"Well, okay." Nina's parents were remarkably lenient with her, for Russian parents. Her classmate Yulia's mom barely let her do anything when she was still at home, so she went to college in California and then straight to teaching English in Thailand after graduation, where, according to her Instagram, she was going clubbing on beautiful tropical beaches every night. Yulia's mom still sometimes called Olga to complain her daughter never visited. Nina's mother just made sympathetic noises and said things like "she'll miss you eventually, I'm sure." She never asked Nina too many questions about Nina's friends or activities, trusting her to come to her parents if she needed them. And Nina's father was the same.

All that being said, Nina wasn't sure if homosexuality was the limit of their tolerance. She managed to get them to understand Cory went by Cory now, but gender neutral pronouns weren't really a thing in Russian either. There was no concept of singular they in Russian, her dad explained, several times.

And now they would both be out of the house when Nina needed it.

"Tea should be ready by now," her dad said suddenly, then called, "Olya! Tea!"

Nina's mom appeared from wherever she'd been reading on her phone— the study, probably— and said, "are we having a little tea party here?" She moved past Nina to the cabinets. "I think we still have some of that wafer cake from the Russian store..."

When people saw Nina next to one of her parents, they noted the profound resemblance. When they saw her with both at once, they were surprised at how much she looked like a perfect average of her mother and father: her dad's dark frizzy hair and Ashkenazi nose with her mom's dark eyes and eyebrows. Her mom's figure, too, less obvious in how differently they dressed it.

Standing between her parents in the kitchen, Nina felt both like the middle of a Venn diagram and entirely outside it.

They took their tea to the living room, Nina and her mom adding some cold water to theirs, Nina's dad adding some milk. He turned the volume on the TV down, but the commentators' faces kept flickering on it. Did he have a playlist going or was this just an infinite livestream?

"I've been asked to teach the class on the Odessan Jewish literary scene again next semester," Nina's dad shared. "Which is interesting considering we couldn't get enough people to sign up for the class to happen at all the year before the war started."

"We have to do what we can," Olga said vaguely. Tiredly. They were all tired.

"Should we watch a movie or something?" Nina suggested. "The Pokrovsky Gates?"

"We could watch something a little more subversive and intellectually stimulating than that," Peter said, finally pausing the damn commentators and pulling up the YouTube search bar.

"If you can find it on YouTube for free, sure," said Olga.

Tarkovsky's films all cost money to rent.

They watched The Diamond Arm, which had anything possibly subversive censored out of it before it ever premiered, but was also Nina's mom's favorite.

Nina sat between her parents on the couch and very slowly sipped her tea, feeling younger than she'd felt since college.

Nina usually had Sundays and Mondays off, so she woke up late the next morning and at loose ends. Her parents had both left for work already, and the house was big and empty. Her mom left a note on the kitchen counter for her next to a clingwrapped plate of crepes, reminding Nina to do the laundry since she was home today.

Nina ate the crepes with sour cream and drank a cup of tea, then put on the laundry in the basement as requested.

The basement was mostly finished. In addition to the laundry machines and storage, there was some space Nina had used for her "studio" back in high school. A corner next to the small, high window that let in a slice of natural light, supplemented by two tall floor lamps she'd dragged in from upstairs. There was an easel and canvases she'd used for her art school application portfolio. A pile of half-empty paint tubes on the floor, next to some rags.

Nina turned on the washing machine and thought about trying painting again. The basement smelled of dampness, a wet cement scent no amount of paint or carpeting could cover up all the way. She could add the artificial smell of fresh acrylic paint to the mix, if she wanted to. But what could she paint? In high school she did the usual stuff: still lives and self-portraits and whatever her art teacher told her to do. In college she drew for assignments: beer can designs and album art and movie posters and book covers. What could she paint-draw-make without that?

She went upstairs to get her pocket sketchbook and flipped through it as she went back down. There was her unfinished study of Rose O'Neill's drawings. Maybe she could try imitating that in paint? With big, heavy globs of color instead of dense cross hatching. Or maybe...

The laundry machine hummed in the background, making the floor buzz ever-so-softly beneath her slippered feet. Nina put on her go-to work playlist (carefully curated over the course of her college career) and one of her dad's old shirts, and loaded up a brush.

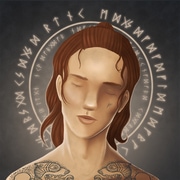

She wasn't usually a fast painter, but she was trying to go for expressive this time, so by the time the first load of laundry beeped its completion she had a recognizable figure on her canvas, in fat impasto strokes of black and white paint. She moved the laundry and let a full song play through on her playlist before taking another look at the painting.

"It needs color," she said out loud, "but is red too cliche?"

Whatever. She tried adding red anyway, just to see what would happen. Brightening it with yellow and darkening it with blue, trying to make the color glow through the light and shadows she'd already put down. A red like... Goldie's signature matte lipstick.

The figure she was painting wasn't Goldie. It was honestly barely even a figure at all, just a pile of bulging shapes that suggested the possibility of something humanlike. She was thinking about Rose O'Neill's creatures again, their grotesque faces, their tantalizing ambiguity. The way they curled around maidens a fraction of their size, making them feel safe and small. The lines so precisely controlled.

Nina dropped the brush and started smearing the paint around with her fingers, practically sculpting it, hoping that by touching the paint directly she could make a viewer feel how badly she wanted to be touched.

By the time her dad came home, Nina was mostly done. The empty canvas she'd had lying around was pretty small, and there was only so much tweaking she could do to a painting so loose. Acrylic was less flexible than oil, and dried quicker into a gummy, plastic crust.

"Oh! There you are," her dad exclaimed as she emerged from the depths. "Thought you went out somewhere."

"Laundry," Nina said. She didn't want to mention the painting. He could get overexcited, and assume this meant she was back on track for the career she still wanted to have. Or he could get critical and try to tell her the anatomy was off somehow. He supported her in several ways.

"How was work?"

Her dad made a face. "Coming up on finals, so office hours were actually busy today. Always surprised by how many people leave studying to the last possible minute. What should we do for dinner today?"

Nina opened the fridge, felt overwhelmed by choices, closed the fridge. "What are you thinking?"

"Could just do pelmeni. Fast and easy." Frozen pelmeni, small meat dumplings, were a college student's staple in the post-soviet states because of how little effort they required to be tasty and filling.

"Sure," said Nina. "Then I'll make a salad."

"And we'll be done before your mother gets home!"

They got to work, maneuvering around each other in the small kitchen with ease. Nina liked helping her dad cook, had liked it since childhood. This was a part of living with other people she enjoyed. If she had to move out and live with roommates again, Nina decided privately, it would have to be with someone she can cook with.

Her dad hummed something under his breath as he reached for the spice packets, something familiar to Nina from previous times she'd caught her dad humming or singing softly to himself. He wasn't exactly musical, but in the Moscow intelligentsia mileu where he'd grown up, the music was always in the background, as part of the communal kitchens as the simmering pots of soup on the stoves. It came with him to the States, and Nina found she'd inherited his fondness for having something playing at all times. She chopped the vegetables for the salad to the sound of that hum, the pot of pelmeni bubbling along.

She went back downstairs after dinner and tea and looked at her painting again, wondering what to do with it. The sun had set while they were eating, and the incandescent floor lamps made the colors look overly warm. She snapped a photo anyway, deciding that filtering it might help correct the colors. It kind of did. She sent the filtered version to Cory and then, after some thought, to Goldie as well. She could probably post it online, but that seemed scary. She considered sending it to some of her college friends, but that seemed scary too. What if they told her to submit it to a gallery? What if they had critique?

Comments (0)

See all