“The Fortress of Serberos was home to the empire’s greatest martyrs. Although a demon might make its way there every once in a while, make no mistake; most of its prisoners are innocent. Think of it as the Imperial Family’s personal graveyard. All it takes is an order, some falsified documents and evidence, and some poor soul will find their heads in the gallows…or their bodies rotting at its cells.”

-Unabridged journals of the Imperial Scribe; c.15 p. 42

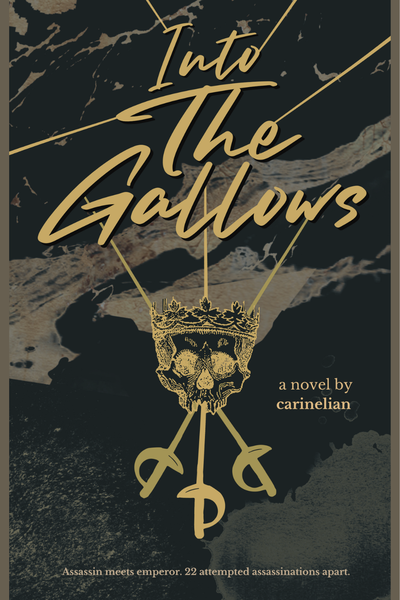

Aster Mortem will die as a spectacle.

Perhaps he had the late emperor to thank for this little parting gift, but he wished that it hadn’t taken so long. He had always imagined going out with a bang – being held back by guards, shot down on horseback, or even falling out of the empire’s highest tower – anything that involved a grand chase and an even grander exit. A spectacular death is only fitting for a man who lived with the shadows; at least in death, he would die in the light.

However, things had changed. Three decades will take its toll on a man, and being the empire’s (once) most renowned assassin makes Aster no exception. Even without a mirror, he could tell that his once firm and taut muscles had long deflated, his strong bones had gone brittle, and his face – his beautiful face – had long suffered the cruelty of time. He would die as a spectacle, yes, but an old one at that, like a rotten fruit past its prime.

He should’ve died in that throne room long ago, as a handsome, sarcastic young man. He may have been put in an awkward position (being strapped down on the floor like some wild beast) and beaten down (like a stray dog), but at least he’d have gotten a moniker like ‘silver arrow’ or ‘night blade’. He would have gone down in history.

You will die, but never before me. You will be sent to the Fortress of Serberos, down the coldest cells, where you can spend your remaining days wondering where you went wrong.

He cursed the emperor. Cursed him for taking so long to die, cursed him trying Aster’s fate with him, cursed for his somewhat miraculous survivability despite Aster giving his damned best in all those 22 attempts. To be fair, he had tried everything: from poison, arson, black magic, you name it. But the emperor just won’t die, the same way he had taken three decades to finally, finally take Aster with him.

But the most unforgivable blunder of it all, the emperor could have died just a year earlier and spared Aster the pain of losing a friend, no matter how unlikely their circumstances were. As it turned out, the rumours of the fortress being home to martyrs were true: he’d met many poor souls down here, most of them innocent.

Thankfully, Aster wasn’t one of them. As a matter of fact, he was so guilty that he wished he had one more name to add to his body count – the Great Emperor Dominique Sibylla – who for some reason appeared to have died all of a sudden. Aster was nothing if not charming – even the guards that he’d bonded with wouldn’t tell him how or when exactly His Highness had died.

“Congratulations,” a guard had said one day, as he passed by Aster’s cell. “Your time’s almost up.”

It should have been ominous, to be told that you’re dying, but to Aster it brought relief. Dying meant freedom. Whether or not there was afterlife, at the very least, Aster wouldn’t spend his remaining days longing for the voice that used to occupy the nearest cell, wouldn’t spend another day staring at the damp, mossy walls, and wouldn’t spend another second wishing he hadn’t taken this job.

Aster couldn’t wait to finally lose his head.

***

“This isn’t necessary.”

Aster shared a table with a nun, with his hands and feet bound in chains. Behind him stood the guards tasked with bringing him to the executioner’s stand – yet for some reason they’d taken him to this sister instead. A cup of tea was laid on the table, and some long, forgotten instinct urged him how he could easily break the cup and use the shards to create a hostage situation.

“It’s not necessary, yes,” the sister agreed, with a voice so soft it melted Aster a little. “But His Highness insisted that you receive all the support you need, especially after suffering such a c-cruel sentencing.”

The sister’s voice wavered at that last part, and her eyes shone as if she truly pitied the man before her.

“May I ask for your name, sister?” He tried, eyeing the guards behind him. He even raised his hand a little bit, as if to say, see? I mean no harm.

The sister glanced upwards, probably waiting for the guards to signal their approval. She took a deep breath.

“I’m sorry,” she started to say, “but I believe it’s better–”

“Just let her do her job, Mortem,” one of the guards urged, effectively cutting off the sister. “She doesn’t need any more deaths in her conscience.”

Aster gave them a pointed look at that. As if she was the assassin out of the two of them! But in the end, he understood what the guards meant: there was no point for a dead man to meet new people. The ending would be the same anyways – he would head to the gallows, and they would head on to their lives.

“My apologies,” he relented. Then, for good measure, Aster shifted upright on his seat and regarded the sister with a small smile. “Let’s just get on with it, then. Say your prayers, sister, bless me or whatever. The quicker the better – I have an appointment.”

As soon as he said those words, the tension in the room seemed to have lessened. Even the number of guards decreased, almost as if they were just waiting for him to wave the white flag before they fucked off. Good riddance.

The sister, on the other hand, could only stare at him, probably unable to imagine how an inmate can remain calm in the face of death. It shouldn’t be a surprise that Aster was built differently, he had three decades to prepare for this moment!

However, what came out of her mouth next was no prayer or blessing. She stood up, leaned close to his ear, and with bated breaths, she said:

“Your friend has asked me to relay this to you. He says, ‘the only way out may be through, but there is another, if you are willing. There are people here who owe me favours. Drink from your cup if you want out’.”

Aster’s blood ran cold.

If the sister said anything more, he didn’t hear it. His ears were ringing; at that moment, all he could do was repeat the words over his head: your friend, your friend, your friend.

Aster Mortem only ever had one friend over the course of thirty-years.

“Excuse me?” He stood up and slammed the table, spilling the tea. “What the fuck did you just say?”

Naturally, the guards were quick to restrain him, but even the sister in front of him seems to know that Aster was in no condition to hit someone, much less a woman. She stood in her seat, spine ramrod straight, and she stared at Aster with the eyes of a completely different person – an opposite of the demure, doe-eyed sister he had met moments ago.

She straightened up their cups and poured another batch of tea with the grace befitting of a noble. Only then had Aster realised that her hands were littered with scars – the kind you only see with a swordsman.

“Drink from your cup if you want out,” she repeats. “We don’t have much time.”

Aster looked at the guards. This-this woman was speaking so openly about breaking him out! Shouldn’t they alert the others and arrest her? Unless…

Something in his chest seemed to have been clawed out. “Don’t–don’t tell me you’re in it, too?” He asks, in a voice too broken to be called his own. The Aster of the old would have beaten the man he had become bloody, just for being so weak and vulnerable. But what can he do?

Normally, one would rejoice at the prospect of being saved by the bell. But to think that all this time, his friend had such resources at his disposal, and he chooses this exact moment save someone like Aster on his day of execution…

When Aster spoke next, his voice came out too raw: “What are you going to tell me next? That you broke him out too? Tell me, is he–”

“He’s dead,” the sister cut him off, seemingly following the line of thought before it fully sprung. “I asked him the same question once, when he sat in that same chair. But he said you need this more. He actually ordered me to break you out, but looking at you just now, I figured you could use a choice.”

Aster glanced at the clock. 11:15 in the morning. He was scheduled to die at 11:45, just a few minutes before lunch. He had enough time to make a break for it and reclaim his life. Maybe, if he felt like it, he could go for the newest emperor’s head and see if this one is just as tenacious as his predecessor.

But Aster was already old, and during his time at the Fortress, the voice from the cell next to him had taught him many things. From the feasibility of assassination attempts across different towers, how they would make a frugal, law-abiding life post-prison, to hypothetical prison breakout scenarios, those years he’d spent in that damp, cold cell were probably the best he’d ever had (minus the freedom), thanks to that voice. He hadn’t even gotten his name or seen his face.

Now, he had one chance.

He glances at his cup, before making himself more comfortable in his seat. He sat as though they were simply meeting from a tavern, and not a dead man’s final stopover before he headed to the gallows.

“He never did tell me why he’s in there,” he told the sister, who only chuckled at his obvious choice.

“His crime is nothing compared to yours,” the sister said. She took off her hood and revealed waves of brown curls framing her face, wild and untamed. “It’s not that hard to imagine why he’d never speak of it.”

“You speak of him fondly,” Aster says carefully. “Are you–”

Quick as ever, the sister caught on. “What-no. No! Have you seen MY age? I was a child when I first met him. But he saved me, though. A life for a life and more. He’s like a big brother to me.”

Aster took another glance at the clock. 11:25.

“I see. He didn’t tell you about me, either,” the sister’s voice turned somber. The words were spoken like she was trying to soften a particularly rough blow, although whether it was for Aster or herself, it was hard to tell.

They spend the remaining minutes in silence, with Aster staring at his cup and the sister staring at him. Aster had decades to prepare for his final moments, but never imagined that it would be so…anticlimactic.

“Are you sure about this?” The sister finally asked, once the clock hit 11:30. “I’m not sure what you really take me for, but skill is no matter when it comes to me, you have my word. I’ll break you out.”

The sister might’ve fooled Aster for a moment, but now that he knew where to look, he could easily tell how her movements held a certain vigilance about them, as if she was ready to spring to action at any moment. Perhaps his years in prison had dulled him.

“I have no doubt about your skill,” he assured the sister. “But I was waiting for this, there’s no way I’m breaking out. That old bastard went through the appointment himself. I’m just meeting him. That’s all there is.”

He patted the sister’s head for a good measure. “You’re a good kid, keeping your promises like that. Thank you.”

When the sister finally looked up at him, it was as if she was seeing him for the first time.

Such a shame that it would also be the last.

***

There were only a few people present at his beheading.

There was a priest, who prayed for his soul, some guards, a judge to read off his crimes, and the executioner. Somehow, against his expectations, the reality was more grim and dull than the one he had in mind – instead of bustling crowds and angry mobs chanting for his death, Aster was met with a dimly lit courtyard and badly assembled members of a low-budget play.

“Aster Cassius Mortem,” the judge read, “as per the order of the late Emperor Dominique Sibylla, you are hereby sentenced to die following his death. Your crimes are as follows: twenty-two counts of attempted murder, forty confirmed hits as a mercenary, unauthorised dealings at the black market, numerous attempts of bribery to officials, and treachery to the empire by colluding with insurgents. Do you have anything to add?”

Aster let out a whistle at that. He had knelt before the judge, the chopping block right beside him. His bare knees pressed against the stone-cold pavement. “Nothing. I’m actually surprised you all managed to get this documented.”

The judge regarded Aster through his nose, seemingly wanting to put up airs, until he realised that there was no audience to act for. He slumped in his seat. “You’re awfully chipper for someone about to die.”

“I kill people for a living,” Aster shrugged. “It’s only natural that I’m prepared to die.”

“Fair point,” the judge hummed, pleased with his answer. “Let me rephrase my question then. Do you have any last words?”

This is it? Aster thought. He stared at the sky — right towards the cerulean canvas that he’d been deprived of for so many years. Strangely enough, it didn’t feel like freedom. There was no catharsis, no pleas for redemption…not even a hint of nervousness or anticipation. His chest was hollow, and even if his eyes strained, it only did so because of sunlight, and not of tears.

He tried to commit this moment to memory. There was a priest and his empty prayers, paying lip-service. On the side, he had bored guards that knew better than to stay vigilant for a dead man. Behind him stood a minimum-wage executioner who was neither imposing nor intimidating – only there, as a reminder of what came next.

Then there was the half-assed judge, who had donned a wig and a cape, read his crimes, and reclined in his chair. His eyes, Aster finally noticed, held an otherworldly hue that was either a trick of the light or a dying man’s hallucination.

“This is boring,” he said to the judge. And then, almost nonchalantly, he added, “I wish I could go back.”

Maybe rotting in his cell was better than this. At least they would have horror stories and legends of the infamous assassin that was locked-up in the cells of Serberos until he died, who carried so much malice and killing intent that he turned into a vicious ghost. Or maybe, if he stayed long enough, a more fucked-up inmate would come in and they would have a cage match. Anything would be better than dying in this lonely, decrepit play of an execution.

“That’s it?” The judge sat forward. The light in his eyes was growing brighter.

Aster shrugged. If he said anything more, then that would technically be his last words. Horrifying.

He had to admit, though: as they laid his head over the chopping block, he felt his heart race a little, waiting for the blade to fall. He’d been told that decapitation was one of the most painless ways to go, but they were wrong – there was a brief moment of intense pain as the blade severed his spine, catching at a particular snaggy bone that he swore the executioner dug on his neck a little harder.

And then, nothing.

People don’t usually open their eyes when they die, but somehow, Aster did.

![[1] A message from the dead](https://us-a.tapas.io/sa/45/5c68b11c-1b6a-48ea-ad0c-2dbf933f5aeb1.jpg)

Comments (1)

See all