Chicago

Our meeting with the representatives from the Agency for Technological Integration was scheduled for noon, so we had some time to kill at Columbia Bookstore. Betty Lou headed to the business section while I wandered through the large but cramped store, looking for something interesting. Maybe fifteen minutes passed. Finally, Betty Lou grabbed my arm and said she was ready to go, just as my eyes landed on a Finnish copy of Walter Laqueur's "The Last Days of Europe". I grabbed the book without thinking, and we left with a dozen useless business books to get an Oat Milk Horchata at Yolk.

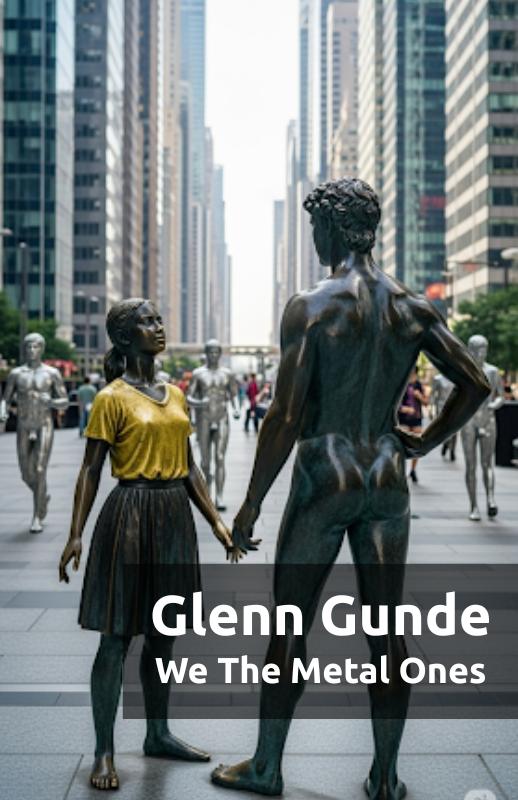

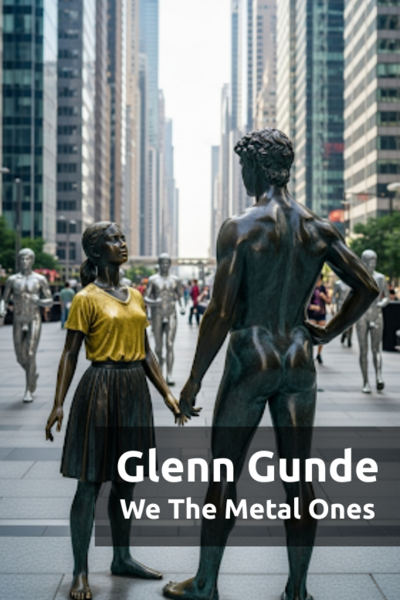

At the cafe, we read the back covers of all the books we’d bought. Betty Lou then handed me the honor of arranging the books in the cramped bag. I was busy with this as we were leaving the cafe and walking into the noisy, festive street. I definitely would have bumped into someone if Betty Lou hadn't nudged me with her elbow, stopping me next to a bus stop. She pointed diagonally across the street into the park. Over the young trees, massive metal heads loomed.

They were hollow in the back, facing in different directions, and their faces clearly complied with the diversity and inclusion policy. "There were about a hundred of these men, all moving like Brownian particles on a tight field of concrete plates near the edge of the park, staring into the space between them. You could see some of their hands. One looked like he was holding an imaginary camera, photographing the skyscrapers. Another was dancing, another was speaking at a rally, and someone else had his hands up as if surrendering. Other hands, however, were raised in defiance, fists huge and out of proportion, signaling a readiness to fight. A few had their arms hanging down.

In their lost expressions and mismatched poses, they resembled the men we’d seen in Helsinki, only their hair was shorter, their bodies younger, and their faces plainer. "Are you going to tell me we're the only ones who can see this, too?" Betty Lou asked me. The pedestrians went about their business, lost in their usual search for meaning. Buses crept quietly, on tiptoe, down Michigan Avenue, in a hurry to get away from the bizarre metal gathering and disappear behind Roosevelt Road. The only people who paid any attention to the metal men were Japanese tourists. They were happily taking photos, meticulously posing next to each of the 106 men with improbably wide smiles.

"But we saw them there, at the airport…", - I said.

"So what, Lenny? Everyone else at the border could have been seeing something else too!". "Maybe we just don’t read enough newspapers! Maybe everyone knows, and we're just now seeing it!".

"The people who read too many newspapers are the ones who don't know anything!" said Betty Lou, who only read business books, a hint of hurt in her voice.

---

The negotiations were tense, a total contrast to the cozy atmosphere of the Lowcountry South Loop restaurant. Our American partners told us they couldn’t expand their collaboration into Finland because the prospects for the Finnish market were "unclear" and the trade deficit was "excessive". The Agency Director spoke like a prophet, saying that the government was once again tightening its grip, using the most sophisticated and socially dangerous methods of economic warfare.

Thanks to a boom in information technology, a larger presence of European businesses on American platforms, and a rise in political awareness among Americans, the government was forced to use harsher methods to control the flow of resources and money than they did in the "good old days" of USAID. Before, it was enough to slap a business with thousands of regulations, punish them for non-compliance, and, if they got too uppity, accuse them of a lack of inclusivity. Now they had to be more unpredictable and situational, even shutting down disloyal publishers and raising the younger generation to be loyal to a great America. More blood, more cynicism, more uncompromising—especially toward foreign capital. In this kind of uncertainty, any collaboration in high-tech wasn't just risky, it was dangerous.

"What our country needs right now isn't all your high-tech stuff, but good old traditional tools, like a workbench and a hand plane," he said. "As for your ideas on exporting from the US, we were really excited by some of them. Let's move on to those".

The talks got a little easier after that. Almost all our ideas for products that could be launched and sold quickly in Europe looked promising to the Americans. But Jake, the director of the Agency, still managed to throw me for a loop. When the women left to check out which battered shrimp they could order with the least damage to their figures, he shared his other thoughts with me.

"I don't think we have more than a year to bring any developments to the European market—after that, there just won't be any demand," he said. "You, Lenny, might say I'm judging from an American perspective, one that doesn't know much about Europe, but I think America's problems are nothing compared to Europe's. Our problems are mostly about development, which is something we don't necessarily need, and more importantly, they’re familiar. Europe, on the other hand, is facing a brand new kind of trouble. I wish America could become Russia! They have what we're missing!".

"We can discuss any area of cooperation, not just innovation," I offered ironically.

"No, what we’re missing isn't for sale," Jake countered, not even cracking a smile at my joke. "I wish we could have a magical trade: we give them the rule of law and a working judicial system, and they give us the ability to not ask so many questions!".

"What questions don't you want to ask?" - I asked.

"There's one question that's eating us alive," he said. "It is the reason why we jump off roofs, shoot our colleagues, drink ourselves to death, lose our minds, go on antidepressants, give birth to handicapped children, and raise delinquents. It’s the question of the meaning of life. It’s this bitter, unbearable despair lodged in our throats. If I didn't distract myself with work and thoughts of a high-tech future, I would've splattered my brains all over the wall a long time ago…”

He continued: “The problem is, the more acute the lack of meaning becomes, the less interest there is in innovation. You start to wonder: what’s the point of it all? OK, so we save another minute a day with some machine. If we’re lucky, we invent a new distraction to keep our minds off the heavy stuff. It's not like we can just drink whiskey all the time! But while we're distracting ourselves from this question, it's not going away. It's growing!"

Just then, the women came back, and we spent another hour going over documents and plans.

Comments (0)

See all