I glanced at my sister as she slid next to me on the bench. Ali wasn’t crying any more, a mask of serenity aside from her pinched lips. Dad looked exhausted, dressed in a rough robe and with his blonde hair sticking up at odd angles. He heaved a shaky sigh as he took his seat. We waited for him to catch his breath, the fire popping in the grate beside us.

“It comes in waves,” he said finally. “A week or so from now, I might be fine. That’s what it was like for Marty.”

“Who?” I asked.

“Martin Fisher. He worked for Judd back when you were both babies,” said Dad.

“I remember him,” said Ali. “Red hair and beard?”

“That’s right.” Dad ran his hand along the grain of the table. “He’s the only other Displaced Judd ever hired. We used to go out for drinks together and... reminisce.”

“About... the Old World?” I said softly.

“Yeah, Marty never lived inside the Barrier, but he still... I don’t know. Had a piece of home in him?” Ali and I both nodded at Dad’s words. We didn’t know much about the Barrier, only that the Old World built it to keep the rift storms back. Anybody outside lived at risk of a rift sucking them away. “So Marty got sick,” said Dad. “He’d have a bad cough one week and then be on the mend the next. Then one day he found an ugly wound on his chest.”

He hesitated for a second before pushing open his robe. A damp cloth lay applied to his chest and he carefully lifted it, revealing a bloody stain. A narrow slash, about the length of my thumb, ran down Dad’s sternum, like a dagger had been flicked across his center. It glistened wet and sticky for a second before he replaced the cloth overtop.

“He asked your Mom to treat it. She did her best, but a week later, it grew larger.” Dad shook his head. “He started blathering about it being the mark and how it could kill him and...”

“You talked him into showing someone on the council, didn’t you?” said Ali, when Dad’s explanation dropped off.

Dad wouldn’t meet her eye. “It’s what we’d been trained to do. Laugh at it. Tell him to go to a healer and stop worrying. We all thought ourselves pretty clever when he came back with a new ointment for the sore. Then a week later, his wife came home from the market to a house crawling with Mediates casting purification charms. They told her someone heard Marty screaming and he’d been carried to the Basilica hospital. She never saw him again. Not even when they buried the body. They told her it was too contagious to open the coffin. Cause of death, pneumonia.” Dad smiled wanly.

I gripped the edge of the bench, trying to piece together what it all meant. “But – does that at least mean it might not be deadly? If no one saw him die?”

But Dad reached across the table to place a hand on my shoulder. “Marty’s not alone. I started asking questions, real questions, after he died. Some Displaced make it a year or more without anyone finding out. By then, they’ve got a massive, blood soaked hole in their chest. They’re too weak to walk. Too weak to get away when the council comes for them. If the council doesn’t kill them, they can’t have much time.”

“Displaced,” said Ali. “What have the Displaced got to do with it?”

Dad laughed, the sun playing over the depths of his cheeks so he looked like a grinning corpse. “I dunno, sweetie. But we’re the only ones who die this way. The good news is-”

“This isn’t fair!” I blinked through tears.

“The good news,” Dad repeated, “is that no one has seen their children develop the mark. It’s not hereditary. The rumor mill figures it’s tied to travelling through the rifts.”

“Oh, great. Now they cause disease too.” I pushed back from the bench, nearly unseating Ali on the other end.

“Shasta.” She gripped the table to steady herself. “It makes sense. You know what the Mediate’s believe. Feizi caused the rifts, so if the mark is named after him...”

“No, this is balted insane! We’re miles from the rifts! They shouldn’t be able to do anything here!”

“Sweetheart, don’t kick – all right, never mind,” said Dad as I sent the coal scuttle flying with my boot.

I pressed my hands over my ears and squeezed my eyes shut. Maybe this was the lie. Feizi’s mark didn’t exist. The council might be a bunch of balted idiots, but they couldn’t believe in childhood horror stories. But the look on Dad’s face when Ali accused him of sending Marty Fisher to his death haunted me. He was a good liar, but he wasn’t that good.

“So what now?” asked Ali.

“We go on as long as we can,” said Dad. “Keep the wound clean and uninfected. We’re lucky your mom’s a healer.”

“Healers don’t know a thing about the rifts.” I sniffed, surprised at how my nose and eyes welled up. “I’m getting water. Mom will want to change your bandages when she gets home.”

As I marched for the door, I could hear Ali still probing Dad for information. “What about in the Old World? Did you hear much about the disease there?”

I slammed the door behind me, too angry to be curious. I worked the pump until the water gushed like a frothing river, finally dipping my head right under it. But nothing could calm my speeding heart. Dad. Dad dying of some mystery disease so terrible, children joked about it.

The pump ran until it over filled the bucket several times. I sat with my back against the hard cylinder, my breeches soaking in cold water. My eyes closed to keep from crying. I wouldn’t have believed it at all, except that my parents did. And it had come from the rifts. Who was I to try to explain the rifts or how they worked? They were everything I didn’t understand about the world rolled into one.

What about the Old World? Did you hear much about the disease there?

Of course! If this was tied to the rifts, maybe they knew something in the world where the rifts started. I thought of my trip with the expedition party tomorrow. Maybe I didn’t need to give up on Dad yet. The rifts were the only gateway back to the Old World. What better place to look for a cure than in the world that had invented barriers that could repel rift storms?

The thought made me hopeful enough to smile. They had scientists and doctors in the Old World, not just healers like Mom. And with the rift problem so bad there, they had to be working on a cure. I’d watched people barter for years with Mom to get their hands on her medicines. I could do the same there – find something valuable and then swap it for whatever would save Dad’s life. Or I could steal the cure. I wasn’t above doing that.

But there was the question of how anyone could get there safely. The rifts would be a million times more likely to tear my body to bits rather than spitting me out near a cure, but it was so, so tempting to wish for it.

I pressed my head between my knees, shivering from the cold water around me and thinking of nothing but the Old World. Dad might not have toed the line on profanity, but he was much more reserved when it came to speaking of his childhood home. It wasn’t as though the name was banned. It even turned up in history lectures at school, but in our house, that name had a kind of reverence to it. The Displaced had known it by a strange word; one I could never place the origin of.

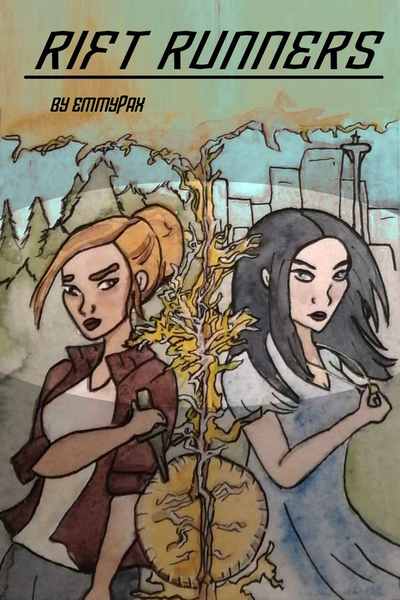

I drew my fingers through the pump water, wondering if some power greater than the spirits waited there. Something so powerful, it could even save my father. I tried to picture the city my parents had described to me; the massive mountains, the long coastline, the building shaped like a needle.

I said aloud that strange, mystical name the Old World went by. “Seattle.”

Comments (0)

See all