The two girls’ hands moved lower down my limbs. Linda breathed loudly with delight, massaging my legs. Pendeja was still a chest to me. Her hands—separate. Her hands moved over my arms, over my chest. She was much gentler than she’d first seemed.

Then I heard Sappho’s footsteps. She was getting closer. I knew. I saw without eyes: she was wearing only shoes! And N.O.T.H.I.N.G. else. She was first. She was first!

She squatted in front of me, pushing the table aside. The bottle where whiskey or tea with a kick had been fell to the floor and shattered. What would happen! What would happen now… She touched me too. Six hands. Six tender palms, thirty nimble, loving fingers. Oh, what would happen now!

She caressed my legs, Pendeja—my neck and shoulders, Linda—I felt her—her, my star—she took my hands—and… all three of them. Simultaneously. Synchronously. Oh my God! They pulled in different directions.

On my arms, on my legs, on my neck, on my chest, on my stomach—everywhere—tight ropes tightened. My stomach was meticulously wrapped in duct tape. My legs were tied in two places and tightly pulled to the seat, and in three places each—to the chair legs. My arms stretched along its back legs. An improvised leash hung around my neck. I was completely immobilized. The bosom disappeared from my face, and I saw the world as it was.

Sappho was dressed.

I looked at all three girls. They looked tired, but proud. There was no question of any kinky sex. They pushed the chair with me back, Pendeja took the leash in her hand and sat at the head of the table, Sappho and Linda sat too. Sappho, disheveled and magnificent, with a sincere, innocent smile, pried open my teeth and slammed them shut with such force that sparks flew from my eyes. She really knows how to brutalize men! To skin men alive.

“What do you want from me?”

“Oh, nothing. We owe the zoo, don’t we, Pende?”

“That’s right, darling! What do you say, Lin?”

“What you forgot: the guy screwed up. Pende, maybe I’ll run to the kitchen for some vinegar?” Linda stood up and looked at me like a seasoned cook eyeing a seasoned pig. In a friendly way. It’s just vinegar, buddy, her eyes said.

As she passed the hallway, looking across the street at the roof where my blood had already dried, I heard a strange sound. It was like a dull thud, mixed with a wet smack and a deep inhale. Something broke.

Dead Linda collapsed onto the hallway floor, more and more blood pouring from her head. The impact of bones cracked the laminate flooring. Her meaningless eyes stared directly into mine. Her beautiful legs lay splayed, making it both horrifying and comical. Her hair was strangely matted, a skull fragment lay ten centimeters from her head in a river of blood.

I instinctively yanked my arms to cover my face, but my hands didn’t move; instead, a sharp, radial pain shot through them. The leash tightened, Pendeja clutched her head and leaned back in her chair, unable to do anything more in her stupor. Horror and despair were etched on her belly. She shuddered and let out a quiet shriek, something in Spanish. Sappho abruptly lowered her head and winced, pressing her hand with clenched fingers to her eyebrows. Then, as if scalded, she snapped her gaze up and stared at something around the corner of the wall, in the hallway itself, where Pendeja and I, for a number of reasons, couldn't look.

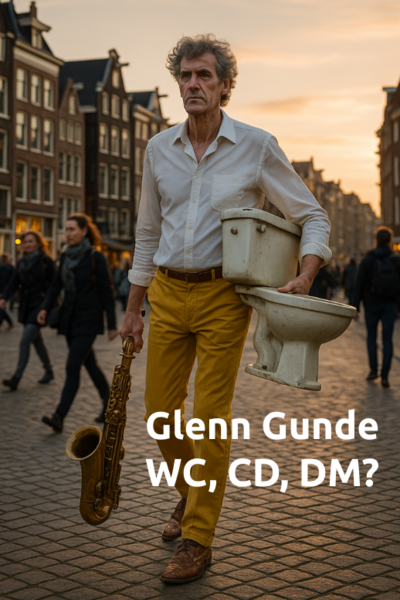

“The toilet, my dear, the toilet. It’s intangible, no matter what you do to it,” Dormshiganger’s voice gurgled. Something sloshed deep inside. He spoke slowly and inhaled deeply. “And music—it’s right here. Touch it, come here. Ah-ha, you can’t?” he noted, emerging from the hallway and stepping over the beautiful body. His entire white shirt was soaked with blood and grime. He dragged his left leg and clutched his heart with his right hand, nails torn off. In his left hand, he held a saxophone. Heavy, dented, without a mouthpiece. The bell of the instrument was bloody. Blood dripped from it, stretching into long threads. His face… his head…

It was a show all its own. Sometimes, driving on the highway, you see mangled cars suspended two meters high on the roadside. A warning to drivers. Dormshiganger’s head looked pretty much like that. Not to mention he was almost two meters tall. His forehead was like a bloody steak. His whole face was drenched; blood was still oozing from his forehead. Dormshiganger’s mouth was twisted, and many of his teeth were missing. His right ear was half torn off. Apparently, he’d made such a successful descent from six meters. Only to climb back up.

“You see, my dear manager? M.U.S.I.C.—here it is, music! Do you see it? And do you want to touch it? You liked this girl, didn’t you?” He looked meaningfully at Linda, bent down with a crack, lifted the hem of her flannel shirt, yanked it, sending buttons bouncing across the floor, critically examined what was hidden beneath, and then fastidiously covered the beautiful chest. After that, he continued approaching the ladies, who were quietly dissolving into hysterics, and me, bound hand and foot. I looked at the ladies with annoyance… the two remaining alive—and they, agreeing with me, exchanged guilty glances as much as was possible without turning their heads. Dormshiganger approached. His actions were unpredictable. In any case, we were all defenseless before him, before the deadest of the living in that room.

“And the Deutschmarks? Let’s assume we exchange them. Lenny? Is that your name?” Dormshiganger fumbled in his breast pocket for the three checks and pulled them out. “These red papers—their value is negligible, it was negligible even before all this happened, Lenny. Because my music is in my blood. My money is in my blood. Because my life hangs by a thread. Perhaps I have hours to live. Perhaps minutes.” He bowed his head and desperately squeezed his eyebrows. With a heavy sigh, he continued:

“Music—in the bathroom! How dramatic, right? No one has ever come up with that, Lenny. And you think that makes you great? Does it do you any honor at all? You’re a rare nothing. All you can do is offer to build a lavatory around the toilet on which I compose music. Your hands are dirty, but your mind is even dirtier. You won’t bat an eye—and you’ll hoard all the world’s cultural heritage in a giant lavatory. That’s your style. And you’ll pay for it with these red papers,” Dormshiganger exhaled the last word. Then he came over to me and, carefully measuring, slapped all three checks, soggy with blood, onto my forehead. Pendeja pressed herself against the wall, rocking back in her chair, staring blankly at Dormshiganger, at his shoulder. Glancing towards the hallway where a mirror hung around the corner, he hoarsely said: “Now you and I even resemble each other somewhat.” With a smirk, he walked around the table with the gait of an artist stepping away from an easel and stood right next to Sappho. She flinched and stared straight ahead. I looked at the leash that Pendeja still clutched in her hand. Her face was a grimace of a smirk superimposed on the disgust that hadn’t yet faded. She was looking at my forehead, where four and a half thousand tugriks dissolved, money that neither the toilets, nor the music, nor I, nor he had lost. Non-existent, fabricated four and a half thousand. Fabricated and, for good measure, drenched in blood.

“Lenny, do you know why I killed this girl? For three reasons. First, I have nothing to lose. Second, wasn't all this because of her? Did she provoke it?” I eagerly nodded my head, but then realized I was agreeing too soon. “Wait, my dear rag-man! We haven't gotten to the main point yet: I wanted to see your reaction. Of course, I wasn't prepared for you to be so immobilized. But I expected to see some reaction. Otherwise, why the hell did you bother with such an operation involving these miserable bathrooms! You felt nothing. Don’t try to make excuses, Lenny! I saw everything. This girl didn’t interest you one bit. You did this for some other reason. And the last thing I want to know in this life—why the hell did you start all this!” He slammed the saxophone onto the table with a crash, making the ladies jump, Sappho nearly falling off her chair, and the leash tightening even more around my neck.

“There’s something to it. The toilet is intangible. People who live by the toilet feel nothing. They don’t feel themselves, Lenny. This applies to you first and foremost. But you know how I feel music! You saw me compose it. I track changes in sound vibrations. Vibrations of metal in a chain and vibrations of fabric in a shoelace. Vibrations of skin—the most sensitive skin, disposed on the acoustically ideal inner surface of a toilet bowl. You don’t understand what I’m telling you, Lenny. But I feel music, I T.O.U.C.H. it, my friend.”

He tried to grind his teeth, but there were so few left in his mouth that instead of a grind, there was a crunch, and a couple of seconds later, Dormshiganger, covering his face with his elbow and grimacing in pain, spat out a piece of tooth. He looked at the ladies:

“Girls! The hostess has left,” he shook his head instructively and glanced at Linda’s body, “there’s no point in you staying here. Get out!” Dormshiganger took the saxophone in his hand again by the upper part. The girls began to rise unsteadily. Pendeja let go of the rope, and I looked at her pitifully. It was hard to breathe—the loop had tightened so much. I didn’t dare ask her to loosen the rope. She approached Dormshiganger closely, stared into his eyes, and braced her fists on her hips, arching her back slightly and leaning away. Her right elbow pressed into Sappho’s back, who stared at me bewildered, her lips slightly pouting, lips I loved more and more. God, I can’t stop thinking about the opposite sex for a second! I’m a lost cause, Dormshiganger just proved it.

Pendeja took a deep breath and spat with all her might into the musician’s face:

“Freak!” Her rolling Spanish ‘r’ turned into a sob, and she froze again. In response, Dormshiganger swung the saxophone like a fencer; it made an uneven circle and slammed the sharp edge of its bell into Pendeja’s stomach. It ripped open her black blouse like a soap bubble, it tore her skin like a soap bubble and plowed through the girl’s abdominal cavity from bottom to top, turning everything inside out and releasing her internal organs. The saxophone stopped somewhere in her lungs, breaking several ribs like matchsticks.

Music is tangible. So tangible that it would hurt you to learn it any other way.

Dormshiganger violently tore his instrument from the body, and Pendeja’s remains, perfectly whole and alive five seconds ago, flowed onto the floor behind Sappho’s chair. The girl didn’t see what happened. She just walked away. Not noticing a thing. As if by accident, she nudged the table with her feet, which pinned me to the back of the chair, and with a fast, robotic gait, head tilted and fists clenched, she left. I heard her apartment door slam: “Just try to break in!”

“Well, Lenny, I guess we can say the operation was a success, right?” Dormshiganger tried to smile—and he managed it. “Everything was great, a shame about the mess, of course, but it was a bathroom outing, after all. And the checks—well, you’ll write a new one, huh? Only for six thousand, because I’ll have to buy a new instrument,” he lifted the saxophone with two fingers and critically examined it. Then he put it to his lips, pressed some keys, took a deep breath—and unleashed a dizzying solo.

“Dormshiganger, that’s magnificent! Like a rollercoaster—what a solo!”

“No, Lenny, it’s all wrong. The instrument’s ruined, what can I say! Trash. But you, I see, you’ve got a weight off your chest. Scared, were you?”

“You know, just a tiny bit. You really entertained me today,” my lips trembled, and though for some reason I was sure the danger was gone, after everything that had happened, I was beside myself. My lips went numb. I laughed foolishly, out of sync, my voice cracked, I blinked erratically. Truth be told, I was happy. But in his terrifying monologue, Dormshiganger was right about something: I truly felt nothing—no pity, no horror at the sight of him killing the ladies. This brutality was a test, a lesson for me. Now Dormshiganger and I were friends again, we could walk the city streets and chat again! So it seemed to me, that was my perception.

“Yes, my dear friend.” Dormshiganger leaned on the table with his long arms, his long musical fingers splayed. He hung heavily on his straightened arms, and his face regained a menacing expression. “You’re a complete idiot, Lenny. You believe the latest nonsense, you wouldn’t bat an eye if someone told you, say, some long-lived woman from Belarus executed Osama bin Laden in the Amazon rainforests. You’d run around to your acquaintances in calf-like delight, call all your friends, and rejoice at the villain’s demise. I should execute you, yes, you, Lenny, but I don’t have time for it. If that girl isn’t a complete fool, the police will be here very soon. So I suppose I’ll go. Don’t try to find me, Lenny. You couldn’t even find me in your own office building. Let the police take you. They’ll like you. You’re somewhat similar to them. And I, well, maybe I’ll live a little longer. Tschüss!” Before turning away from me, with a flick of his hand, he returned the table to its normal position.

Dormshiganger spun sharply on his creaking, bloodied boots and vanished into the night city, taking his antique with him.

Comments (0)

See all