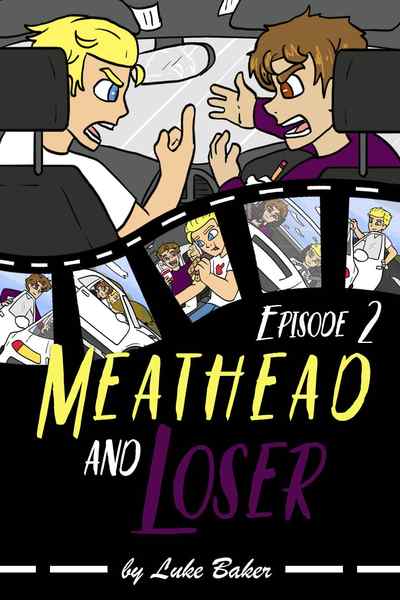

He had called me Dad. Tom’s son called me Dad. It happened more than once that day, and I let it. What was I supposed to have him call me? Uncle? Brother? Friend?

“It’s cute. It’s a good thing,” Tom said.

It was later that night, after everyone had made it home. Malcolm was with his mother, and I was with my boyfriend. Tom took a shower while I sat on the toilet, telling him about my day.

“But I’m not his dad,” I argued.

“Honestly, isn’t this easier,” he said.

His voice was muffled by running water and the shower curtain between us.

“How is this easier?” I said, standing up and pulling back the curtain.

He didn’t even flinch.

“Now we don’t have to explain that he has two dads; he already knows. He’s figuring it out for himself,” he explained and turned off the water to get out.

With a sigh, I handed him a towel and tried to say, “But you’re his dad,” still, he interrupted me at the end of my thought.

“Can’t we both be?” Tom suggested.

He had a new scar on his right arm, probably from reaching over the fryers again. In any case, Tom didn’t have that exhausted look of lifelessness he used to after work. Had he been tired like the old days, I might have helped him more. Instead, I left the bathroom to head back into our bedroom.

He followed.

I could hear his wet footsteps behind me until we were back on the carpet.

“Nick, I don’t know what I’m doing, but this should be good news. He likes you. We want him to like you. We want him to like us both,” Meathead went on.

“He shouldn’t call me dad; it’ll only confuse him when you tell him who you are. And you have to tell him. This isn’t the sort of thing you leave unsaid, like when you talk about me with your dad. Malcolm is a kid. Even if he knows something, he won’t understand it,” I argued.

Tom didn’t get it; he didn’t want to. I’ll admit, maybe he was on to something. He might have been right. Perhaps it was better that Malcolm had already seen me in a good light, but I couldn’t be sure. We couldn’t be sure.

I had to speak to someone I knew would be objective. Lucky for me, I knew just the woman. Erma.

I’d been seeing her regularly for a few months before the move. After the move, I hadn’t seen her in a while. I thought it was a good time for a visit. Of course, Tom didn’t argue against the idea, but I knew he’d have an issue. After all, how could I tell my boyfriend I needed to get back to therapy without him immediately thinking there was a problem?

“I’ve always wanted kids, sure. But everyone doesn’t get what they want. I’m not right for kids,” I said.

That office was always the same. Same uncomfortable seats, bright lights, and annoying woman jotting down notes in a notebook. The only thing different was me.

“Tom might have been a dick in high school, but I got into trouble too,” I added before Erma asked, “What kind of trouble?”

“I wouldn’t dissect a frog in biology class. Didn’t want anyone else to either, so I... set them free,” I said with a soft chuckle at the memory playing in my head.

“You set them free?” She asked.

“While everyone was having lunch, I broke into the school lab and tossed frogs out the window.”

She laughed behind her notebook. I guess we had known one another long enough to laugh at each other. And it was funny. In hindsight, I probably killed more frogs than my biology class.

“I’m a bad influence... I’m gay. What kid wants to grow up with a gay dad, with gay dads? It’s like asking to be bullied,” I explained while fidgeting in my seat.

How had she not changed that room? I was sure her other clients must have hated it just as much as I did.

“But you’re comfortable with your sexuality, aren’t you?” She asked.

“I am, but kids don’t have a choice who their parents are. Even if he likes me, other people won’t. They’ll hate him by association.”

The way light reflected into my eyes when I looked at her face made me feel I was looking at God. Not because she was all mighty, but because I couldn’t see her eyes. I couldn’t see her eyes, but I needed to know she, if no one else, had the answers I needed.

As usual, Erma gave me a lecture that amounted to little more than telling me I had control over my life. It felt hollow at times, but sometimes it helped. She told me to think of what was best for Malcolm before worrying about “the outside.” I thought worrying about “the outside” was the best way to protect him. I wasn’t even the kid’s father. Should I have had so much influence over him?

It was dangerous to get close.

Comments (1)

See all