Nadelaguram Street PT.01

Oct 13, 2025

Creator

Recommendation for you

-

Recommendation

The Sum of our Parts

BL 8.8k likes

-

Recommendation

Arna (GL)

Fantasy 5.6k likes

-

Recommendation

Blood Moon

BL 47.9k likes

-

Recommendation

Earthwitch (The Voidgod Ascendency Book 1)

Fantasy 3k likes

-

Recommendation

What Makes a Monster

BL 76.6k likes

-

Recommendation

For the Light

GL 19.1k likes

-

Feeling lucky

Random series you may like

203.4k views28 subscribers

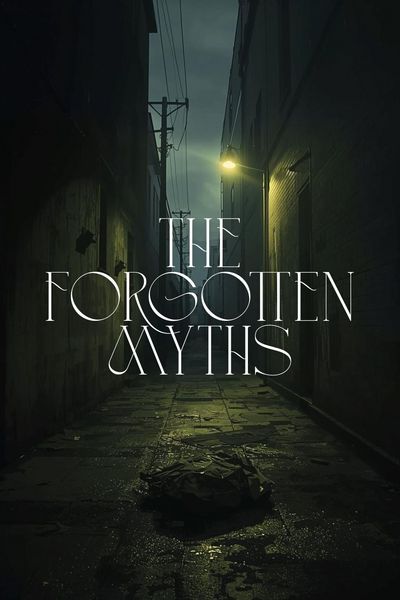

Each tale in Those Forgotten Legends stands alone, yet together they map a hidden world beneath ours—a city of echoes, secrets, and unanswered prayers.

Told as self-contained narratives written in vivid realism and quiet dread, these stories blur the line between rumor and record, between what is lost and what refuses to stay buried.

Some legends fade. These remember you.

Comments (0)

See all