The rehearsal finally dragged past midnight. The moment God hit that hateful Esc key, the gray-robed figures, still in a daze, slowly started looking around, coming back to themselves. They scowled at familiar reality, tiredly peeling off their white electrode yarmulkes. They looked at those yarmulkes with disgust, flicking them away in irritation. During the game, they weren't thinking. They weren't even people. But they were still living organisms, and they were utterly exhausted.

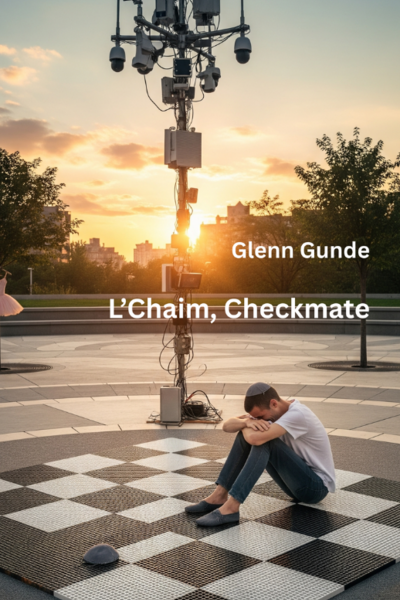

Once they semi-recovered, everyone just crumpled. Bodies crashed onto the tender tiles of the chessboard, tiles crammed with tiny lightbulbs and transistors. Some squares snapped out of the grid, getting all jumbled up. Good thing the audience had already cleared out; Yamin wisely kept the mind-control program humming until the spectators were gone. Only the staff, some reporters, and I remained.

That Esc key? Not just hateful. It deserved annihilation. Is there any moment more horrific than the moment of awareness? One keystroke, and thirty-two people became instantly miserable. Thoughts of yesterday, today, and tomorrow flooded thirty-two electrode-raped heads. Lying there, the robed figures slowly pulled their knees to their chests, hugged them tight, burying their faces in their laps. Their robes were hopelessly crumpled. Yamin was already on the phone, waking someone up to order thirty-two new robes for the next evening.

The sysadmin was collecting yarmulkes from the floor, prying them from under the curled-up robed bodies, stacking them in a special case. Rachel and another photographer circled, cameras clicking. It was like they were reporting from a warzone, a fresh battle just finished.

I noticed the robed figures were quietly trembling. They were sobbing silently, their tears watering the million wires and capacitors spilling from the chessboard. I squatted down among the living knots of humanity and put a hand on one’s shoulder. The knot aggressively shrugged me off, loudly whimpering, burrowing its head deeper into its knees. I looked at Yamin; the triumph was draining from his handsome face, replaced by shock. It wasn’t the first time I’d seen that look. Almost every one of Yamin’s performances ended up more destructive than expected. On the Graduation Day, those cursed mortarboards sent a few perfectly respectable ladies to the hospital with heart attacks.

“You knew this would happen,” I said, still squatting. Scattered black and white squares, wires poking out, lay all around me. The hall was quiet now; the journalists had gone.

“Glennie, not now,” Yamin rubbed his forehead in annoyance and started dismantling the equipment.

I waited a beat, but couldn’t resist. “Remember when we dreamed of making people happy?”

“Yeah, right, you’re saying everyone around you is just drowning in joy,” Yamin mumbled, flustered.

“That’s the thing, I’m having trouble with it myself. We’re not giving them what they ask for. We entertain them, offer fresh thoughts, emotions, but mostly, we’re just showing off our talents and inventions. What they need? Answers. We’re not giving them what they need.”

“What answers?! Give me one question that’ll matter for more than a week!”

“Why am I alive? That question matters for a lifetime.”

“Oh, really, Glenn Gunde, the scourge of philosophers! So what’s your answer?”

“Even just asking that question so it sounds meaningful… that’s a huge deal. People try to shove it away, you know, just to forget.”

Yamin cursed silently and went back to his gear.

A body near me stirred, uncurled, and sat up. Kind, sensitive eyes stared into mine. A young man, fluffy sideburns, shaved head. One cheek wet with tears. He spoke, holding my gaze with a death grip on his own. His voice was deep, soft, and inviting:

“Nature plays with us. Her game is more perfect than chess, and each of us in this game is like a white king. Victory is destined for everyone. Nature herself ordained it. She’s like… she’s playing black. And she’s playing white, too. Only white doesn’t see it that way. They think they’re making moves, eating black pieces, getting painful responses from them. White thinks they have strategies. But all strategies belong to nature. And they lead to white’s victory, just not the one they imagine. One day, the white king will gain consciousness and see that there are no enemies—no black pieces—only nature. And all along, from the very start of the game, every move, and all the moves together, were ingeniously arranged by nature to bring the white king to consciousness. But for now, the pieces move completely unconsciously.”

The young man stood, dusted himself off, grabbed his shoes from the floor, and stumbled erratically, tripping on the rough carpet, toward the exit. He vanished, pulling the door shut behind him.

“At least someone had an epiphany today,” I said to Tim, getting ready to leave myself.

“L'chaim,” Yamin replied, curt.

“L'chaim, exactly. We’ve been saying that word for two millennia, and it’s like we don’t care that there’s nothing behind it.”

“There used to be!” Yamin flared again, throwing his hands up sharply.

“We were different then. No argument there. We were united by a purpose, we knew it. And our neighbors, if they didn’t know, they guessed its significance. And if one of us said ‘L'chaim,’ they knew exactly what life they were talking about and why. We were conscious because we were united. The moment we fell apart, we forgot everything, and life started pummeling us from all sides. Still is. And we still keep saying ‘L'chaim.’ On holidays and weekdays.”

“Listen to you, the whole damn nation’s a bunch of idiots!”

“Not idiots. Just offline. Unconscious. Dragged by their egos to the corners of this planet. But the planet’s round! I think this word, like many other words, books, things, traditions—it’s national memory. A thread that will lead us back to love and harmony. Who knows, maybe we’ll unite, see the world while we’re still alive.”

“Alright, that’s enough of this verbal diarrhea. You’ve splattered my whole board!”

Another body stirred, then sat up. Something on the chessboard crunched beneath it.

A thin guy, delicate features, elongated shaved head, stared at the brick wall. He was breathing deeply, moving his hands from his knees to his ankles and back. Then he coughed, and through the cough, called Yamin by his last name a couple of times. When his throat settled, his voice was high and melodic. Very calm:

“Yamin, where do you live?” the guy asked, still staring at the wall.

“St Johns #2105,” Yamin answered automatically, prying white squares from beneath the reclining bodies.

“You don’t happen to have a live beer shop on your first floor, do you?”

“No.”

“Strange. Why does it pull me so much, then…” the young man said, stood, then fell. Picked up his shoes, stood again, and staggered out of the hall.

“Okay, Glennie, we’ll sort things out here. You coming tomorrow?”

“Where else would I go?!” We shook hands. I pulled on my jacket and left. Rachel was already sleeping waiting for me at the buffet.

Comments (0)

See all