*NOTE: The following story is a work of historical fiction. While based on some real historical events, it includes fictional characters and fictionalized occurences. Its intent is to entertain and pique the reader's interest in the history involved, not to teach about the actual events referenced. It includes themes that some may find upsetting and is recommended to readers 13+

Written and illustrated by Hannah Bottenberg Lee

Prologue

Buchenwald

Concentration Camp

December, 1944

Snow falls languidly from the grey sky, drifting in slow, swirling winds to blanket the earth below. The soft hills of the surrounding land are peppered generously with a smattering of trees: beeches in the front and further back, the pointed tops of pines. The natural landscape is contrasted sharply by a collection of stark, man-made forms. An imposing, electrified fence topped with barbed wire. Many long, plain buildings darkened by the clouded sky.

Behind the fence, a group of prisoners clad in threadbare, striped uniforms shovels a path through the snow. It is work designed to break the spirit, not to serve any practical purpose. The snow will only blow in more drifts, and then those too will need to be shoveled away: a never-ending exercise in tedium until exhaustion or frostbite arrive.

A short distance from the prisoners, two SS guards stand watch over them, huddled close, shivering still in their thick, double-breasted jackets. One guard is tall with icy blue eyes and white-blond hair, his default expression one of smug indifference to the world around him. The other is shorter, with dark hair and tired, drooping eyes. They are both clad in dark uniforms, the ominous white skull of the Totenkopfverbände standing out on their collars.

“Have you heard the news from the Western Front?” the taller guard asks, making mindless conversation.

“What is that?”

“The American lines in Belgium are holding. I don’t have a good feeling about it.”

Rolling his eyes slightly, the short guard takes a drag on his cigarette. “Nonsense!” he scoffs. “Those stupid Americans won’t stand a chance against us. Why must you be so negative all the time?”

“I’m not being negative. I’m simply being realistic.”

Then the tall guard notices something — a lack of movement amongst the prisoners. As the rest of the emaciated, shivering men continue their shoveling, one falters and slumps over his shovel. He is really more of a boy than a man, though it’s hard to tell with his shaved head and sunken eyes.

“Hey!” the tall guard calls to him. “Get back to your work!”

There is no response from the boy — only stillness as he lies dangling over his shovel perched in the snow.

The tall guard stomps towards him, rifle in hand, boots crunching furiously through the ice.

“Get up!” He nudges the boy with the butt of his rifle.

No movement.

“Get up,” he shouts a little louder this time, “you useless, little Schweinehund!”

The tall guard frowns as he strikes the unresponsive boy three times — hard — upon the shoulder with the butt of his rifle. With the second whack, the boy regains awareness. He cries in pain, which does nothing to sway his assailant.

“Leave the boy alone!”

The shout echoes through the surrounding area. A pall falls over the prisoners and their work slows. Many of them glance shiftily at one another, wondering who among them would dare to demand such a thing. The tall guard, silenced by outrage, looks over to the source of the voice.

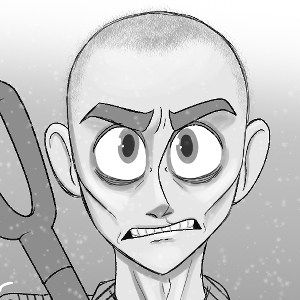

The young man stands firmly, his shovel in hand, shaking not only from the cold, but the anger he feels at the injustice of the situation. Much like the boy, his starved features betray his youth — but there is a fire of fierce determination in his deep-set green eyes.

The tall guard sneers at him. “What did you just say?”

“I said: leave the boy alone! You haven’t even given him the chance to right himself.”

The short guard, trembling with anxiety, aims his rifle at the young man. “Take one more step and I’ll drop you like the pile of Scheiße you are!”

As the short guard continues to keep the young man in his sights, the tall guard steps forward. He smirks, a malicious glint in his pale eyes. “You haven’t been here very long,” he says, towering over the prisoner as he looks down on him like he’s nothing more than an insect. “I’ll spare you this time — but if you ever speak to me that way again, you will be shot. Am I understood?”

The prisoner glares back at him, that defiance still plastered on his face. “Yes, sir.”

“Good.” The guard raises his rifle and strikes the man in the stomach. He crumples to the ground, sputtering for the breath which has just left him. The boy, now kneeling propped against his shovel, watches as the guard stomps on the man who just stood up for him, his dark eyes wide with horror.

* * *

Later, long after the sun has set, the boy makes his way through the barracks after a grueling day of more pointless snow shoveling. The barracks is crowded like a case of sardines, and the smell is unimaginable — stale sweat, clothing mired with excrement, and the stench of human misery. It’s something the boy thought he’d never get past, but somehow he’s become used to it.

A throng of prisoners stands in the narrow space between the bunks, chatting and laughing mirthlessly. They converse in a multitude of languages, the color-coded patches indicating an array of nationalities. “F” inside an inverted red triangle: Französischer — French political prisoner. “T” inside an inverted red triangle: Tscheche — Czechoslovakian political prisoner.

The boy pushes his way around several men, many of whom barely acknowledge him. He looks at each of them furtively, trying to find the person he’s looking for. None of them are him. Once through the thickest part of the crowd, the boy spots a face that looks familiar. That could be him.

The young man sits hunched over on a bottom bunk, blank eyes staring at the ground. As the boy draws closer, he notices the fresh bruises on the young man’s face. That is definitely him.

“There you are,” the boy says.

The young man doesn’t respond — doesn’t even glance up. Maybe — maybe it isn’t him. All the prisoners do tend to look the same with their striped uniforms, shaved heads, and starving bodies. The only things that certainly identify them are their patches and their numbers. The boy hesitates until he glances at the young man’s patch: a red triangle that isn’t inverted. It was something the boy had noticed before, because it’s the same as his own, indicating a deserter from the Wehrmacht.

“It is you, isn't it?” the boy continues. “You’re the one who stood up for me earlier, aren’t you?”

Finally, the young man looks up to acknowledge him.

The boy continues speaking. “I wanted to make sure I thanked you for helping me. It was very brave.”

“Brave…” The young man chuckles as he scratches at lice behind his ear. “Maybe. Stupid … definitely. I guess I just can’t stand bullies.”

“Would it be alright if I sat here with you?” The boy gestures to the bunk. “I have no doubt the spot I’m usually at has already been taken.”

“Sure, I don’t mind.”

The boy takes a seat, trying to find a comfortable position, but it’s nearly impossible on the hard, unforgiving wood. A silence grows between them as the boy glances again at the young man’s patch.

“So … you’re a deserter too?”

The young man blinks, confused by the question, so the boy points to the patch on his own chest.

“Oh, no,” the young man says. “I’m here for a different reason.”

The boy rubs the back of his neck in embarrassment for assuming - especially since deserting from the Wehrmacht is so dishonorable. What could the different reason be, though? He’s afraid to ask, so he doesn’t.

Instead, the boy releases a self-deprecating chuckle. “Well, it figures,” he says. “I guess it wouldn’t make much sense for a coward to stand up for someone the way you did.”

“A coward?” the young man questions. “Is that what you think of yourself for deserting from the Wehrmacht?”

Shamefacedly, the boy recalls the battle. The bullets whizzing past his face. The shells exploding on the pale sands of the beach. His friends fervently laughing over each American they were able to shoot down. Not feeling the same way as they did for some reason …

He pushes it all from his mind, down deep where he thinks it can’t affect him anymore, and he answers the young man’s question the way he thinks he should.

“Of course,” he says. “I was the best sharpshooter in my Hitlerjugend troop. I was supposed to make everyone proud — but all I did when I got to the front lines was run, because I — I am a coward. I let my family, the Führer, and everyone else down.”

The young man regards him with a strange look before speaking. “How old are you?”

“Ah … I turned sixteen in October…”

“So, you’re barely sixteen — still just a boy — and you believe you’re a coward for being terrified on the front lines?” The young man shakes his head. “You feel so guilty for how you reacted, but tell me this: does the Führer not feel guilty for making children fight his wars for him and then punishing them in this awful place for making one mistake?”

The boy is stunned. Such open disdain — how could any German even think such words, let alone say them? “You…” the boy stammers, “you would dare say such things about the Führer?”

The young man smirks slightly. “As I told you already, I’m not here because I deserted from the Wehrmacht.” He looks the boy straight in the eyes, something the boy notices he hasn’t done before this point. “I’m here because I am a traitor.”

“A traitor? To the Reich? As in … intentionally?”

“Of course.”

The boy can hardly even fathom it. Sure, he has always known there were those who opposed the Reich. Scum, degenerates, Communists. The camp is filled with them, but he has never spoken to one before, much less understood why they would even think the way they do.

Then the memory of the beach resurfaces. His friends, all young boys just like him, laughing at killing the Americans — whom he had noticed were also boys when some had gotten close enough to be seen, not much older than him. Why hadn’t he laughed too?

“Why?” the boy demands.

The traitor keeps smirking, like the answer is a simple one. “I hate bullies … remember?”

The boy is at a loss for words.

“What’s your name, kid?” the traitor asks him.

“Fritz.” It sounds strange coming out of his mouth. For so long he has been known only by curse words, insults, or simply as 56836.

The traitor continues to smirk, but now it’s softer. “Well, Fritz,” he says. “You’re younger than me … young enough to not remember a time before the Führer … but I do.”

Comments (0)

See all