When I was too old to go out, the responsibility fell to my sister, Harley. Because she wasn’t yet susceptible to the debilitating migraines that the rest of us suffered, it was she who took our mother’s grocery lists, she who ran the errands, she who rode her bike through the barren streets.

On her way back inside, she passed the empty stake in the grass and I saw her look at the slack and coiled leash tied to it.

“Here, grandpa,” Harley called and held out a little bag to the old man, who waved his hand to dismiss it.

My grandfather, to whom we needed to shout to be heard over the television now, hadn’t bothered with the earplugs they'd been handing out in little plastic bags from the back of a supply truck; he didn’t trust them.

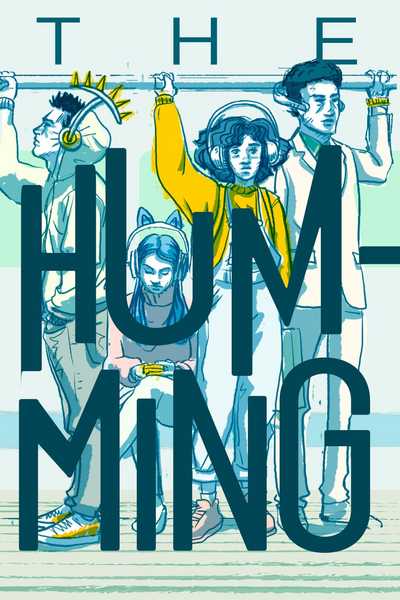

The supply envoy reminded me of when the ice cream truck came around, the way kids ran to catch it—and it was mostly kids; ever since The Humming got loud enough to hit the cities, the government had encouraged parents, and people old enough to be susceptible, to stay indoors until they could figure out whether or not it was harmful. At that time, it was not yet the unyielding thing it would grow to be and was more of an annoyance. Still, they had to take precautions. So, twice a month, from the back of a truck, two men parceled out earplugs like candy to trick-or-treaters.

After leaving our grandfather’s rejected pack on the coffee table, Harley came over to me.

I looked at the two sets of earplugs she'd handed me then back at her. “Harley—“

“What?” she said with a grin.

Every household was only allowed one pair of ear plugs every two weeks for every susceptible occupant and Harley knew this.

“I just asked them for an extra,” she said and shrugged.

Giving up, I could only roll my eyes half-heartedly and thank her.

In truth, I’d had a bad time the previous week when I’d misplaced my last pair. The headaches were bad enough, but sleep was next to impossible. Even with the earplugs it was difficult to block out the howling. Harley had known how stressful it had been for me and I couldn’t fault her for thinking of me.

I imagined how she must have asked one of the uniformed men for an extra pair, and how he must have first dutifully refused, citing that he had the rest of Squirrel Creek to get through. It probably only took one more look at the little girl with the bright, hopeful eyes before he was handing over the extra bag.

My sister was sweet like that. She always felt like she could count on people, and as a result, I think people truly wanted to do things for her. It was likely why my mom had kept Benjamin Bones around, even after he went crazy. No one could bear to break Harley’s heart.

Tier Two is marked as the stage when domestic animals went from restless to frantic and, in some cases, violent. They scratched at doors and butted against windows. When they were let out, they choked themselves on leashes. Well-trained and mild-mannered dogs leaped from moving cars at the first opportunity.

My mother, who had always disproved of the neighbors for discarding their dogs to their forgotten and overgrown yards, had since sequestered our own Mr. Benjamin Bones to a stake in the front lawn where for months he howled into the night and all through the day.

In my bedroom at the head of the house, I heard his cries the loudest and had grown to resent him. Meanwhile, Harley went out every day to try to draw out the dog she once knew and was convinced was still there somewhere beneath the fretful, jittery shell. She used treats and toys and an ever-patient tone. But each attempt at contact went ignored as Benjamin Bones only keened idly and paced within the shallow area around his stake.

I could see how deeply it bothered Harley, seeing him like that. She couldn’t possibly understand it. In her life, she’d known so much kindness that it hadn’t occurred to her that someone could be a lost cause.

It was the week I’d lost my earplugs that I snuck out in the night and wrest the collar from Benjamin Bone's head as he bucked and twisted in my arms. I watched him sprint off down the road, and I felt only relief.

The next day, when Harley went out with a bowl of food and found only a vacant leash, she ran back inside bawling. We reported him to the humane society and they let us know they’d keep us posted.

With my new earplugs, I helped my sister put up lost-dog flyers around town. But they only melted into dozens of others on the posts that were piling and pining for attention.

“Where do you think they go?” Harley asked, eyeing the many other lost faces, some familiar.

Along our street, many dogs had vanished over the last few years, and largely in the last few months. After Benjamin Bones, I wondered sometimes if others had gotten fed up in the night as I had. But then I remembered the sight of his form bolting away down the street that night, flitting in and out of sight in the shadows of the trees, how he hadn’t once hesitated or paused to think back, before finally and permanently blinking out of sight.

“I don’t know,” I said at last. “Maybe someplace better.”

Harley didn’t look satisfied but we moved on to find more posts.

For a long time after Benjamin Bones was gone, Harley was sad. I told myself she would get better, that what I’d done that night in my restless frustration was for both of us. She couldn’t go on thinking that the Benjamin we once knew would ever come back. I know now that I was selfish. If I’d just been more patient, we could have hung on a little while longer while the technology developed. They might have been able to reverse it, and Benjamin Bones and Harley would have been fine.

Although we didn’t know then where all the dogs went, it would only be a few months before they began chipping on a wide scale.

By the time Tier Three came around, enough cats and dogs had vanished that they started tracking them. They found that all the routes lead out of town and into the woods before their chips all blinked out of range.

It was there too, in a field just outside of our town and along the edges of the woods where, months later, Harley was found.

Comments (0)

See all