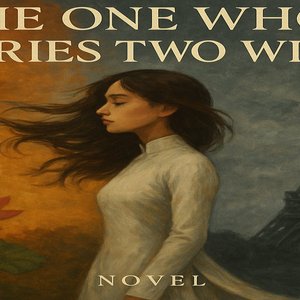

She walked out of her childhood like one emerging from a fire—smoke clinging to her skin, eyes red, hands trembling—but alive. And survival itself marked the beginning of a new journey: the journey of someone cast out, yet unwavering in preserving her dignity. Like a lotus blooming in the mire, needing no name to blossom.

Her secondary school years passed like an unending storm. She moved from one school to another, each bearing a different face but the same eyes—eyes filled with suspicion, judgment, and disdain.

At first, there were whispers:

“That mixed-blood girl is studying at our school?”

Then came scrutiny:

“Was she really assaulted? Or did she make it up for attention?”

Eventually, came punishment: her grades lowered despite correct answers; her responses dismissed because the teacher “didn’t like her attitude”; excluded from group work; beaten in places without security cameras; called “low-class mongrel” in the school corridors.

From prestigious French schools to international academies in Asia, the institutions formed a silent, subtle alliance—a network of rejection. No one said it aloud, but everyone understood: she was the hyphen no one wanted in their pure-blooded system.

Even her twin sister—once part of her very soul—turned away.

“You’ve shamed me,” her sister spat, eyes clouded with hate.

“I don’t want to be seen as having the same blood as you.”

But she didn’t cry.

She simply told herself:

“As long as I can graduate… that’s enough.”

And she did graduate.

Not with fanfare, but with blood and tears.

An international diploma—neither glittering nor prestigious like those awarded to the “pure” and privileged—but a testament to a silent rebellion.

They called her grades a failure. But they didn’t know they were forged through rigged scores, swapped exam papers, and nights of studying in tears out of fear of being expelled.

She never failed.

She was simply denied the right to succeed.

When college came—cruel in its irony—she was directly admitted into a medical school in Vietnam. But instead of accepting that safe haven, she returned to France—the very place that once stabbed her heart with prejudice.

No one understood why.

But she did.

Some wounds must be faced directly to ever close.

This time, college wasn’t a place of learning, but a prison named “international cooperation.” She was allowed to study—but only for two years. Allowed to stay—but tightly surveilled in the hospital. Allowed to live—but only as a research subject, a guinea pig for Franco-Vietnamese medical education experiments.

She once wanted to die.

Once stood atop the hospital roof, contemplating the fall—not from weakness, but from being too strong for too long.

Then COVID-19 struck.

The pandemic—tragic for the world—became her personal escape.

She returned to Vietnam, studied Psychology online. At the same time, she enrolled in a second bachelor’s program in Linguistics at an international university in Vietnam—still connected to the same system that had once rejected her.

Online learning—her supposed salvation—turned into another prison.

Teachers couldn’t see her face but still gave her low marks.

Excellent assignments couldn’t score above 7.

She had no friends. No allies. Only screens, cold presentations, and grades that slapped her efforts.

They said, “Everyone passes online classes.”

But when she graduated with two Bachelor's degrees and one Master’s, they sneered:

“Bought degrees? Who even checks those?”

They didn’t know:

Every presentation cut off mid-sentence due to dropped internet.

Every paper rewritten after software crashes.

Every night awake until 3 AM completing demanding academic requirements—done alone, by herself.

They said she lacked hands-on experience?

What about the volunteer hours?

The sessions with autistic children?

The home visits to the depressed—the ones no one else dared approach?

They said online degrees held no value in Vietnam?

Then what of her in-person Linguistics degree from a Vietnamese-certified international institution? Was that fake too?

What about the internationally accredited TESOL certificate from Australia, the Pedagogy certificate from Vietnam’s Ministry of Education, the French Psychology diploma, the 1240 SAT score, and a 7.0 IELTS?

Who sold her all those?

No one had an answer.

She chose to pursue a Doctorate—not to flaunt degrees, but to prove that online education is not a crime.

That real study, real effort, real failure—are all part of the process.

No one graduates just because they have money.

They once called her the bottom of society.

But they didn’t realize: sometimes, it is from the bottom that the strongest souls are born.

Lotuses do not bloom in palaces.

They bloom in mud.

Some said the lotus isn’t as beautiful as the rose.

But the lotus doesn’t need to be beautiful.

It only needs to live.

To live in silence. In loneliness. In obscurity.

And it is precisely from obscurity that the lotus blooms—radiant, for no one, for no applause.

She is that lotus.

And if you—the one reading this—consider yourself “normal,”

but do not have even a fraction of the effort, faith, or strength

as the one you once looked down upon as “abnormal”…

…then perhaps it is you who should be ashamed.

Because sometimes,

“normal” is just the mask worn by those too afraid to leave their comfort zones.

And she—she lived through everything the world hurled at her—

and still walked forward with pride,

like a curse that had been transformed into something sacred.

Comments (0)

See all