I shot out the door and, within five minutes, dashed past the boarding house where my best friend, Jayce, lived. I considered visiting, but knowing Jayce, it wouldn’t help solve my problem. Jayce, the Comrade in Arms? Amazing! Jayce, the Fount of Knowledge? Not so much. Today he was just Jayce, the Excuse to Get Out the Door. What I needed was advice, and that waited three miles away, deep in the heart of Gyra.

We lived in a forested area at the edge of Gyra city, far from respectable people. Mum made enough money that we could have lived elsewhere, and at times I wondered why we didn’t. My younger siblings had to walk over a mile to get to a school. And farmers and foresters didn’t tend to make for high-paying customers at the apothecary. But the inner city unnerved my parents. People there put on airs, trying to imitate the Old World without really understanding it.

“It’s weird,” Dad said one winter evening, our family huddled inside against the snow, with nothing to do but ask our parents questions. “You visit some fancy council member’s house and he’ll have a tractor engine displayed in his front hall. Like it’s some ancient work of art.”

Even Mom nodded. “It’s true. And meanwhile, the council keeps using marble chamber pots because they can’t agree if that “sewer system” idea sounds reasonable or not. It’s insane.” She drummed her fingers against a steaming mug of tea. “You get this sense of vertigo. Like you’re looking at the past and the future at the same time. Better to stay outside of it.”

“Firmly in the past.” Dad gave a wry smile and shoved another log onto the fire.

Still, from my vantage point, the city seemed plenty sophisticated. There were painted buildings and market stalls selling strings of pearls, shipped all the way from the outer islands. Merchants trundled by in wagons loaded with cheese and councilmen paid to be driven around in carriages draped with embroidered cloth canopies. It wasn’t the life I wanted, but I could see why people aspired to it.

At the center of the city waited the Basilica of Cia, my destination. Very few buildings in Gyra were made from stone, but for Cia, people made exceptions. Limestone walls sparkled beneath the sun. A pair of Mediates guarded the front gate, their blue robes growing gray from the dusty street. I gave a bow to each as they displayed their open palms in greeting.

Inside the main courtyard, scenes of the spirits back when they roamed the islands lined the walls. A few I recognized from stories my teachers taught in school – Atule blessing the birds with song. Ohi taking the form of a seal. But the frescos stretched from floor to ceiling and most I knew nothing about. Being Displaced, Mom and Dad never preached Gyran religion.

At the center of the nave stood a statue of Cia, Queen of the Spirits. She extended her hands palm first, like her disciples, and beneath her rested gifts devotees had brought from the forest, like clusters of pine cones and a hollow snake skin. As usual, my gaze lingered on Cia’s blindfold. According to the stories, the rifts took her eyes. Yanked them right out of her head. Every morning a Mediate tied a fresh cloth over her face. They said that one day, the statue would open her marble lids and they would leave it uncovered, new eyes gazing back at them. That would be the sign of Cia’s return.

Mom liked to mutter at superstitious tales like that. But I never could be sure if it sounded silly or beautiful. I still got the shivers standing there, imagining she could see me through the stone and fabric. I stuck out my tongue to break the illusion and then hurried to the east wing, straight for the music conservatory.

I arrived to find Ali inside, wiping a cloth over the bow of her violin. A pair of older musicians chatted at the other end of the room, but otherwise she was alone. She always stayed late after work to fit in more practice. Ali played in the orchestra that greeted the sunrise with Cia each morning. Music from dawn to noon. Our family never prayed to the spirits, but Ali was willing to take any job that let her play music and they were eager to have her. Old World instruments were rare and no one yet could replicate the craftsmanship of Ali’s violin.

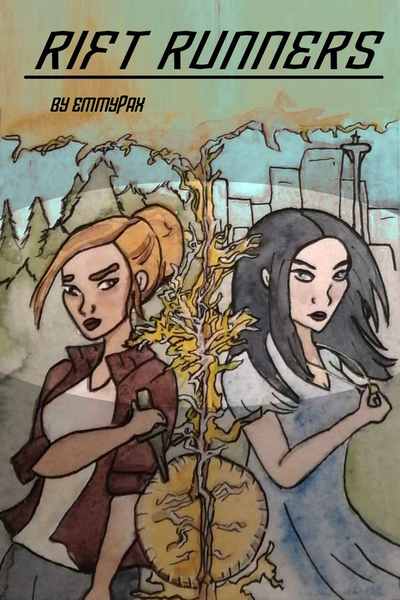

At my approach, huffing and puffing and smelling like a work horse, her eyes lifted. I always thought I must have been made of the left over parts of Mom and Dad that my older sister rejected. Ali took Dad’s blue eyes, pale skin and rigid posture. Like Mom, she had dark hair, but Ali’s hung straight. I think it knew she’d give it a stern lecture if it didn’t fall in line. Then there was me – dirty blonde hair I tied in a knot without brushing and brown, sun beaten skin.

With her music and model citizen behavior, if any of us had a chance of cracking into the upper classes, it was Ali. She even spoke like a proper Gyran, rather than mimicking our parents or the roughs Dad worked with. It would be an accomplishment for a child of two Displaced. People born in the Old World, like our parents, rarely shook that label. To the city council, they were outsiders, filled with suspect ideas from a failed civilization; remnants from a world the spirits abandoned, doomed to be sucked away by the rifts.

Ali slid her violin inside its case, her lips puckering at my unexpected approach. “Did you walk here?”

“Ran.” I grinned at her obvious discomfort and tapped one of my boots against the polished stone floor so she could see the dust drift off.

“What was so important you couldn’t wait for me at home?” She snapped the case closed.

We left the conservatory together, nodding to the Mediates and musicians. “Dad backed out of another expedition,” I whispered.

Ali’s jaw clenched. “How brilliant. What else?”

“Mom said – well, it might be good news.” Part of me wanted to believe it was, but Ali raised her eyebrows. “Judd asked if I could take Dad’s spot. Mom told him I could.”

“What?” Ali’s eyes widened.

“It makes some sense. She said she’s worried Judd might fire Dad.”

“I don’t believe it. She’d go herself rather than send you. You can grind up Dad’s medicine and run the front shop. She must be hiding something.”

“You think so?” I sighed as we stepped to the open street. I’d expected her to say as much, but couldn’t help feeling disappointed. “She might be trying to make up for how awful the last few weeks have been.”

“No, she wants you out of the house. Cleo and Kenny are in school all day. I’m at orchestra. She’s getting you out of the way.” Ali’s tone was definitive. No sense arguing. Ali had that kind of magical affect on people, especially me. When she said something, you listened and you believed her.

“Well, whatever is wrong, she won’t talk about it.” I ducked out of the way of a wagon rumbling towards the Bascillica gate, my mind distracted. What exactly was I even worrying about? Dad was already sick. What else could go wrong? “So… maybe there’s no point in-”

“Not even when she thinks you can’t hear? You haven’t tried hiding by their window yet?” Ali shook her head, a half grin playing at her lips.

I grunted a laugh. “What is this? An opening for a lecture? Fine, I tried, but they shuttered it. Then Mom said Dad was sleeping, but...” My emotions came in strange spurts these days and I had to blink to keep from crying. Dad fell sick nearly a month ago, but we’d thought he’d turned the corner, only for him to relapse. And now Mom was worried enough to lie to me.

Ali touched my shoulder. She never made grand displays of affection, but her small gestures held tenderness that made up for their infrequency. “You’re really worried, aren’t you?”

“I leave for Paumee tomorrow. Tonight is my only chance to figure this out.” And that was it right there that was killing me. All of a sudden I would be gone. A week away without knowing what was happening to Dad and how bad things might be.

Ali nodded, her face grim. “The window hinges on the exterior of the house. If you boost me up, I can pull out the pin and it should swing open from the side.”

It wasn’t often she helped me break rules. Forgetting myself, I tried to hug her. “Oh Ali-”

But she fended my arms away. “Now, there’s no need for extravagance.”

I laughed outright and feigned a curtsey back. “Oh no, of course not.”

“Stop it,” she said, but she was fighting a smile.

She waved down a carriage and I climbed in after her, glad her job afforded a few luxuries like this. Ali ran like a wounded badger and we needed to get home quick if we wanted to put our plan into action. Once our younger siblings arrived home, Mom wasn’t likely to hold incriminating conversations with Dad by the bedroom window.

“So remove the pin. How’d you think of that?” I gripped the rail as we lurched forward.

Ali stared at the violin case in her lap. I tapped my foot against hers and she finally answered. “I thought of it years ago. I think that’s how someone would break into the house if they wanted to rob us.”

I snorted. “Why would anyone rob us?”

“Mom’s medicine stash. That would fetch a decent price.”

“Balt it, you’re probably right,” I laughed, amazed at the idea. “I can’t believe you thought this through.” The image of my prudish older sister lying awake, worrying about some crook opening the windows and raiding the cellar, both surprised me and yet was so typical of Ali. Making this whole thing more ridiculous, her cheeks flushed pink with embarrassment.

Comments (0)

See all