Gabriel haunted him. The church haunted him. New terror grew within him like the buzz of a harmonica rising, louder, louder, more air, more breath. And at once. As though he had fallen asleep one night, that same delirious and regrettable night, and woke with something in him, a new sort of discomfort in his body that he hadn’t possessed before. The morning after, he rose from his pitiful sleep. He would fall into it peacefully, a fream followed, but then, it would turn,. The slightest thing spoiled it, rotted what warmth he had and turned it into the worst of the worst.

Each night it started, somehow, with a dance. The start of the Eighth grade dance. Across the room, he’d seen across the gym. The flush of purple, green, blue, even red. The girls’ dresses either poofed out in lace and feather ore, or had twisting, turning bits of fabric formed to their bodies. The boys were either dressed to the pristine with their blazers and polished shoes, or lingering around with wrinkled collared shirts they borrowed from their own father.

Across the gym was Gabriel, dressed similar but in a subtle blue. The dream followed as Adam remembered that day. But this was a dream and Adam wouldn’t recognize the memory of the dance in these moments, deep in his own head, with the ringing for a sermon deep through the dream. Our dreams are the bits where we see God. He lives in our memories, an architect of our love.

In one moment Gabriel was across the room, in the next, he was in front of Adam. Small smiled, bright hidden eyed. Then Adam would take his hand and they’d dance across the floor like in the movies they;’d watch. The ones where Lords and Princes reached the hands of their consort and led them across the atrium floor, the music coming to a crescendo, up and up and up until it all fell, fluttering to its end.

But the music never came down. It went higher and higher, jagged like a cliffedge, it rose and Gabriel’s face would slip from him, only his face, darkness shrouded his head, held it, and left him as only a body. And out of the darkness his voice came, “Adam.” And out of the darkness came more hands, skinless, bloodied, bony. “Adam!”

And the hands would grab him, grope him until his skin broke, bled and he was screaming upright in his bed.

And this would be the dream he had every night for a year. Then he’d stop dreaming entirely. And perhaps that was what was necessary for what he would do. Adam might not have understood the ending to the dreaming; all he cared for was the disruption of that same nightmare. Though, it had inspired something in him—a fear, newly stoked, by the reality that he was nothing more than a boy. A boy who now understood shame. After that night, when pain haunted his backside, he imagined it over and over again. He might have mentioned Gabriel in short, quick, uninspiring moments: between setting the table and dinner; parking the car in the driveway after church; getting out of the car for school. Each time, Dad’s eyes were fiery with a promise if he kept going, he would see the same temper once more. And it was as if he sunken. At once, the dreaming stopped unbeknownst to him. He soon gave up on finding Gabriel.What a horror he wish he cou;dn’t admit to, but it was true. There was a disgusting real connection between his ending his own search and the ending to his dreaming. All his dreams.

To this day, everyone filling his home with their black garb, the darkness beneath their eyes, the foreign grief that they had lost someone they knew of.

Adam slumped in a chair off in the corner of the living room as old family and friends made small talk, chittering and chattering like small wild animals out in the woods. A chorus of conversation filled Adam’s senses. He wanted to press deeper into the cushions, disappear, but he couldn’t bring himself to move. It wasn’t his fault, though. You couldn’t blame him for the paralysis that swept over him.

What he saw in the church, in the corner, through the darkness—he hadn’t been sure what it was at that moment, but now, as the small body of a boy, ragged and wretched like a discarded stray onto the street, it became clear to him.

He rubbed his eyes, and drank down two glasses of his late father’s imp[orted Japanese whiskey. Heat ros ein his face but it lacked the temperature to burn any distraction into Adam’s senses. Other than the apparition ahead of him. No one else saw the boy. No one knew he was there. What, when his aunt had walked over, nearly bumping into the ghost. Nearly. She didn’t notice it. Not with her large hips and bright smile and big observant eyes, she passed no glance to it. Him? It (Him).

“Hey,” Lily knelt next to the chair. She poured more of Dad’s expensive whiskey in his glance. She gave him a once-over. “Are you okay?” She scrunched her face.

He scoffed, “Our Dad just died, Lily, but I’m like soooo perf and dandy, y’know?”

She rolled her eyes, then looked to where his gaze planted. “You’re staring off. People are whispering.”

“Let them,” he sipped. As the brown, warm liquid slipped down his throat, eyes never leaving the boy, he felt an urge to say something, ask it.

He pointed, “do you see him– it?”

Lily followed his finger, “see who?” It answered his question.

But there was this..pulling in his chest, or stretching. SOmething was moving, growing, taking root inside him. The truth.

He let his mouth open. It had been years; years and the only person who truly knew what happened that night was Dad. And the pastor. And himself. And Gabriel. COuld he tell Lily? Uncertainty was too vast, too consuming. He swallowed the dryness. He looked at Lily.

“What?” She said, her eyes dimmed. She knew what was happening. She saw Adam’s face shift, the smallest of remodeling. His features molded in confession, exasperated by his hesitation.

Then, “do you remember Gabriel?”

Lily blinked. “I…, Yes? Sort of.”

He nodded, “Can we go outside?”

And they were outside. Outside, they followed the sidewalk. They had no end goal. Adam had no destination. None that he wanted to tell her about. A few minutes went by before, Lily said, “What did–”

And Adam said, “Dad took–”

Each of them stopped. “Go.” Said Lily.

He let out a breath. “Dad took me fishing one morning. Do you remember that? The first time he wanted to and you didn’t want to come?” Lily nodded. And he kept talking and talking ansd explaining and then he was crying and they were hugging. Her face had shifted several times. Confusion. Shock. Disgust. ANger, maybe. And then a sorrow filled her.

With very little time between the information and her processing it all entirely, Lily could only begin, “You don’t–”

“I don’t know anything.”

“But Adam–”

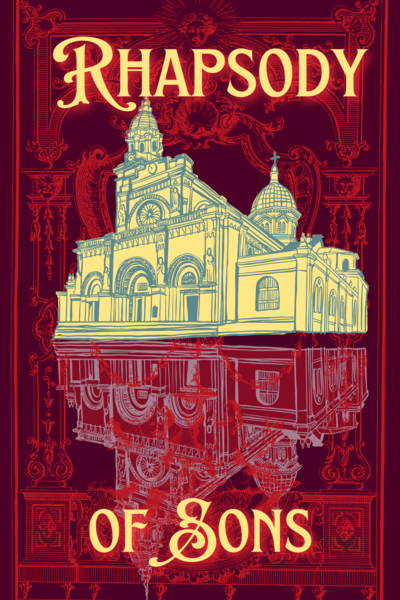

“I don’t want to think that.” A silence fell over them again and Adam stopped walking. Lily looked up to see the church, casting its midday shadow on them.

“I told him I was going to find him. Then I gave up and then—I saw him. Or heard him. He called out to me, Lills.” His voice was frail, small. “I failed him, but he’s– I don’t know where he is but it’s in here.”

Lily grabbed his arm. “Adam, the church is closed.”

“No, it’s not. It’s never closed. It’s a church. Father Carter has a philosophy: to know God is to reach him always.” He climbed the stairs to the grand oak doors and reached for the handle. He pushed. The door opened.

Lily ran up to him. “Adam, you’re feeling a lot, but you’re not going…” He slipped from her grasp. Or she might have let him.

Adam stepped through the vestibule and into the grand atrium of the church. He breathed in the dusty, dense smell of the stone and the polish of the wood. He drew his attention to the darkness at his right. Even in the highest daylight, shadow shrouded it.

Dread filled his veins as motivation inspired him. He took one step, then another. Each one weighed him down as he drew closer. Then he was in front of the hallway right before the door. It was hard to see but he saw the outline of its frame, the hints of its design black and iron.

“Adam, what–” Lily was behind him now, but he [aid her no attention. He took two steps towards the door and reached its handle.

Tears streamed down his face, undisturbed, unbothered, relenting. “I failed him, Lills.”

“I failed him then. I forgot about him. I left him. But not now. Not this time.”

The iron handle was gritty, rough, and freezing.

“Adam, what are you doing?” Lily whispered.

“I’m going to find him.”

“Adam don’t be fucking stupid.”

Adam pulled the handle. The door opened to more darkness.

In truth, what was he doing? What was he going to find beyond this point? But what was behind here? Where did it go? Where did he take gabriel? He had a million questions, and a million more doubts for each one. Adam’s head was swimming and he wasn't thinking right. He was delirious. He was confronted with grief and the space to grieve. He didn’t get that before, but he didn’t need it. Call him a fanatic, crazy, but with each froth of paranoia and anxiety, there was a match lighting his way, a torch, a fire.

“Adam,” Lily spun him around. His face wet with tears, eyes puffy, mind foggy. Yet, she saw it deep in him. This determination, this desire. Something so strong and bold and unignorable that he had to.

She let him go, but he did not turn.

He only choked out, “come with me.”

And, without hesitation, Lily Finch nodded. Adam smiled.

He took his sister's hand and they crossed the threshold of the doorway, stepping into that daring, unpredictable darkness.

Comments (0)

See all