- I’m beginning my analysis on the Byrnwood Library affair of the 2080s. The official report was pitifully sparse, but after digging into the case files for a while I eventually found reference to a hard copy journal. It had never been digitized before, for some reason, so I’ve taken the liberty of uploading its contents, along with some of my analyses.

The Journal of Julius Gordon

May 18th

I never thought I would be a writer. I never knew there was such a thing as writing. As a child bouncing along in caravans, scrubbing the mud for worms, listening to Grandfather’s songs in the hot dark of the firelight, I thought that words were only sound. I didn’t know they each had a shape, and that each shape was capable of infinite beautiful configurations. We all spoke the same sounds in those days, if we spoke at all. Our words, if transcribed, would have all shared the same shapes. I didn’t know that words expand when they take shape, they stretch and they play on the page. They take something from the writer and this thing transforms them into a Voice more singular than speech. Men and women can preserve themselves in words; they can become their Voice, larger and stronger than they ever were in life. The library has taught me this. Words die in the wind, but on the page they can live forever.

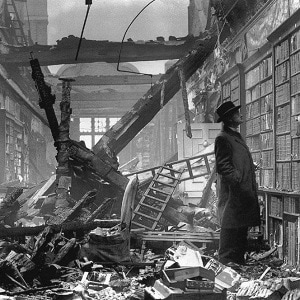

My Voice was inspired by the undying Voices before me. Surrounding me. I spent decades in the library before I ever considered the idea of putting my own Voice into shape. But at first, it was only a building to me. It was a refuge from the wild ones. I was barely a man then, a man with a handmade crossbow and his mother’s blood stained into his jacket. At the time, the library was only a refuge, but it was an ideal one. Three stories tall, with sturdy walls of stone and plaster. The stacks were a dark maze to hide in, and the park surrounding it was as fertile as any ground I’d seen on the island. There was a town here once, a small one. It was, and still is, called Byrnwood Village. The bombs never came here. Only the fallout, and the wild ones, and the storms. There are still hollow buildings all down the lane, picked clean and sagging in on themselves. According to the stains in the carpet and the bone pit in the park, the library was once home to a band of cannibals, but they either consumed themselves or moved on long before I arrived. Oddly, the library collection was barely touched. Perhaps the former occupants didn’t think to eat the books. Perhaps they didn’t even know what they were. I didn’t.

My curiosity taught me. As I made a home for myself, I studied the dusty flapping things on the shelves. I recognized some of the shapes from signs Grandfather showed me, and others I recognized from the sounds I already knew. It was slow going, but the town was empty and peaceful, and I was determined to understand this riddle of words. I started with picture books for children, dictionaries, and encyclopedias. The Bob Books were essential to my early education, as were the works of Dr. Seuss. It was four years before I could read and confidently understand my first novel – Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island. In that time, I’d had visitors. Several caravans passed through, families like mine. Wandering, looking for home and always settling for their next meal instead. I didn’t have much to offer them by way of either, but I did offer them entertainment. I read to them, usually out of the picture books, and I helped them forget about food and home for a little while. I gave them a window into a living world, where we could peer from our dead planet into a place too beautiful to mar with description.

As I learned the shapes of the words, I came to comprehend more and more Voices. Jules Verne, Iain Banks, Edgar Rice Burroughs, G.K. Chesterton, Asimov, Atwood, Ellison, and eventually the master of words and bright futures, Ray Bradbury. I believe I gravitated toward science fiction because it did not provide a window into a once-living world, a place inspiring painful nostalgia and violent envy, but rather it showed me possibility, a kind of hope that pumps the blood even when the heart begins to fail. As a side-effect of my education, I became a skilled storyteller, and I read to passing travelers from my ever-expanding repertoire of science fiction and adventure novels. Caravans would stay longer, and they would come back asking to continue the story. Sometime during the sixth year (I didn’t keep a calendar then) the Hanson clan asked if they could stay. I could not refuse. I had land, and they had hands to work it. With the safety promised by our numbers, more families accumulated over the years. By my estimate, we have eight families here today, and a handful of lone survivors. The library is large and it is generous. We are a community now, devoted to words and Voices. We are rarely threatened by wild ones, and if we are, our numbers and our ungainly assortment of weaponry have always repelled them.

Even so, I know we will not last forever. We are but flesh, and my flesh is growing old, aged beyond its years by radiation and malnutrition. I have solved the riddle of words, and I can now begin to transform the words into my undying Voice. For years I have dreamed of telling my story and joining the Voices on the shelves, but until now I have restrained myself. Until now I have not been worthy. When I am gone, this journal will live with others as the library has lived with us. It is the only thing I have worth giving to our dead world.

– I am impressed by this Julius Gordon. For a self-educated man, his journal is surprisingly erudite. His story of survival and emphasis on the preservation of knowledge reflect the ideals Minerva holds dear, leading me to wonder why this tale has been lost to obscurity. The many anthropological details of this band of survivors’ lives alone should have been enough to make this mandatory reading material. I shall have to investigate further.

Comments (0)

See all