They say destiny is a circle.

But some circles never close—they just spiral endlessly, like a whirlpool dragging the soul downward. Not to die, but to dissolve.

Nguyên, the Vietnamese younger brother—the one who once orchestrated the conspiracy, who once carved fate with a blade—began to dream strange dreams.

In his dreams, he sat on a throne of bamboo, in a grand hall filled with Westerners—all dressed in áo dài, eating fish sauce, calling him “Master,” “Ancestor,” “The Reviver of the Race.”

He smiled.

He thought it was victory.

He dreamed of standing atop a mountain, holding aloft a map: no more France, America, or Britain—only Vietnam, stretched across the globe.

He heard Vietnamese echo through European cathedrals, saw white children reading The Tale of Kiều instead of Andersen, saw Paris draped in red flags with yellow stars.

He called it “the dream of cultural revenge.”

But the deeper he dreamed, the more he lost his way.

One time, he pointed at a blonde child in his dream and said:

“You must call me Grandpa.”

The child smiled and replied, in a Vietnamese laced with French:

“But Grandpa... you’re my Grandma, aren’t you?”

That line sliced through his mind like a blade.

He woke drenched in sweat, vision blurring, as if the world around him was melting into a river—and in that river, the blood of East and West had mixed, indistinguishably.

Nguyên went searching for his sister.

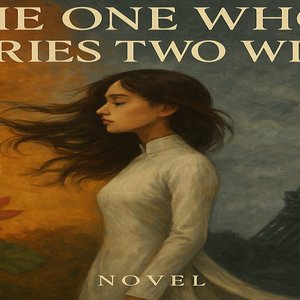

Linh—the woman who had once ordered injections, who once stole identities like pretty clothes.

He looked at her and asked:

“Are you still Vietnamese?”

She smiled—a smile he’d never seen before, half gentle, half frost.

“What do you think it means to be Vietnamese?”

“Someone who hasn’t been Westernized. Someone who preserves their roots.”

“And what are those roots?”

He fell silent.

“What our ancestors passed down,” he replied slowly.

“Blood. Language. Way of life...”

“Then tell me—did any ancestor ever marry a Westerner?”

That simple question left Nguyên speechless.

Then Linh said:

“You know… there are days I speak French more naturally than Vietnamese.

There are nights I dream of floating in lavender fields, not rice paddies.”

“So you’ve betrayed your people?”

“No,” she answered softly.

“I’ve only accepted the parts of me I can no longer deny.”

Nguyên stepped out of her house, hollow.

All the ideals he had clung to—purity, heritage, honor—began to crumble.

He went searching for the mixed-blood girl—the one he once called a disaster, a chaos.

An—no longer bearing that name—was living quietly in a small house, teaching orphaned children.

Children who didn’t know their parents.

Children who didn’t know whether their blood was “pure” or “mixed.”

He looked at her—the one who had once been his husband in a past life, now a girl with a fragmented soul.

She looked back at him.

Her gaze held no anger, no blame—only the deep stillness of a dried-up lake.

“Why are you here?” she asked.

“I… don’t know,” he answered honestly.

“You want to ask me who I am?” she gave a faint smile.

He nodded.

She pointed to the children learning to spell:

“They don’t know who they are either. But they live, they learn, they love.

Maybe… knowing who you are matters less than living like someone who knows how to love.”

He bowed his head.

For the first time, he felt small.

That night, he dreamed of standing before a mirror.

But it didn’t reflect him.

Instead, faces—male, female, white, yellow, ancient, modern—flashed across the glass, appearing and vanishing.

In the end, the mirror shattered.

And a voice echoed in his head:

“When blood is blended, no one is the host. No one is the guest.”

The next morning, he wrote a letter.

Not addressed to anyone.

Just left it on the table:

**“I once wanted to make the world a replica of myself.

But I never knew who I was.

I once hated the mixed.

But now I understand: mixing isn’t betrayal—it’s a form of survival.

I thought I was preserving identity.

But really, I was afraid—because I never truly understood my own.

Now, I seek no one to punish.

I only wish to learn how to listen.”**

No one saw Nguyên again.

Some say he secluded himself in the mountains.

Others claim he went to Africa to volunteer.

Cruel tongues whispered that he went mad, struck by “cultural confusion.”

But those who truly understood said nothing.

Because they knew: he wasn’t gone.

He had simply dissolved—like all the things he once tried to fight.

And the mixed-blood girl?

She still lived.

Still taught.

Still wandered the markets, wearing a French scarf and a nón lá.

Some days she wore an áo dài.

Other days, a vintage dress.

People didn’t know what to call her—he, she, madam, sir—so they called her the Nameless One.

She didn’t mind.

Because she knew:

Once you’ve gone beyond names, there’s nothing left to prove.

On the final night of the changing winds, she wrote one line in her journal:

“This isn’t the end.

But if it is a curse,

Let me be the one to repeat it—

So those who follow won’t have to.”

Comments (0)

See all