No matter how he busied himself, the encounter with the illusionist called Emre stayed fresh in Osmund’s mind. His mood remained low the next day. Somehow, not getting laid had been the least of his problems.

He wasn’t even my type, he lamented. If I’d just been a little more choosey, none of this would’ve happened! Then again, Emre had said he’d been waiting for an opportunity to get him alone. Perhaps this meeting was inevitable. But why, oh why did it have to happen after he had his hands down my pants? he thought sourly. Or my towel, that is…

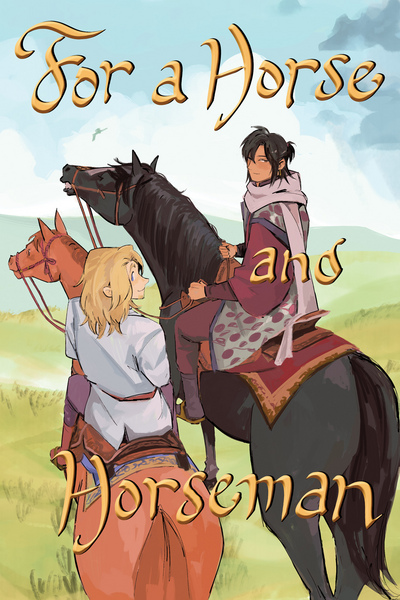

The whole mess was none of Osmund’s business. He repeated it to himself like it was an important one of his old lessons, even as he saddled up Banu for a ride at the end of his workday. Thankfully, one happy neigh from the good-natured horse chased his stormy thoughts away.

“Are you ready, princess?” he cooed, affectionate with gratitude. Banu matched his enthusiasm tenfold, practically prancing in place as Osmund climbed onto her back. “Time to run!”

Banu might not have turned heads like Anaya could, but only a novice horseman would overlook her. The chestnut horse was dependable, and she was swift. They began their gallop down the wide road that opened up into the rolling hills, and Osmund could’ve been soaring.

He’d forgotten, somehow. After all those many months destitute and alone, he’d forgotten the sheer joy of the saddle. Likely he’d never see Bella or Minerva or Callista again, and though his heart would always be heavy with it, his delight in riding hadn’t died with their loss. In spite of everything, he couldn’t have fought off the uncontrollable smile if he’d tried. Craning back his neck, he hollered into the wind.

Besides being a fine horse, Banu was as good a companion as any could hope for. She took commands readily and was eager to please. Osmund directed her towards long, easy stretches of grass where he’d be sure to spot any obstacle, and so he wouldn’t lose his way if the sunset caught up to them too quickly. The last thing he wanted was to be guiding her through unfamiliar territory in the dark.

They rode and rode and rode, until Şebyan was no more, replaced by grassy knolls dotted with specks of color. The world flew by, brilliant and bright: the pinks and blues of wildflowers, the unfurled arms of wild olive trees. Osmund felt light as a feather. It was just him and Banu and no one else, not a care in the world. The clouds hung low, and the hills below seemed to ask for rain. Not even getting drenched would bother Osmund now. This was all life was. Better than a warm bed, than a hot bath, better still than random encounters with men—the good kind, at that.

He closed his eyes and felt the air on his face. Valcrest seemed infinitely far away. The Empire could be home, he felt. As long as he had this.

They arrived back at the stables just before the downpour started, which was completely unlike Osmund’s usual luck. Perhaps his fortunes were changing after all.

He made sure Banu and the other horses were cozy and warm with no leaks in their pens to trouble them (Anaya snorted at him contemptuously, as if he’d personally ruined the weather) before he headed into the house, hoping to make it in time for dinner with the others. He was falling into routine here, he realized happily.

But for the second time in as many days, a feeling of something off welled up inside. Barely a couple steps through the door and Nuray scurried past, looking shaken, a pitcher of something grasped firmly in both hands. She didn’t even seem to mark his presence.

Osmund watched her go, bewildered. Then he saw the other servants standing in the hall, uncharacteristically still, as if huddled in waiting for some terrible event to pass. He was at a loss. It was well after the workday, and only a few of the government workers remained. No one stayed at the house full-time except some of the servants, and Şehzade Cemil himself.

Cemil. His personal bedroom was somewhere in this grand house. Not being a domestic, Osmund didn’t know exactly where, and he scarcely dared wonder. But the uneasy feeling in his stomach twisted further when Nuray returned, her brown skin almost ashen with stress.

“It’s bad today,” she told the others. She looked ready to cry, Osmund noted with astonishment. “There’s no helping him.”

“Who?” he blurted, though as every eye fell upon him, he suspected he knew.

After all, who else could she mean?

He saw their eyes flicking back and forth, silent deliberations happening in front of him. The feeling of being an outsider was back in force. They still don’t trust me. I’m not one of them. I don’t belong here.

“The şehzade,” Nuray sniffled, breaking the wall of silence. “He’s not well.”

“He’s sick?!” Cemil had always seemed the model of perfect health. “What happened?!”

They all exchanged another glance. “Headaches,” one older gentleman explained. He was a clerk of some kind who Osmund often saw making marks on parchment as he inspected the larder. He tapped his forehead, perhaps not expecting the Tolmishman to understand him. “Very very bad.”

Headaches? Osmund furrowed his brow. “Is there not medicine? W-what have you tried?”

A woman—possibly the pharmacist—started rattling off a list for him. Osmund was quickly overwhelmed; he didn’t recognize any of the Meskato words, no doubt various names for plants, trees, and herbs. “May I see?” he interjected. “I-I’m sorry.”

Nuray tapped his arm, assuming the role of his handler. “Come on. I’ll show you.”

She guided him to an open room facing the rainy courtyard, which seemed to be where the pharmacist prepared her tinctures. (The others trailed behind; they must be desperate indeed if they were hanging their hopes on a stablehand.) Osmund scanned the little containers, in which he spotted linden, jasmine, and what looked like violets. There were also tools that might be used for administration of the cures produced here.

“Nothing has worked, and now he refuses everything but simple tea,” Nuray cried in frustration. “What do we do when our prince is in so much pain?”

This little pharmacy was well-stocked indeed. It was hard to imagine they lacked for anything here. Even the head physician in Valcrest Castle, who hated with zealous nationalism all things un-Tolmish, wouldn’t be able to marshal a word of complaint.

Look closely, Osmund told himself, focusing with all his might. Isn’t there something missing? Something not found in the average book?

Without another word, he sprinted right back out into the rain, leaving the assembled servants behind. Doubtless they were all staring after him, jaws agape, thinking they’d been wrong to trust this foreign madman.

And maybe they were right!

Osmund made a beeline for the courtyard and its gardens, where he’d recognized some of the plants on his first day here. It was a lovely sight in the evening rain, but there was no time for that.

He kneeled in the dirt (soaking and sullying his clothing after all), and examined the rows of blooms bowing their heads to the tap, taps of the heavy raindrops. He was sure he’d seen it, it had to still be here…

“What are you doing?!” he heard behind—Nuray’s voice. She was going to be as drenched as he was. “These are the şehzade’s gardens! Are you mad?! You’ll be ████ for this!”

She snatched for his arm again and tried to peel him away, but Osmund shook her off, unable to afford the distraction. (Distantly, he hoped very much the word he hadn’t understood meant something like “lightly reprimanded”.) “I’m going to try something!” he exclaimed. “It might help!” She didn’t stop him after that, even when he dug the beautiful flowers, roots and all, straight out of the earth.

Osmund made his way to the kitchens, where he pantomimed a mortar and pestle until they ended up in his hands. The servants stood back and watched, likely with the fascination of seeing a condemned man seal his fate. If this didn’t work, Osmund thought glumly as he beat the plant matter into mush, he was going to be lightly reprimanded at the very least.

“That isn’t tea,” Nuray pointed out, not sounding critical so much as hopelessly confused. “Our medicines have had no effect.”

“I know,” Osmund assured her without taking his eyes off the work. “I-I really need to do it the way I’m used to. And I don’t know if it would serve as a tea, anyways.”

She looked at him for a long moment. “I hope you know what you’re doing,” she said at last.

On one level, mechanically, Osmund did. He’d done this very thing many times before.

And on another level—the level concerned with his own survival and with keeping his head down—he really, really didn’t!

![[Ch8] Evening Rain](https://us-a.tapas.io/sa/5a/d8acca11-745d-4d94-881a-4157b46c85dc.jpg)

Comments (9)

See all