I stepped into one of our bio-toilets. Gotta maintain appearances. And then it hit me. Not a thought, really—more like an unconscious habit: I didn’t touch a thing with my hands. Even the door, I opened it with my foot (I know how to do that tenderly, at least in our lavatories). Though, coming out, the handle whacked my kidneys pretty hard. Generally, lavatories are kidney service booths. I wiped my perfectly clean hands on the most inconspicuous part of my trousers. For ages, I couldn’t bring myself to fix a bent eyelash that was slicing into my eye, because it would mean touching my eyelids. A toilet is intangible because we want it to be intangible. We see our clean hands as dirty just because we stepped into a lavatory. But—we don’t remember the touch. We don’t grasp it, we just instinctively avoid our own hands. We figure everyone’s got the same quirk, right?

Music is tangible only as much as we want to touch it. Only as much as our movements are ecstatic when we dance. Sexy or innocent, we feel the music with our hips. Everyone’s got a subwoofer right there with them. A march of crowbars—we feel them drumming on the back of our heads. R&B and two-step—we feel someone leading us, gently, but with a firm grip. We figure everyone’s got the same rhythm.

I walked into the office, fumbled for the light switch—and everything exploded, sprayed, hissed. Then I hit the button on my desktop and got online. I sat in front of the monitor for a good hour, and finally, I managed to find the address I’d whisper to Dormshiganger—so quiet, so insidious, so expensive. Heading for the office exit, my eyes carved out a small memo hanging on the bathroom door: “Dear Employees! Don’t you think our bathroom is a bit grubby for a world-class toilet company? Management…”

Outside, something cotton-soft brushed my stomach and whisked away to the next toilet. Yeah, a person’s whole life is a rush—a rush from one toilet to the next. That’s the only reason we get mad at each other, cut people off, lose our driver licenses for fifteen months, curse, strike strange poses. We figure everyone’s stuck in the same race.

I looked for the toilet in the park, looked by the riverbank… Dormshiganger was gone.

“Oh, if you want to know the price of my concert, I charge seven thousand for a ninety-minute performance.” God, that’s more than a slice of cheese! He turned his wide face to me, and his features became streamlined and utterly convincing. The mouthpiece pressed, mentally, against my chin.

“Well, I don’t need it that long.” Maybe before the Union fell apart, three-hour bathroom gigs were the norm, but we live in a dynamic society now. “Twenty minutes.”

“Fine. I like you. I’ll give you a 50% discount.” He whistled into his mouthpiece and paused to wipe it slightly, catching the sun on the metal.

“That’s… uh… eight hundred?” Dormshiganger looked at me closely, even closer. Closer than ever before. Then he took a step, and we started picking up speed again. The two of us, spinning this planet, discussing money.

“Three and a half,” we were almost running. Setting records for race walking. I was doing division in my head. I couldn’t get to three thousand five hundred. It all pointed to me owing him twelve thousand six hundred for fifty minutes of playing. “Three and a half, and I’ll gladly play in the bathroom.”

Finally, we reached the only open entrance hall on the entire avenue. I darted in, Dormshiganger right behind me. I guess I turned too sharply; Dormshiganger’s tall nose smacked into my forehead, and he spent the rest of our meeting pinching his bleeding nose, breathing through his invisible mouthpiece. The alleyway was dark and smelled of cold marble, just like a useless business club. The stone slabs on the floor were cracked, looking like they were layered on top of each other, slowly fighting their mineral battle, slowly memorizing the history of the place they lay, so that it too would crack and grow like a mineral.

I whispered the address to the musician. He asked me at full volume how to get into the apartment. I whispered back, so quietly he read my cracked lips. Learning the time, Dormshiganger almost shouted: Three thousand!

“What!”

“Yes, my dear friend, I’m giving you another discount. Three thousand is the final price.” For a couple of moments, I stared at one of the slabs, wondering how to lift it. I had two options: bury my companion under it, or find three thousand there. “So, have you decided?” I wrote a check. “You didn’t put a zero at the end.” I took the check again and, after “300,” wrote a massive, utterly disproportionate “0.” Dormshiganger smiled with satisfaction, two rivulets of blood trickling onto his upper lip, and squeaking his mouthpiece in a swing style, he disappeared.

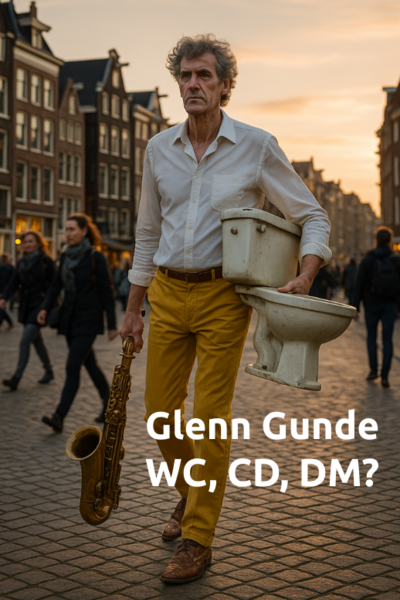

I disappeared too. I even saw two cars bounce on open manholes, colliding head-on, hiding Dormshiganger’s tall figure from me. He's a lot like a saxophone, turns out. Maybe he holds the imaginary mouthpiece the wrong way, not the way he’d hold a real one. Maybe it’s an illusory entrance to Dormshiganger’s equally illusory, wonderful musical inner world. A saxophone-man.

Yes, we’ll do it. The idea might seem crazy, but I’ve made up my mind. I’ll arrange everything. The girl told me if I played in her bathroom, she’d run to her neighbor’s. Fine, so be it! We’ll play in two bathrooms at once. Decided. I want to watch her reaction. It’ll be fun. And harmless enough. People love harmless jokes, they love it when you put a banana peel under their feet, and then it turns out to be dried. We figure everyone’s into that.

Dormshiganger—no, he’s not like a musical instrument. He’s like music itself. Not in every way. But that one peculiarity of his: he seems material, yet instantly elusive, uncontrollable. Just like music, he’s tangible only as much as we want to touch him. To feel his snorting breath in the wrinkles of our forehead.

Passing the cheese-and-soap shop, my mind already on the thinly squeaking door of our business center, dressed in a light summer shirt, I felt a cold blast on my stomach and a warm, rustling one on my chest. Cotton and silk. My face expected something hot when I saw the Spanish lady in my hands. But she started talking quickly, and as I turned 180 degrees with her to keep going, she spoke even faster, and in her voice, I recognized a familiar undertone, like a babbling brook or stirred sea sand at the bottom. Her black eyes were already merging with her magnificent wavy hair in my vision, and she was still standing where I’d left her. Flying into the office, I sat at my desk and spent half an hour with my head in my hands.

“It’s seven already, office is closing. You almost done?” The CEO’s secretary.

“Oh, right? Okay, I’ll finish tomorrow.” I caught her gaze, which perfectly understood I had nothing to finish tomorrow, grabbed my briefcase, and pushed away from the desk, my heavy, accidental boot almost tearing its leg off. “Damn it.”

“You’re out of it. Want to take a vacation?” The secretary looked at me trustingly and condescendingly, as if she were both my daughter and my mother at once.

“Nah, it’ll pass soon.” The elevator let us out on the ground floor. Reaching her car, she turned to me and unequivocally offered her cheek. I stood there, swaying slightly from an imaginary wind, remembering those lines from the Bible about cheeks. After standing like that for two seconds, I finally said: “Cheese.”

And a moment later:

“Fooled me.”

“You just need a break. Pack your bags right now, and don’t let anyone see you in the office for a month. Fly somewhere, Argentina or New Zealand. Sometimes it helps to flip yourself over so everything inside settles, you know?”

A shaker-man.

Why do I always avoid kisses on the cheek? Probably some phobia that developed in early childhood. Maybe it’s my mother, who kissed me on the cheek every night until I was five or six, and since then, for a very long time, all I remember is her hitting me and pulling my hair. And the secretary is beautiful.

She flashed her gorgeous legs, slid easily into the car seat, and coolly rolled out of the parking lot. To spite the whole world, I drove as slowly as possible. 15 km/h. At the very first intersection, I was stopped and checked for alcohol.

“Sir, you have a fast car. Drive normally, don’t torment my colleagues.” The slender uniform turned its most flattering side to me and moved slowly but confidently across the double solid line, just like the strange heroines of some delirious stories. Only those walk disheveled and barefoot.

Comments (0)

See all