At my workplace, we’ve got this running joke. To design a bio-toilet, you gotta start with one simple question: Who’s the lavatory protecting—the person inside, or everyone outside? Someone’s gotta be protected, no matter what. Altruism is our company’s middle name.

Altruism and Deutschmarks. For three years now, every workday at 4 PM, I hit the shop next to the office. They sell cheese and soap. The cheese, I gotta say, is magnificent. Haven’t tried the soap. But I’m not there to blow those paper bills on cheese. At 4 PM, every day in that shop, I engage with the dialectics of music. Music’s always playing, and often, it’s actually good enough to justify the trip. But again, I’m not really listening. I’m asking myself: Why do my ears make my whole body move? All around me: the smells of soap, the smells of cheese, merging into some wonky, multi-colored brickwork. Whispers and chatter between customers and clerks, way less harmonious, vulgarly demanding way more attention than the music. The thud of the door and the tinkle of the bell, gently pulling out and rearranging all my internal organs. Gusts of wind from the fans and plant tendrils clinging to my shoulders, my fingers, my hair. The kaleidoscopic international discord of cheeses, laid out in the display case so the colored side stares you down, but the actual body of the cheese is only visible at an angle. My stomach’s doing somersaults. You can’t calmly look at that much cheese. And yet, I’m totally immersed in the music—and totally immersed in the dialectics. Am I a dreamer? Nah, I’ll leave the shop, grab lunch, and go to work, but this internal monologue? I need it like a ship needs a lifeboat.

Today, I did a terrible job pretending to carefully select cheese, and a shop employee actually spoke to me:

“Sir, did you come here to warm up?” I guess my outfit gave off a real Arctic vibe.

“I came here to ask you: Does music play in the bathroom at your home?” The girl wrinkled her nose, rubbed her sweater below her chest with her left wrist, and ducked behind the counter to wrap some Mozambican Parmesan. “Don’t think I water my plants with mercury; it was a professional curiosity.” A fat glob of mercury slid down a ceiling vine onto my shoulder, shattered on my tweed, and sprayed a fine, silvery buckshot everywhere, like from a devilish shotgun.

“Sir, are you buying anything?” It’s hard to refuse a girl like that. The door clinked shut—it was just me and her in the shop, plus the other employees hiding somewhere in the back.

“Wrap me up, please, some goat cheese with a wine rind.”

“How much?” the mercury-wounded lady asked, already slicing a thin piece from a burgundy cheese wheel and placing it on a torsion balance.

“Just enough to compose the Turkish March. Funny, isn’t it? This cheese combines both masculine and feminine principles.”

“How so?” The girl bent down to staple my package, and in my head, cymbals drowned out a gentle violin.

“Outside, it’s a goat; inside, it’s a she-goat, don’t you think?” She smiled, then somehow deflated, and asked for a sum of money that could feed me for an eternity. “Still, don’t be so deaf to me. I just brought your shop a day’s worth of revenue. Does music play in your bathroom?” I tucked the cheese behind my ear.

“If you played music in there, I’d go to my neighbor’s,” her anvil of a mouth replied.

“Well, then I’ll play in your neighbor’s bathroom.” The girl smiled again and again deflated. When I switched to dusting imaginary mercury off my shoulder, she dried up completely and quietly dictated:

“Write this down, but don’t tell anyone: 358-44-645-19-63. You’ll be in the same hospital as my aunt. She’s such a sweet woman! All the best, I’ll visit you.”

I walked out of the shop, a little wired from all the digits my wallet had shed, pulled the cheese from behind my ear, and bit into the dark-red cardboard with my white teeth.

“So, what were you saying about what you can do with the bio-toilet itself?”

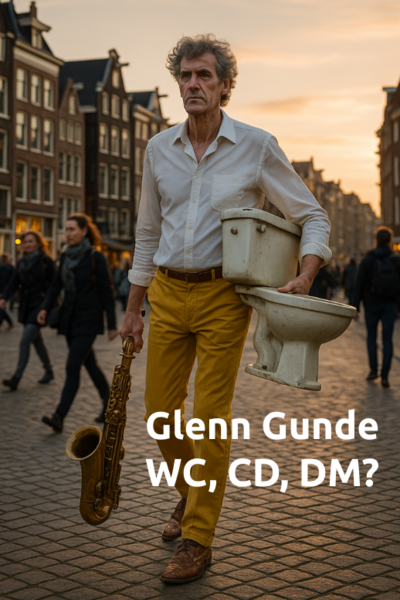

“Well, I realized I was wrong. Of course, I deal with weightless, bodiless things. And you—when’s your next concert?” The standard question for a musician when you’ve got nothing else. Dormshiganger scowled and spat out:

“Does it matter?” We were nearing the park, where the remnants of his toilet still lay scattered.

“I’d really love to see you perform again. Listen, my workplace could actually be part of your grand endeavor.”

“How so?” He pulled his imaginary mouthpiece from his cheek, without taking out the second one, blew through it, and put it back in his mouth.

“How about we build a stylish canopy over your toilet, maybe even shaped like a treble clef? Or we could wall it off—just need to clear it with the city. They won’t object, it’s music! And we’ll give you a discount.”

“Doesn’t make sense. I’m always changing my location anyway. Tomorrow, I’ll be composing music on the riverbank.” Some guys with Nazi symbols were fighting punks at the next intersection. Over a toilet, perhaps?

“Let’s walk a little faster. Either way, you can always reach out to me. Here’s my card.” Dormshiganger rubbed the card with his finger and, satisfied with the grid-like texture of the cardboard, painfully shoved it into his back pocket. “Have you ever played in a bathroom?”

“Let me think. Once, I ambushed a girl who’d dumped me. I accompanied the greatest of all her weekly deeds. The closer it got to finishing, the louder I played. It ended with a wild improvisation on the high notes. She just jumped up and flew out of the bathroom, forgetting to turn off the light. Probably ran to her neighbor’s. I was a terrible prankster back then. Tough times, you know, the Union hadn’t broken up yet.”

“Which Union?”

“Doesn’t matter. It just got in the way of making music, got in the way of everything.” Dormshiganger’s forehead crinkled into an accordion, and he let out a long, loud sigh.

“So that’s why you had to play in bathrooms?” Dormshiganger looked at me intently and squeaked something into his mouthpiece.

“Why did you ask me about playing in bathrooms?” He shrugged.

“Just, if you agreed to play for me again, only this time quietly and melodically, subtly, gently, like you do in between compositions. I’ll pay you the price of a full concert.”

“Play in your bathroom?” The musician’s face stretched, and the mouthpiece started to fall out of his mouth, but his teeth snatched it and pulled it back in.

“No, not in mine. To be honest, I haven’t even gotten the address yet, and it’s a whole adventure anyway. If you’re generally open to reliving the good old days, I’ll tell you later.”

“Hey, you selling salvia?” A red, white, and black dandy stood beside us.

“No,” we answered in canon. For some reason, they didn’t like Dormshiganger out of the two of us.

The cheese wasn’t in the bag. The slice was so thin, it was just wine. But the smell of goat was unbearable. Though, it probably wasn’t from the cheese.

Comments (0)

See all