Helsinki

The night before July 4th wasn't just free; it was feverishly free. A solid, warm cuff grabbed me and Betty Lou and, with a stubborn, aggressive head-tilt, dragged us across the city. It was all happening too fast, too final.

That feverish freedom came from a lack of purpose. Without a destination, freedom felt like a wasted asset, and our reluctance to accept that made us curious about everything. We’d peer into every doorway, every face, start every conversation, then drop it just as quickly. We photographed everything, hoping to salvage something—anything—from the night.

We tore through the city, from Kaivopuisto to Sinebrychoff Park, Esplanadi to Tervasaari, Juttutupa to Kaisaniemi. We even sprinted down Aleksanterinkatu at an unnatural speed. Words were running short, albeit too plentiful. As we neared Stockmann, Betty Lou seemed more uninteresting than usual—her messy hair and shallow nature weren't helping.

Aleksanterinkatu ended. We dashed across the tram tracks, which felt as soft as juicy grass, and jumped onto the cobblestones by the mall entrance. I figured I had nothing to lose and pinned Betty Lou against the space between two display windows. I totally forgot that if she misunderstood, I’d be stuck feeling like an idiot for our entire visit to Chicago the next day.

When I got close enough that a misunderstanding was basically impossible, Betty Lou predictably turned her head away to the left. I hesitated, begging the heavens for a clue on what to do. The crowd flowed past us, guiltily looking down and arrogantly perked up all at once. My beloved, familiar people—useless and as helpless as me, all the same in their variety. I was listening to every rustle of their shoes, every breath, every word spoken out of necessity, hoping for a hint. I could hear Betty Lou’s breathing and knew I wasn’t responsible for its rhythm, but I was about to be responsible for it anyway, right now. My senses were on full alert.

"Where's the anvil?!" Betty Lou shrieked.

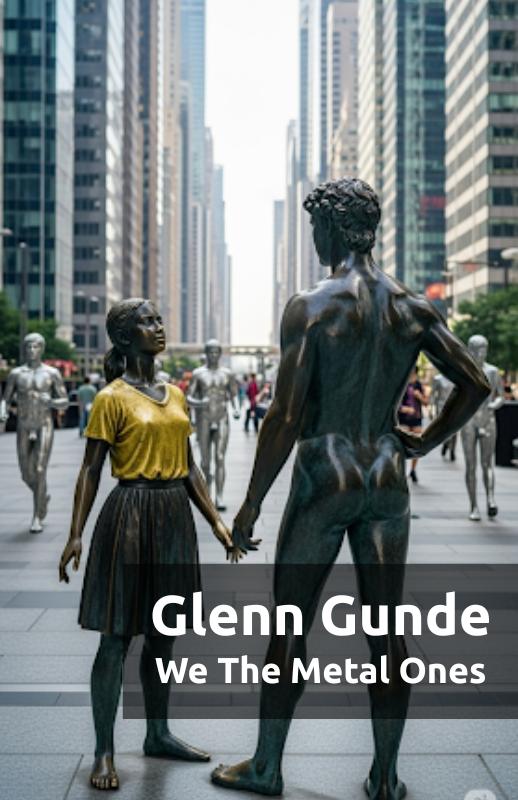

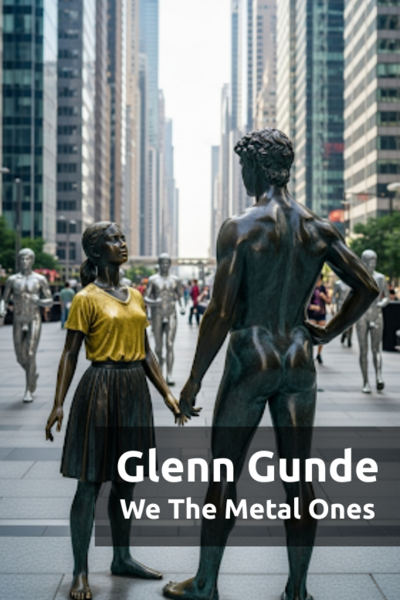

The phrase was completely out of context, but it simultaneously saved me and offended me. For a second, I thought she was talking about me, since I felt like I was caught between a hammer and an anvil. I pulled my scorched hands off Betty Lou's hips, straightened up, and looked where she was looking. The anvil was actually missing. On the corner opposite Stockmann, three huge, dark, naked men were posed in strange positions on a granite pedestal. Their skin dimly reflected the streetlights on Mannerheimintie.

The one closest to us was frozen in the middle of a disco dance, on springy legs, coyly waving both hands to his right. The second man, facing us, looked like he was about to put a bag in an overhead compartment on a plane, all sullen and focused. He was gauging the force needed to slam the compartment shut and staring irritably at the “no smoking” sign on the ceiling—as if that sign would ever turn off. Or maybe it was the same man as the first, just from a different moment in time. A third man, standing sideways to us, had his right hand raised and his left hand down, like he was doing morning exercises. He seemed to be telling his bronze buddies that the path to happiness wasn't in dancing or deep thought, but in a solid routine. All three were facing the center of the circle, shamelessly showing off their genitals to each other and everyone else. What they didn’t have was the anvil that was supposed to be in the middle of the circle. And they were missing the hammers that had always been in their hands.

A thought shot through my mind: The first man was my present, the second was my future, the third was my inner voice, and the missing pieces were what my inner voice would tell me tomorrow. In case…

---

The meaningless night was just about to find its meaning with all these revelations, but Betty Lou pulled me back into a swamp of empty chatter. We spent the rest of the night staring at the metal men and later, discussing them on the way to Kamppi, where my car was parked. Betty Lou was convinced from the start that the men were a sign just for us. "How can it not be for us?" she insisted. "Look, the streets are packed, but nobody cares that the anvil is gone! Everyone's just walking around like normal, and they'd walk past for a thousand years without a second thought about that anvil!". I was ready to agree that the indifference of my beloved, familiar people was unnerving, but mostly it was just depressing, since it was so common and ordinary in all its manifestations.

We never reached an agreement, and my hands never went back to Betty Lou’s hips. I stared blankly ahead, turned up YLE Radio 1, and started the car. We were driving out of the reluctantly sleeping city, ignoring the night's impressions just as we ignored the news on the radio. The news, frankly, made me want to leave this world, and especially not go to the USA.

Comments (0)

See all