The Sentinel’s scar over their chest remained the subject of their scrutiny for quite some time after they met the Sunfish. When they awoke long after taking the blow of the lance, addled and disconcerted, they were sure that the vision of their sun had been a dream.

The lance and their wound had been real enough, however; even though another sun had risen, their wound was evidence that they had seen and saved one the day before. It was a miracle they had survived at all. They remained near the shore of the lake from then on in case the mysterious hunter of the Sunfish came back to finish what they had started. Time passed, as it is wont to do, and more suns rose and fell over the horizon, but not into the lake.

They waited with the same lance that had almost struck the Sunfish close to their chest. They called it Thorn, and concluded that whoever this lance had come from was a Nettle clinging at the edge of their vision. They stayed alert, guarded, and prepared for the potential return of the Nettle. Sentinel became a name they earned with vigilance. And it was due to their vigilance that they caught a minute tendril of song years after their encounter with the Sunfish.

The Sentinel had stitched their small talons to one of their stong-hold nests around the skirt of the lake and was preparing to roost for the night with their lance tucked under their wing. Their cloak, the color of a midnight sky, was draped drowsily over their narrow shoulders. It was then they heard a coiled voice not unlike distant birdsong pirouette from the center of the water. They froze and listened. The voice itself sounded achingly familiar, but the melody shied from their ear.

The feathered grip on their Thorn tightened as they considered. Other birds were scarce and far between in the area. Furthermore, they clumped together, usually away from the odd, reclusive proclivities of the Sentinel. The anomalous notion of a lone bird in the middle of nowhere, so near the Sentinel’s charge, set their fears ablaze. Could the Nettle finally have returned? But, then, why would a hunter announce their presence so readily if they meant to startle their quarry, as had been the case so long ago?

All of these thoughts fluttered against their hammering ribs as they crept from their nest, Thorn poised at their scarred torso. Quietly, they raised the hood of their midnight cloak to obscure their face as they peeked from the leaf-bedecked limb of their tree and peered furtively at the lake.

There was nothing there to be seen. Not a ripple, wave, or beating of wings disturbed the placidity of the dusk. It was as if the environment itself was in a reverie, and the song had been the dream of a sleeping lake. The Sentinel lowered their head, chin tilted up, and waited for another swatch of song to twine through the air. The sky deepened. Thorn grew restless in their wing. They shifted uneasily.

Three notes of song lilted over the water, soft as candlelight, and the Sentinel sprang from their hiding place, Thorn raised. But still no sign of movement, other than their own, could be seen in the growing darkness. They narrowed their eyes, stupefied. The song continued, even farther away-sounding than it had before as they hovered above the lake’s shore.

“What’s going on?” they asked the evening air.

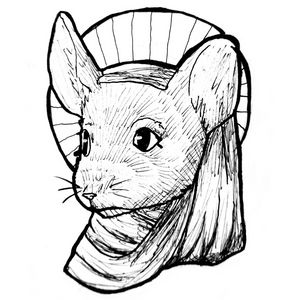

They fluttered to the shore, Thorn in tow, and landed at the soft crumbs of pebbles there. The pebbles shifted beneath the Sentinel as if the shore was sighing as the lake’s song spun around them. Within moments, however, a rustling like torn paper alerted them to the presence of someone moving behind them. They jerked around, tense and prepared to fight, lance raised. A small mouse draped in a pink headscarf was not what they expected to see.

The Sentinel didn’t lower Thorn as they studied the mouse. They had brown, slightly ruffled fur and scarred ears that flicked in the chill of the air. The dress they wore was a shade lighter than the blushed, rosy color of their headscarf, and their eyes sparked brightly with either quiet intelligence or mischief. Or both. They held themselves with a lithe kind of poise that didn’t quite match their homely garb.

They blinked at the Sentinel.

“That’s not a polite direction to point that,” they chided, gesturing at Thorn, round ears bouncing slightly. Their voice flickered in the Sentinel’s mind, stirring memory like silt in a river basin.

“Do I know you?” the Sentinel asked with more bravado than they felt, gaze hard. They were careful to hold Thorn without trembling.

“Not many live around here, Sentinel,” the mouse said. “Wouldn’t you remember me?”

It wasn’t an answer. The Sentinel tilted their head skeptically, but lowered their lance so the tip tickled a brown pebble at their feet. The mouse smiled and relaxed their brown shoulders.

“I appreciate the trust,” they said in a chipper tone. The words were almost spoken in tandem with the melody gently whisking the air. The Sentinel tutted lightly but didn’t say anything more.

“I suppose you want to know who I am,” said the mouse, gazing at the lake over their shoulder.

“Yes,” the Sentinel responded tentatively, adjusting their cloak so they could see the mouse better.

As some sort of response that definitely wasn’t an answer, the mouse made a pitying humming sound and stepped toward the lake. The Sentinel froze, then rested their beak on Thorn’s circular hilt, utterly lost as the mouse studied the lake sedulously. The mouse folded their small paws behind their back, then turned to the Sentinel so abruptly that they reeled slightly.

“You don’t usually hear that song this clearly,” the mouse said wonderingly, eyes sparkling as they stood on the tips of their paws. “Often, the melody is so far away. That fish has got quite some mettle to come this close to the surface.”

“Fish?” the Sentinel said, too incredulous to be terribly tactful. The mouse lowered themselves back down and smirked.

“You’ve never heard that song before, have you?” they asked, clearly not actually wanting an answer. They shifted back toward the water, bouncing on their narrow heels. “I suppose these overlarge ears have to have some benefit. Anyway,” they continued, side-eying the Sentinel surreptitiously, “you know the Sunfish, don’t you?”

The Sentinel had barely managed to compose themselves after the initial implication of a singing fish, but at the mouse’s words, they gasped outright, abandoning discretion altogether. They had grown so used to the idea of the Sunfish as a distant, almost mythic figure in their memory that someone else’s words about him played along their spine as if it were a xylophone. Their shock must have been quite comical judging from the mouse’s expression, but the Sentinel didn’t care. “That’s the Sunfish singing? How?”

The mouse dropped their gaze slightly. “Oh, yes, that’s the Sunfish alright.” They raised their chin, whiskers twitching like leaves. “He’s been able to sing ever since he tasted the blood of a bird. And that bird hasn’t since left, as I see.” They looked pointedly at the fold of the Sentinel’s cloak that hid their scar. The Sentinel’s guard snapped back up once more.

“How do you know all of that, eh?” they asked sharply. “I don’t know you, but you clearly know me.”

The mouse...giggled. The Sentinel shifted uncomfortably at the mouse’s reaction, bemused.

“I’m the one who treated your wound, Sentinel,” they said, the edge of their voice still lifted slightly with laughter. They sobered quickly, however, tone lowered as they continued. “I couldn’t let you bleed out. You were laying in the water when I found you — the cut was fresh. The Sunfish was still there, trying to do what he could for you, but I’m the only magician in the area.”

It made sense now. As the mouse spoke, splinters of memory dislodged in their mind and they could hear the lilting voice of the mouse before them, the flash of their pink headscarf, the touch of their paw pressing cloth against their chest. “Oh,” the Sentinel said, feeling abashed now. “I’m so sorry I didn’t remember you, I don’t know why—”

“Oh it’s fine, Sentinel, no reason to apologize.” The mouse gestured dismissively, waving away the Sentinel’s words as if they were flies buzzing around them. “I didn’t expect you to remember me; you were unconscious for most of it.” Their gaze pierced them then. “But I also didn’t expect you to stick around.”

“Yes, well,” the Sentinel said, lifting Thorn slightly and peering contemplatively at its honed edge, “whoever tried to kill the Sunfish is likely to come back sooner or later. And now I know it’s the Sunfish singing, the Nettle will likely find out too, and will be able to track him down.”

“The ‘Nettle?’” the mouse asked.

“That’s what I call the person who left this scar,” the Sentinel explained, gesturing to their chest.

“Hmm.” The mouse gazed down for a moment, seemingly lost in thought. The Sentinel didn’t know what to do, so they fiddled with Thorn and listened to the Sunfish’s distant song.

Finally, the mouse lifted their head to study the Sentinel. “Would you like to swim in the lake and warn the Sunfish about the Nettle?”

The Sentinel decided right then that all the words that sprang from this mouse’s lips were really just lined-up punches. They blinked and stared exasperatedly at the mouse, not bothering to ask for clarification. The latter clucked their tongue and reached in one of the pockets of their dress, rummaging for a moment.

“With magic, Sentinel, magic.” They removed their paw from their dress and extended it so the Sentinel could see a single brassy scale held in their palm, where it clasped the receding light between delicate ridges etched on its surface.

“Is that the Sunfish’s?” the Sentinel asked weakly, their grip on Thorn flexing unconsciously.

“Yes,” said the mouse, retracting the Sunfish’s scale and lifting it to their pointed face with both paws, “but it doesn’t really matter. I prophesied — it would do the job were it from any fish at all.” They closed their eyes, their lashes quivering like butterfly wings. The radiance on the scale swelled so that it engulfed the mouse’s nimble fingers like honey. “All that matters is what you do with it.”

The Sentinel watched as the scale erupted into dazzling, pulsing light. If they hadn’t been paying attention, they wouldn’t have been able to notice that the beating of the light matched the rhythm of the Sunfish’s melody. “There,” the mouse whispered. They sounded slightly strained. “Now you’ll be able to see in the darkness of the water.” The Sunfish’s voice behind the mouse carried out a piercing modulation, and the scale reached its peak brightness.

“What should I do with it?” the Sentinel asked.

The mouse opened their eyes. They extended their paws.

“Put it under your tongue, Sentinel,” the mouse responded, “and warn your charge.”

The Sentinel hesitated, staring at the scale in wonder as the stars beyond waltzed gently amid a wash of blue. The mouse waited for a moment, then said, “I know what I’m doing, you know. I didn’t heal that fatal wound of yours with just herbs.”

“No,” the Sentinel said quickly, “sorry, I mean, it’s just — what will I tell him? Does he remember me? Why would he believe what I have to say?”

“Well,” the mouse said, still holding the scale out to the Sentinel as the amber light stroked their face, “either you go, or you don’t. It’s up to you.” They waited a moment before stepping forward to place the scale carefully among the pebbles at the Sentinel’s talons. Then, without a backwards glance, they walked away, back toward the undergrowth of the shoreline.

“Uh, thank you?” the Sentinel called to their retreating back.

They watched the flick of their tail fade into the monotony of curling ferns, then peered at the Sunfish’s enchanted scale with a weak twitch of suspicion. They weren’t certain why the mouse would just show up and help them out like this, but then again, they had saved the Sentinel’s life years before. If the mouse had meant to assist the Sentinel, maybe they were right to give the Sentinel the means to speak with the Sunfish and warn him about his danger. The Sentinel didn’t have much to lose, anyway.

The Sentinel quietly set Thorn upon the pebbles and picked the glowing scale from the ground between their brown feathers.

This is what they had to do, they supposed. They opened their beak and, without further ado, dropped the scale under their tongue. They then snapped their mouth shut, closed their eyes, and dove, beak first, into the serenity of the lake.

Comments (0)

See all