“If the general dies, then so does the empire. That was the irrevocable truth, for there was no else who would have earned the people’s love, the respect of the northern wolves, and the fear of the invaders.

However, something else came crawling back as soon as news of the general’s passing hit the capital. The opposite of a saviour. The antithesis to a people’s champion –

— the empire’s scorn.”

-Unabridged journals of the Imperial Scribe; c.189 p. 12

By the time Aster was done painting the snow red, the sun had made bruises out of the sky.

He laid flat over the snow, back against the cold. He had no idea why his body felt pain and exhaustion – dead as he was – but his muscles burned with a familiar sensation, aching with the feeling of having wielded heavy swords and thrown staggering punches. His chest throbbed as if it broke a rib, while his ankle didn’t quite feel like it was in the right place. There was a sting on his sides, and when he pressed a hand against it, it was warm.

Strangely enough, in this cold rendition of hell, Aster felt alive.

“Aster!” His mother’s voice called out. She must have broken out of her panic come sunrise – that, or the obvious lack of fighting. And it hadn’t been just her: slowly but surely, the rest of the surviving villagers were coming out of hiding.

This certainly didn’t happen before, he thought, feeling lightheaded. His sister and his mother gradually came to vision, crying and sobbing his name. Another hand pressed to his side, causing him to almost bite his tongue in pain.

“You’re so stupid!” Dahlia cried. She ripped a piece of fabric from her shirt and began pressing it against Aster’s side. More pain. He cursed and tried to push her away, only for her to swat his hands down. “You could’ve died!”

His mother cradled his head on her lap, fat drops of tears streaming down her face and landing on Aster’s cheeks. “Stupid child. Stupid, stupid child.”

Aster’s gaze went to the sky. At this point in time, the sun had coated the horizon in shades of yellow and gold. That was strange. In the past, the morning after the massacre, the snow had poured relentlessly, covering the dead bodies in a blanket of ice. A final consolation from the winter hell.

“I’m sorry,” he reached out to wipe the blood off his mother’s cheek. Thankfully, this time, it wasn’t hers…or Dahlia’s. Aster’s own hands were coated red, but for now he had been spared of the two murders that he’d actually regretted.

“You should be sorry,” his sister gave him a little flick on the head. “What do you think we’d have done if you died, huh?”

But I AM dead, he almost said.

The pain said otherwise.

****

“Where did you learn to fight like that?” Dahlia asked. She sat beside Aster, dressing his wounds with an efficiency that Aster himself never quite grasped – even with all his skills as a top-notch assassin. His mother could never be entrusted with anything that came with blood, but Dahlia was different. She never shied away from dirty work, and if fate would have it, perhaps she would’ve grown up every bit as a skilled fighter like Aster was…or better.

Now she can, Aster thought. He would make sure of it.

“It came to me…in a dream,” he whispered. The story of the twenty-two counts of attempted murder, forty confirmed hits as a mercenary and other crimes would have to come later. For all he knew, maybe they never really happened, and Aster’s thirty years in prison was nothing but a long, dragged out nightmare.

He didn’t realise that Dahlia had long stopped patching over his cuts, and instead fixating on his face, as if committing it to memory.

“You used to cry at the thought of killing foxes,” she argued.

“...there’s nothing to cry about killing pigs.”

Dahlia let out an offended gasp. “Aster! Since when did that mouth of yours–”

As if to spare him from the coming scolding, the curtains of the hut flew open, letting in a burst of cold hair inside their home. His mother’s face was flushed, and for a moment she appeared to have been too flustered for words, until her gaze landed on Aster.

She opened her mouth to say something, but decided against it. This sent a burst of terror in Aster’s spine, and he forced himself to get up, prepared to put up a fight. Could there have been remaining caravan bandits? Or were there reinforcements?

A figure came up behind his mother, tall and imposing. Instinctively, his hands fumbled at the medical supplies around him. Even a pot of water can kill if you bludgeon the head hard enough.

“Please be at ease,” a deep voice assured. “We are the Imperial Army, we mean no harm.”

His mother stepped to the side, bowing her head a little bit out of respect for their visitor. True enough, the man wore the army’s trademark winter coat, glistening white to blend with the snow. It made them easier to spot too, especially if they were stupid enough to bleed.

The whiter the coat, the more skilled the soldier, someone told him once. It takes a lot to keep their coats clean. Even harder for their blades…or their hands.

This man’s coat was pristine.

“My name is Percival Ettorre, General of the Ambros Imperial Army,” he announced. “We came here after catching wind of the caravan, and we hoped to get here before they burned another village.”

He glanced at Dahlia, the state of their hut, and towards Aster’s multiple wounds. “However, it appears that we were too late.”

I’m sorry, said the same voice in the past. We were too late.

It appeared that the General was destined to not make it time no matter what, Aster concluded. Both then and now, the only constant was the General’s arrival, and their fateful meeting.

Aster scoffed, “There’s no need to be sorry. I wasn’t counting on your help, anyway.”

***

In the past, there had been a boy being beaten within an inch of his life as punishment for killing two perfectly good ‘items’. Nevermind that the items had been a mother and a sister. Nevermind that the boy was their family. His figure was small as he curled up on the ground, taking punch after punch, barely even moving.

Aster held no regard for his safety nor cared to avenge his circumstances at the time. In his mind, it was the easiest to follow his family to the grave, or wherever kin-killers go when they died. The man wearing a bear pelt – the one he just severed a limb from and killed – had been the one to dig his heels onto his face, forcing him to eat the snow through bloodied lips.

“That cost us two pouches of copper!” He gritted out, spit flying everywhere. “You’ll fucking pay for that, boy! You’ll work your ass off ‘till you cough blood, then when you’re done, we’ll sell you for parts so you’re actually worth something—”

There was the sound of something being drawn, and then, an obscene squelch. Blood poured from the man’s mouth, rendering him unable to finish any more of his threats. He slumped next to Aster, his dead weight of a body reeking of alcohol and filth. Aster didn’t dare close his eyes. Above him, a reaper had seemingly materialised out of nowhere, cutting down the bandits one by one.

Aster watched as the light slowly faded from the bandit’s eyes. He coughed up for air once, twice, then breathed his last.

Too swift, Aster remembered thinking. He had perished too fast.

His mysterious saviour had been a man dressed in a white coat, with droplets of red adorning the leather like rubies. He had a bloodied sword and even bloodier hands, but what amazed Aster was the fact that it didn’t appear to belong to the man. His eyes had been as gray as the winter sky, while his hair had been how Aster imagined the colour of wheat.

He whispered his apologies. Without knowing what transpired within the village overnight, he knew he had been too late. Back then, General Ettore of the Ambros Army did not offer Aster a hand, nor his condolences.

“Here,” he threw a dagger on the snow. “You survived for a reason, even if the reason is to kill.”

Live, went the unspoken words. The General spared no thought whether or not the boy had plans to turn that blade on him, himself, or even the future emperor. Perhaps, in that moment, he saw that no compassion or recompense would suffice. A clean life would’ve been impossible too, given that the General killed for a living as well.

Swallowing his grief, Aster had picked up the blade and swore that the world would regret that someone like him didn’t die on that fateful night. He and the Genera had parted ways, convinced that this tragic encounter would be their last.

***

In the present, a boy lay on a pile of furs, having killed a whole caravan of bandits by himself.

“How did you do it?” The General asked, once they were left alone. He stood in front of Aster, refusing to sit or kneel, and Aster, retaining the pompousness of a death-sentenced criminal, refused to sit up or stand. Which leads to this absurd portrait of a peasant looking down at a general, and a general whose words suggest that he was looking up at the boy in front of him.

Aster considered a sarcastic remark. But his mother and sister were outside, and if he guessed correctly, then the rest of the soldiers must be too. He’s had his own fair experience of Imperial soldiers slaughtering civilians when they believed that there would be no consequences. In a place like Taratus, only the strong dictated what consequences were.

“They were bandits, not trained killers,” he said simply. In the end, the stark difference in their experience shone through: the bandits were barely able to swing their blades properly, while Aster had been trained to kill anything and anyone that moves.

“Let’s help each other here, Aster,” the General threw out his name, just like that, as though it were bait. “Bandits or no, twenty people don’t just die, much less by the hands of one person.”

“They just did,” Aster shot back. And then, for a layer of safety, he added, “...sir.”

The General’s face remained impassive. If he considered signing their death warrants right then and there, it didn’t show. At this point, Aster failed to understand why the logistics of what he just did would matter – after all, the empire has long abandoned the outskirts, and everyone knew that the army is only here to shore up defences or scout for gold. What difference does it make, if one puny village boy can hold his own against some bandits?

He’d expected the General to leave him alone, or quite possibly act out, but the man only ended up running a hand through his hair.

“Very well,” he sighed. “I’ll give you time to rest, and I’ll explain why we need your cooperation much later. Like I said, we mean no harm. We came here for help.”

He pulled back the curtains and stepped outside, leaving Aster completely alone.

Truth be told, Aster believed him. For all the Imperial Army’s sullied reputation, General Ettore was the light to their shadow, a true people’s champion whose deeds went down in Ambrosian history. He meant every word he said and only ever raised his sword to protect the people.

If only he didn’t die behind enemy lines, sacrificing himself in that decisive battle at the borders, perhaps he would have even changed the empire’s fate. Had General Ettore made it back to Ambrosian soil, the empire would’ve handed even the throne as a reward for his heroic deeds, and carved a future in which there would be no Emperor Sybilla. No tyranny. No resistance. No thirty years in prison, no failed attempts at regicide, and no future in which an innocent man would end up adjacent to Aster’s cell.

In his mind, he saw the judge on his execution day, assessing him with that strange, otherworldly eyes and even stranger expression. Aster thought he imagined it, but now that looked back, he thought he saw the man smile upon hearing Aster’s final words.

I wish I could go back.

Before he knew it, Aster had gotten up from where he laid, despite his shaky legs and whole body screaming in pain. His soul may have come from another time, but had forgotten that this body had yet to grow stronger bones and tougher muscles. It had yet to earn all the scars that made Aster a household name in the darker side of the empire, had yet to bleed his way to infamy.

He stumbled his way out of the hut. He needed to find General Ettore. Now that he had saved his mother and sister from their deaths, perhaps he could save the empire’s white knight, too.

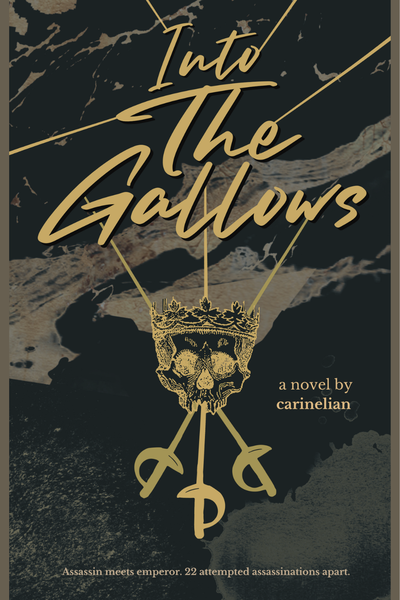

![[3] The Empire's White Knight](https://us-a.tapas.io/sa/45/5c68b11c-1b6a-48ea-ad0c-2dbf933f5aeb3.jpg)

Comments (0)

See all