizul the Map said, with a big sigh. There was a short silence, in which all they heard was the squelching of their bare feet through the stinking mud.

“Come on. I’m the general of our little army. I should carry the grenade,” Pratik said. He smiled and tugged at the straps of his sleeveless greying undershirt as though they were suspenders.

“Not so loud, idiot,” growled Sana. They passed a tiny jutting house, where there was an intense argument taking place in Urdu. A woman with a scarf over her head threw out dirty water in the path of the children, glanced right through them, then turned and resumed yelling at the man inside.

“We already agreed to let Sana carry it, Pratik. She’s the one that knows machines best. Let. It. Go.” said Shesh. After thirty minutes of this idiotic debate, he was reaching his limit of irritation.

Basir nodded; his ears seemed to flop their agreement.

“You’ll be sorry if the Dogs catch us up,” sniffed Pratik. He turned in a snit and shoved balled fists into the pockets of his brown trunks.

“Just shut up and walk,” said Sana. She tightened the rope she wore as a belt around her yellow shirt with the humping unicorns. From it hung another shirt that had been fashioned into a makeshift bag. The heavy looking lump inside it was the chaff-bang grenade. Shesh didn’t like how it kept slapping against Sana’s thigh, but she knew what she was doing.

They all wore thin ropes or extension cords for belts. Each had a couple of plastic bags with simple tools. They all had wire cutters, nicked from a market or picked up with extra money in previous months. Azizul even had a multitool that he’d gotten from his brother, before he’d disappeared two years ago. Shesh had never met Azizul’s brother, but knew no one else in the Map’s family had shared his condition.

The children also carried scraps of cloth or canvas that had been repurposed into slings for carrying salvage. It was extremely dangerous to hunt for derelict bits of technology in the old industrial outskirts of the city. If you didn’t have enough bags to bring the loot back in, the risk was never worth it.

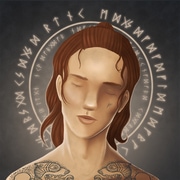

Shesh was pulled from his thoughts when Basir tugged at his stained tee-shirt. He turned and Basir pointed. Basir was the largest of them, and the oldest…maybe eleven or twelve years old. His silence and observant eyes made him an excellent look out. Shesh followed Basir’s finger. He could see the curving bases of massive smoke towers.

They could only see the bottoms of the cement cylinders, because they were on the ground floor of the slum city. Shesh knew the stacks were the second highest feature visible in Mumbai’s skyline and a critical landmark. The two smoke stacks marked the edge of Powai Lake industrial center. A little farther north, just past the stinking water refinery and desalination plant, the dense slum city broke. Once free of the slums, they could finally breathe a little fresh air.

Shesh, Sana, Pratik, Azizul, and Basir sat on the edge of a dam. All around the humid Duracrete facility, thick foliage grew. In the air, Shesh could pick up earthy sandalwood and the dank ivy scent of peepal trees.

The children’s slender brown legs hung over the precipice. They rested their chins on their arms, between the horizontal guard rails. The dam blocked a small river that fed into the big lakes northeast of Mumbai. The roar of the rushing brown water below them was deafening when they were down in the garbage-strewn ravine. From up here it sounded like the pink noise of a flat screen disconnected from the free network feed they called the Line.

The five of them sat looking at the orange light pollution. It filled the smog over the city with a warm glow. Jutting up above the slum skyline, like a rude finger gesture to the heavens, sat the smoke towers. Though, the smog spewing cylinders were massive and truly the largest buildings of their kind, they seemed to melt away in the glamour of Mumbai’s other great architectural feature.

Centered in the heart of the shanty town squalor, which grew around it like a tumor, it transcended the slums’ mass of multi-story shacks and corrugated aluminum palaces. The building loomed over the highest skyscrapers from the entirety of Indian history. It was where all roads in Southern Asia seemed to converge.

The Arcology stood without any contender as the largest building on this entire hemisphere.

The Mumbai Arcology glittered like a pyramid made of glowing diamonds and wore a crown of clouds well below its peak. The gigantic building was literally a self-contained city, sealed in Duracrete and carbon-glass. Hundreds of thousands of Asia’s richest families called the designer metropolis home. To the wealthy of the modern world, the contents of the Arcology were Mumbai. Everything else around it was merely living human shit.

Shesh wrinkled his nose at the gargantuan architectural marvel. To him, it just looked like a giant, radioactive dick. He remembered the info-screen of a decaying learning kiosk, outside the building he lived in when he was younger. It had said that the Arcology was over two kilometers tall. Its peak was higher than all of the nearby mountains. Its base was nearly a kilometer wide. They had gutted most of the old city to build it. There had even been a retainer wall to keep out the filth, but the slums just poured back in. They crashed at its impenetrable glass and steel foot, like a breaking wave, but were unable to seep in.

“I heard they have special elevator cars that run up and down and sideways,” Sana said, interrupting Shesh’s thoughts.

“I heard they have green food that grows in all of the walls,” Basir said. He popped the collar of his ratty black polo shirt. They had begun their favorite game. Shesh smiled.

“I heard…” Azizul the Map thought a moment. He scratched his chin, where brown islands floated in a pale ocean. “I heard that they grow their children in hydroponic vats!”

“Good one,” Sana said, with a laugh.

Not to be outdone, Pratik cleared his throat dramatically. “I heard that the Rust dogs grab scavengers to be ground up and fed to the Mumbaikars, with straws!” Everyone laughed. Pratik adjusted a nonexistent tie knot and grinned, his walleyes bulged with mirth.

Everyone looked at Shesh. He still stared at the skyline, absorbed in his musings on the accursed Arcology. Sana nudged him, bringing him back to the reality of their game. He glanced at her and she nodded expectantly. One eye bright with a rich brown iris, making its cloudy twin all the more lifeless.

“I,” said Shesh. “I heard that the Arcology is actually just a gigantic super computer. That all the people in the world have died and we are just a program it plays so it doesn’t feel lonely.” Shesh finished, with a whispery spooky voice.

“Woah,” Basir said. His eyes wide.

“Shesh wins,” said Sana, impressed. Pratik rolled his wide cast eyes and nudged Azizul, who rocked his head and made a funny face. Shesh’s white smile glowed in the darkness.

“Let’s get going, you lot,” chastised Pratik. They all rose and dusted off their frayed and rotting clothes, checked their gear, then stepped away from the guard rail.

One by one they squeezed through a hole rusted into a fence that spanned the entire north eastern outskirts of the city. A long band of red signage hung along it’s great length. Repeating along its entire length, in fading white text, a dozen different languages warned:

DANGER! Do not enter! DANGER!

Comments (2)

See all