Leandros Nochdvor had a secret: he loved ghost stories. Not just any ghost stories, but the trashy, serialized variety that sold on street corners for a penny. Losing himself in a cheap romance and dubious haunting beat confronting his own ghosts, the failures and losses that clung to him like cobwebs.

As far as guilty pleasures went, this one was relatively harmless, but he’d be the first to admit it had caused his current predicament. He’d just wanted a new chapter to read. He hadn’t counted on meeting a ghost of his own.

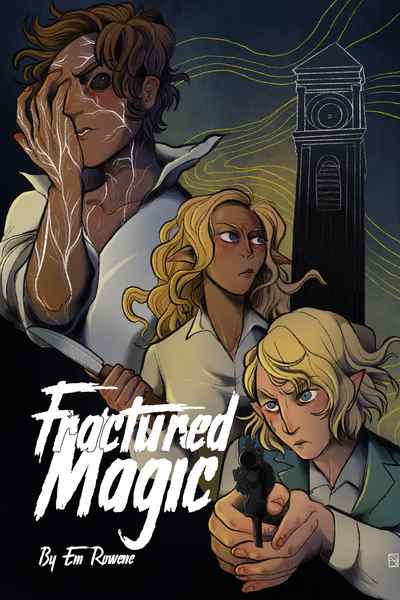

He’d been browsing market stalls with his cousin when he’d spotted the latest installment of his favorite story, sitting in a newsstand across the street, taunting him. He’d recognized the cover halfway down the block: the black and white illustration depicted a loosely dressed woman wrapped in her lover’s arms, a dark-windowed house looming behind them. It was scandalous, as scandalous as the story itself tended to be, and Leandros couldn’t possibly buy it in front of the Crown Princess of Alfheimr.

Back home, he had a system. His favorite penny dreadfuls had limited print runs that sold fast, and while normal people could borrow copies off friends and neighbors when they missed a week, Leandros was a Prince of Alfheimr, the Hero of Histrios. No one could know about this guilty pleasure of his. So once a week, he donned a disguise and stole out of the palace, holing up in a dark cafe to catch up on the latest chapters of his favorite stories. It worked well back home, but now he was traveling with family. When they weren’t on the road, they were guests in someone else’s home. It left little opportunities for sneaking out.

So, when Leandros saw that corner newsstand, he’d looked over his shoulder to see if Rhea was watching. And she wasn’t. All he saw was her parasol, her back to him as she perused a local jeweler’s stall. It was the best chance he’d get. Penny already in hand, he stepped off the sidewalk into the street, but before he could make it any further, a small body crashed into him with all the force of a freight train.

He and his assailant both went stumbling: the assailant to the ground and Leandros into a florist. The florist, in turn, reeled and knocked a tub of wilted roses off her counter, dumping sickly sweet, freezing water all down Leandros’ pants. He swore and tried to shake the water off, all his annoyance and anger ready on his tongue by the time he turned to his assailant.

Finding her on the ground, the words died and instead, he offered her a hand. She hesitated before taking it, her face obscured by a heavy cloak and draping hood, but then she let Leandros pull her up, her pale hand clammy in his own. And as she straightened up, Leandros glimpsed beneath her hood.

A chill ran down his spine.

To him, ghosts were only ever a metaphor. He didn’t believe they were real — he never had. But looking at this woman now, it was the only word that fit. A mask covered the lower half of her face, but Leandros could tell she was orinian, from across the valley. What skin he could see was bloated and mottled, torn open by wounds that cut across her pale forehead. Only her eyes had any life to them, feverish and bright beneath her hood.

She met his eyes, and Leandros swore he heard her laugh. Without warning, she took off running. What could he do but give chase?

“Leandros!” Rhea called after him.

It was instinct that forced Leandros on. The crowd resisted him, pushed back against him, but he pushed harder. He elbowed his way through, to surprised exclamations and much grumbling, then finally shot free of the crowd like a bullet from the barrel of a pistol. Always, he kept the back of the woman’s raggedy cloak in his sights. He didn’t know why, but he felt that losing her now would be a mistake. Maybe he’d been reading too much fiction, but he couldn’t shake a sense of dread.

Up ahead, he watched the edges of the woman’s cloak disappear around a corner. He turned the corner himself only seconds later, but when he did, she was gone. Leandros skidded to a stop and looked up and down the street. It was empty. There were no side streets, no alleys. Nowhere to go.

“Shit,” Leandros said to the empty road, pushing his golden hair out of his face. He rested his hands on his —wet, cold — knees and paused to catch his breath. “Shit.”

He’d followed the woman almost halfway across Illyon. This was a neighborhood he knew well, one he’d visited often, in another life. It was quiet, mixed residential, not wealthy but not poor, either. The cobbled road was pock-marked and the dresses in the storefronts at least several seasons behind Alfheim, the capital city. Leandros ached with a nostalgia he had neither the time nor energy for, in that moment.

He hated Illyon. It was a dingy, self-important little city, industrial and “progressive” in a way that meant progress only for the rich and lucky. Factory smoke filled its skies and buried the suns, and beneath the smog was a smell so foul it hurt to breathe, the product of a sewage system that failed to fit the growing population. It had only gotten worse in the sixty years since Leandros' last visit, and he was less than impressed. If Illyon was good for anything, it wass thi: ill omens, strange happenings. Ghostly women that appeared and disappeared in a miasma of bad timing and rotten luck. There would be no finding her, now.

He needed to get back to Rhea, shouldn't have left her in the first place. They had meetings and responsibilities to attend to. How could he run off chasing ghosts? Illyon was full of those; he should've known better. As he passed back through familiar streets, he passed a group of children playing skip rope, chanting an old rhyme to the beat of their jumps:

Taurel, taurel, old stone and coral

Where do you end your reign?

Spread through the valley, down to the trees.

You will be Egil's bane.

While Leandros slowed without thinking, watched them without seeing, the girl holding one end of the ropes slowed, almost tripping her friend in the middle. “Ansel, what's taurel?” she asked.

The boy holding the other end, slightly older than his two companions, shrugged.

Leandros didn't mean to answer, but he did, the kids all turning to look at him. “It's a flower. It grows north of here, on Unity's island." He cleared his throat, then added, awkwardly, “The rhyme's about Unity.”

“But wasn't it an alfar that killed Egil?” Ansel asked, regarding Leandros with suspicion. “He went crazy and killed a bunch of people, and even Unity couldn't stop him!”

“My teacher said Egil was a great hero,” said the girl in the middle, glaring at Ansel. “Heroes don't kill people.”

“They do if they go crazy,” Ansel countered. Like Leandros, he was alfar, with pointed ears and catlike pupils.

“There are conflicting accounts,” Leandros said, feeling a little ill. He didn't know how he'd expected to survive an outing in Illyon without hearing the name Egil.

“Egil used to live here, you know. He had a house, just there. It's a museum now,” the girl with the ropes told Leandros, as if Leandros didn't already know. As if you could spend ten minutes in this Atiuh-forsaken city without learning it. As if, back when the museum was still a house, Leandros hadn't had a guest bedroom made up specially for him, anytime he wanted it. “I went with my class last week, but it was boring. Just a house. I bought an Egil figure with my allowance, though. Want to see?”

“No,” Leandros said, too quickly. “I’m in a hurry, I’m afraid.”

Illyon's obsession with Egil was the worst thing about this city. They worshiped the ghost of a hero they had no claim to while Leandros, who had more cause than any to mourn, faced reminders of his lost friend everywhere: in museums and statues, on tacky restaurant menus and even in children's rhymes. It left a bitter taste in his mouth. He couldn't help but think that if Egil had been here, that woman wouldn't have gotten away. Egil would have known what was wrong with her. Egil would have known how to help.

“Leandros!” a voice called, making Leandros curse under his breath. Slowly, he turned to face his cousin.

Rheamaren Nochdvor wasn’t like Leandros; she was the perfect alfar, always utterly in control. She never ran, she only walked. She didn't get waylaid by inquisitive children or mysterious strangers. She never even cursed, especially in front of kids, but Leandros could see in the irritated draw of her mouth how badly she wanted to in that moment.

Rhea's high fashion stood out in Illyon. They were supposed to be covert, sneaking around without an escort, but she couldn't be anything but royalty. She was tall and elegant, in a rich red dress with a full skirt and puff sleeves, matching her parasol. As a symbol of her status, she wore her long, golden hair down, the pointed tips of her ears sticking out from beneath it. She stopped in front of Leandros, then glanced at the children behind him, her anger quickly replaced by puzzlement. “Am I...interrupting?”

The children, watching Rhea with wide eyes, kept quiet.

“We were discussing Egil,” Leandros said with a wry smile. He gave the kids a playful bow, and the two girls grinned and curtsied back. “I'm sorry to have kept you from your game. Please, excuse me.”

Rhea glanced over the children, bored, then turned to leave. Leandros hurried to catch up, and when he fell into step, she asked, “Egil, really? I don't know why you do this to yourself.”

“It wasn't intentional.”

“IHm. And what’s going on here?” Rhea asked, gesturing all around them. “What were you thinking, taking off like that?”

Leandros scratched his chin, now embarrassed to say. “It doesn't matter anymore. I thought I saw something strange.”

“Strange? You ran all this way for strange? What kind of strange?”

“It's hard to describe. That woman was orinian, but she—”

“Orean is a day's ride away, Leandros,” Rhea said. Her voice was flat and measured, flawless as cold stone. “Of course there will be orinians here.”

“Obviously,” Leandros snapped. Normally, he tried to be patient with Rhea, but it was hard with these ghosts all around him, when every breeze froze his still-wet clothes. Well, at least he was wearing all black. If he’d been wearing one of those white linen suits that were trending in the north, there would’ve been no preserving his dignity or his decency. Perhaps there were benefits to staying in mourning blacks, after all. “Something was wrong with her, Rhea.”

“Not with her legs, given how fast she ran from you,” Rhea said. She examined her cousin's expression more closely. His unease must have been obvious, given how quickly her tone changed. “Well, where did she go? Should we keep looking for her?”

“When are we due back?”

“In ten minutes.”

Leandros winced and checked his watch. She was right. “There’s no time,” he said. “Besides, I have a feeling we won’t find her even if we look. We’re not far from Hampstead Hall; we can be back in twenty minutes if you don’t dawdle,” he said, starting off down the street without waiting for Rhea to catch up.

“If I don’t dawdle?” she hissed. “You — Ugh, Leandros, why don’t we just hail a cab?”

“Because this isn’t Alfheim. We’re not going to find any in a neighborhood like this; we’ll have to get back to High Street before we even have a chance.”

It wasn’t even a bad neighborhood, in the way people liked to call neighborhoods “bad” — not unsafe or rowdy or even particularly lively, but Leandros never would've brought Rhea here under other circumstances. The problem wasn't Rhea — she needed to expand her horizons, see more of the world. It was her father. If he found out, he'd be disappointed in Leandros, and Leandros could never disappoint his King. Not intentionally. But as long as they were already here…

“Look around. Commit this to memory,” he said, even while he himself looked under passersbys' hoods and down alleys for his missing ghost. “This is how most of your subjects live. It’s important to leave home every now and then, see the world.”

Rhea wrinkled her nose at getting orders from her cousin, older though he was. “Rich, coming from you. How long has it been since you’ve left the Palace grounds?”

Of course, she didn’t know about his sneaking out for cheap fiction. That was just as well. “I’m not going to be queen."

In the end, Rhea did as he asked, taking in the city with curious eyes until they managed to hail a cab on High Street. It rattled easily through the market, the crowd parting for it in a way it didn’t for fellow pedestrians. Leandros kept checking his watch on the way, watching the smooth ride shave minutes off their arrival time. The watch's front was dented, the metal tarnished, but it ticked steadily in Leandros' hand. His eyes carefully avoided the initials engraved on the inside.

“Only five minutes late,” he said smugly.

“You're the one who made us late, so why do you sound so proud?” Rhea asked. “There are flowers in your hair, by the way.”

Leandros frowned and ran his hands through his hair. It was the same golden color as Rhea’s and was cut fashionably at chin length, though a single, stubborn lock tended to fall rather unfashionably into his eyes. Sure enough, he shook out a handful of dried petals from his run-in with the florist.

“I had to pay for those roses you ruined,” Rhea said. “I expect you to pay me back.”

Leandros scoffed. “Those roses were already as good as dead. Whatever you paid, it was too much.”

“And what was I supposed to do? You didn't exactly give me time to barter!”

“I don't believe that you even know how to barter,” Leandros countered. “But fine. I'll pay you back if your father doesn't kill me for making you late, first.”

“He won’t. You know how he always defends you. Besides, he’s too glad you finally left the Palace to be angry.” Rhea watched, unimpressed, as he continued to shake out his hair, then took pity and plucked a petal out for him. “We should do this again, when we have more time. I want to see more of Illyon before we return to Alfheim.”

“Maybe,” Leandros agreed, looking out the window. “I do think I'd like to see the house.”

A small furrow appeared between Rhea's brows. All alfar expressions were subtle, Rhea's more than most, but Leandros knew where to look. “Are you serious? Whenever you so much as hear Egil's name, you mope about the Palace for weeks. Now you want to go to his house?”

Leandros’ expressions were not subtle. Compared to his family, he wore his heart on his sleeve. He looked out the window so Rhea couldn't see his face. “It's been sixty years,” he said. To a human, Egil was history. To Leandros, the cut still ran deep. “I know the time for mourning has passed, but I'd like closure.”

Rhea's gaze on him was too heavy, so Leandros added, “I just wish they hadn't turned it into a damn museum.”

“So buy the building. We're here, by the way. Would you like to complain more, or shall we go?”

“By all means, let’s go. I can complain on the way.”

Comments (4)

See all