The Chancellor bowed his head slightly — acknowledgment, not celebration.

“The expedition is approved,” he said. “Let us proceed.”

And with that, the future shifted again — no longer held in stasis, but moving.Ax of Lioren lay on his back in the cot in his quarters on the Illenari Space Station. One arm folded beneath his head, the other resting flat across his chest — fingers twitching in slow, unconscious rhythms. The cot wasn’t uncomfortable, but it wasn’t meant for rest either. It was the kind of fixture installed for function, not retreat: recessed into the wall like a concession, framed by a thin band of light that dimmed with breath-regulated settings he had already disabled. He didn’t want the room to respond to him. Not tonight.

The alcove cradled him in a smooth, ovular shell of synthetic fiber — pale grey, matte-finished, pressed so flush into the right-hand wall that it might vanish if not occupied. The curvature was too exact to feel natural, its dimensions clearly calculated to minimize waste, not to ease the body. It held him with that clinical kind of precision Illenari designers favored: supportive, but never soft. Ax could feel the faint seam where the insulation panel met the interior molding, just beneath his shoulder blade. The thermal mesh beneath him kept a constant neutral temperature, neither warm nor cold — as if the room refused to take a side in his rest.

Across from the cot, built into the left-hand wall, was a narrow desk — a simple alloy slab folded outward from the bulkhead, locked into place with silent magnetic hinges. It bore no ornamentation, no integrated screen, no memory coil. A single stylus sat nestled in the recessed groove near its corner, aligned so precisely it may as well have been part of the structure. The desk’s surface was unmarked — no scratches, no smudges, not even the faint discoloration that came with use. It was a surface that had never been touched with intention. It had the sterile calm of furniture that had only ever been issued, not chosen.

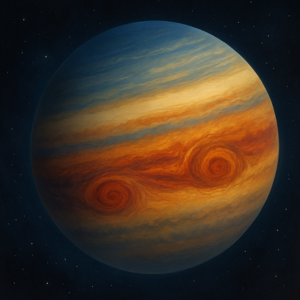

Between the cot and the desk, on the forward-facing wall, a wide viewing panel cut cleanly into the curve of the station’s hull. It was sealed in a tri-layer of reinforced crystal glass and alloy trim, pressure-rated to withstand the tension of orbital drift. The glass itself bore the soft blue shimmer of an active filtration field, diffusing the sharpness of cosmic light into something softer — not less real, only less severe. Through it, Illenar hung in the dark like a monument, its surface veiled in atmosphere, lit by the silver arcs of siphon platforms that wrapped the upper hemisphere in a slow, unblinking ring. Behind it, vast and endless, Typharion churned — its storm bands stretched in bands of violet and gold, the gas giant’s mass so immense it seemed to anchor the void itself.

It was a scene he had seen many times before — from observatories, from high-altitude ferries, from orbital docks and diplomatic windows. And yet it always caught him off guard. Not for its beauty — though it was beautiful — but for its scale. The moons turned because Typharion did. The Commonwealth existed because the balance held. And here, suspended between the two, the station pressed its quiet presence into a corridor of gravity that felt just barely possible.The hum of the station was ever-present — soft, resonant, barely above the threshold of hearing. A blend of circulation systems, thermal regulators, subsonic diagnostics pinging through the hull at intervals too subtle to measure. It was a kind of silence that wasn’t empty, just distant — the sound of systems doing exactly what they were built to do, with no need for interruption.

Ax remained still, breathing shallowly, eyes half-lidded but not closed.

He had not expected the month to unravel like this.

It had begun with a summons he hadn’t earned — not truly. His mother, high councillor of Lioren’s Continuance Council, had appointed him as temporary delegate to the Circumlunar Senate after one of the sitting envoys fell ill during a tidequake survey rotation. The appointment had been swift, procedural, and — as the records would reflect — legitimate. But legitimacy did not erase perception. It did not silence the looks. The quiet recalibrations of posture from veteran delegates who knew precisely what he was, and more importantly, whose.

He had felt it the moment he stepped into the rotunda — not hostility, but something colder: tolerance. The weight of legacy resting uninvited across his shoulders. A seat offered not because of merit, but lineage. No one said it aloud. No one needed to. The decorum of Illenar’s diplomatic class was too refined for open disdain.

They didn’t question his presence. They questioned whether it should be his.

He had told himself it didn’t matter. That the role was temporary. A month. Two, at most. Just long enough to honor obligation and fill the silence with competence. And still, he could not shake the quiet conviction that someone else — anyone else — might have been better suited. More palatable. Less emblematic of a system that whispered fairness but moved through bloodlines like breath.

It wasn’t that he lacked training. On Rheunon, every child of the Continuance was raised with the full weight of their inheritance: instruction in classical rhetoric, public ethics, and procedural theory before they could even parse a legislative clause. He had absorbed it all — dialectic forms, precedent structures, the ancient principles of mutual restraint. But those had never been his passions.What fascinated him were the fractures.

The buried.

The things beneath the words.

Ax had always cared more for what was lost than what was preserved. He had spent countless hours in the sub-academic wings of the Archive Spires, poring over fragmentary texts, disassembled flight records, translated glyphs of moons long collapsed into cultural dissonance. While his cohort rehearsed lines of argument and polished civic enunciations, he traced forgotten myths through procedural footnotes and compared excavation maps against celestial migration patterns. He wasn’t shirking duty — not exactly. But he was wandering, and he knew it.

His instructors called it indulgent.

His mother called it inevitable.

He would inherit her post, of course. That was never in doubt. And he had made his peace with it — not out of ambition, but resignation. The path was clear. The vote would be unanimous. His name had already been etched, symbolically, into the margin of her chair.

So he made history his refuge. Archaeology his ritual.

Research became the thing he did not for position, but for stillness. For himself.

And now, that quiet obsession — that side pursuit threaded in the margins of protocol — had become something else entirely.

In the end, it was fortunate — and for once, uncontroversial — that he had been chosen.

Since the reappearance of the ninth moon, the Senate had moved with uncharacteristic clarity. An exploratory delegation was inevitable, but the question of who would comprise it had sparked familiar calculations: jurisdiction, discipline, symbolic weight. Each moon advanced candidates that mirrored its values — specialists, technicians, minds honed to a single point. There was no shortage of experts, only of perspective.

But Rheunon was different.

His moon did not often produce generalists. The Continuance Council favored precision — students refined through a single discipline, groomed for either law, philosophy, or recordkeeping, or any kind of physical labor, rarely more than one. Depth was valued. Breadth was politely tolerated. And while his cohort had followed that model — taking comfort in structure, in scholarship that obeyed boundaries — Ax had not.He had studied the frameworks, yes. Mastered rhetoric. Passed all the civic examinations expected of a delegate’s heir. But he had also wandered beyond them — tracing the roots of law through cultural collapse, cataloging forgotten ritual forms, collecting inconsistencies in the intermoon canon that no one else seemed curious enough to question.

It had made him an outlier. Even among his peers.

Most of them had viewed his diversions as a kind of indulgent eccentricity — the luxury of someone who didn’t need to prove himself. A soft academicism, charming but aimless. And perhaps, until now, it had been.

But now, those very detours — political grounding, historical fluency, intermoon cultural literacy — had placed him in the precise center of need. The ninth moon was not just a scientific anomaly. It was an echo. A fragment of the system’s forgotten language.

And Ax could speak it.

There had been no internal objections when his name was submitted to the delegation slate. No one suggested another Rheunarian in his place. Not this time.

And for the first time in memory, he did not question it either.

He was not here by inheritance.

He was here because this was what he had been preparing for all along.

A soft chime broke the stillness — three ascending tones, crisp and unobtrusive, followed by the measured cadence of the station’s internal voice.“The final meal of the cycle is now prepared,” it announced, its accent neutral, genderless, layered with just enough synthetic warmth to suggest hospitality without familiarity.

The sound echoed faintly against the curved walls, then dissolved into silence once more.

Ax lifted himself out of the cot with the slow, practiced grace of someone used to moving through small spaces. The ambient lights adjusted as he stepped into the open, trailing the motion of his body in soft, nonintrusive pulses. Near the entrance to his quarters, just beside the panel-locked storage hatch, a tall mirror had been embedded into the alloy wall — narrow, frameless, designed more for verification than vanity.

He stood before it for a moment, studying his own reflection without urgency.

There was nothing extraordinary about him.

He was tall, a little taller than most from Rheunon — a distinction that rarely mattered in the underground dwellings and tunnel systems of his homeworld, where space was calculated vertically and height could be more inconvenience than advantage. His frame was lean, but not soft, built less from training and more from long hours seated in archives, navigating narrow stairwells, ducking low arches worn smooth by generations.

His skin was pale, the kind of pallor common among Rheunarian, but his carried a faint blueish undertone — almost like frost, or the hue of light beneath glacial stone. It caught the station’s ambient glow unevenly, giving him a slightly translucent cast in certain angles.

His hair, dark copper in color, had been pulled into a loose, uneven bun at the crown of his head, strands curling free at the nape of his neck. A woven string secured it — old, fraying in places, dyed in faded gold and ink-dark thread. If one looked closely, the characters of his name had been stitched into the cord in the style of archaic Liorenian script — a gesture of lineage. It had belonged to his fourth-great-grandfather, whose name he bore, passed down not as inheritance but as reminder.

His eyes — wide, slightly rounded, set deep beneath a steady brow — were blue. Or at least, they always had been.

He leaned closer.

The iris, under the station’s cold-spectrum lighting, seemed rimmed with something else. A pale green tint, faint but distinct, curling just inside the outer edge like lichen clinging to glass. Subtle. But there.Strange.

He blinked once, slowly, then narrowed his gaze — not out of alarm, but curiosity. Perhaps it was the atmosphere. The spectrum of station lighting skewed the visual field sometimes. Or the recycled air — slightly drier than Rheunon’s mist-dense circulation — could be playing tricks with his ocular membrane.

Still, he couldn’t recall seeing that tint before.

And Ax did not often fail to notice things.

Before he could dwell on it, the intercom system chimed again — the same soft sequence of tones, followed by the station’s calm, impersonal voice.

“The final meal of the cycle is now prepared.”

The words lingered a moment, suspended in the quiet like condensation on glass, then faded back into silence.

Ax didn’t move right away. His gaze lingered in the mirror a few moments longer, as if the green around his irises might shift again if he looked away too quickly. But it didn’t. Just his own reflection. Unchanged, except not.

He stepped into the corridor and let the door seal behind him with a soft hydraulic whisper. The station’s lighting had dimmed further in accordance with late-cycle protocols — long strips of low amber lining the corridor floor, interspersed with glacial-blue beacons at each intersection. The air smelled faintly of sterilized metal and filtered vapor, absent of any scent specific enough to evoke place. It could’ve been anywhere.

Ax moved quietly, his boots making little sound against the paneling as he followed the mapped route to the mess hall — or what passed for one on the station. This would be his first official meeting with his exploratory companion, the one chosen by another moon to accompany him during the descent and initial study. It would take three cycles to reach the ninth moon. Long enough to require preparation. Too short for anyone to hide their temperament.

Better to get a head start.

He didn’t know who had been assigned to him. The names had been held until last cycle, and even then, only the delegation lead had seen the final pairings. That was standard — an old Commonwealth tactic for forcing neutrality at the outset of sensitive missions. Let familiarity come later, after impressions had already settled.Ax wasn’t nervous, exactly. But he hoped it wasn’t a Virellan.

Not out of disdain. Never that. He had studied their history extensively, spent years cataloging the layered myths of Mycandra and the ecclesiastical rise of the Hypharch’s fungal sovereignty. Virellia fascinated him. A moon that breathed in rot and exhaled reverence. A civilization built not on conquest or control, but on decomposition, communion, and return. Their philosophies were some of the most sophisticated in the system — symbiotic ethics, sensory diplomacy, the theology of stillness.He admired it, deeply.

He just couldn’t understand how anyone could live like that. The humidity. The scent of moss. The architecture that pulsed when touched. Entire cities grown from cultivated decay. Buildings that metabolized waste, filtered breath, and whispered hymns into tree-bone.

Fungi were fine. In theory.

But he had never met a Virellan who didn’t smell like sacred mulch. Or speak in riddles woven with spore metaphors and breath-patterns. The last time he had tried to interpret a rotchant, it had taken him two weeks to realize it was a eulogy for a living tree.

Comments (0)

See all