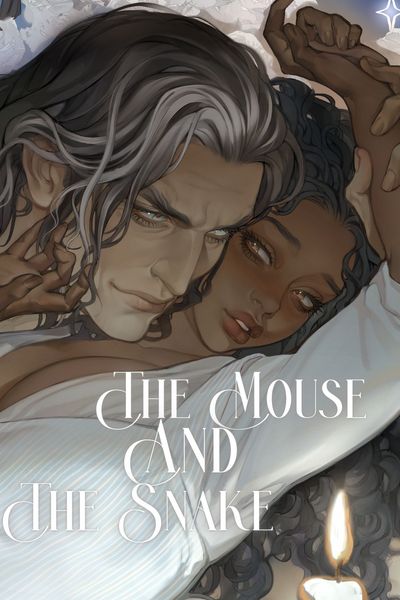

The day had begun with blood.

Not the murderous kind, split veins or crushed skulls. Just the blood of a kitchen girl’s split thumb, chop between a cleaver and an onion that was much too thick to get through. It drifted onto the chopping board as she hissed and wiped her hand on her apron.

Enid didn’t flinch.

For as long as she’s worked in by scraping root vegetables into the pot over the fire, her sleeves rolled up to her elbows, her arms slick with oil and steam. Her hands moved with a thoughtless, rhythmic repetition. Peel, chop, toss. Peel, chop, toss. It was better not to think too hard.

Thinking led to remembering. And remembering leads to fear.

It has been twenty years since she found herself in this world as an orphan. Already poor, already too old to get adopted by one of those charitable, noble families like the way most novel heroines do. At ten years old, she made up her mind to find work and to have a better shelter than the decaying orphanage.

The Ducal estate.

The guards at the front gate had her run off until the senior laundry maid, Maired, a young woman in her twenties at the time, found her eating oats meant for horses in the stables.

“You want to work?” Maired said, perhaps out of pity at the time. “You’ll get shit jobs. No pay, just food and a roof.”

She accepted; she knew the story.

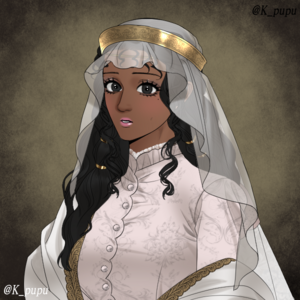

Enid, she was named, for quiet things. As she got older, her role changed was a kitchen extra in a novel she hadn’t even liked. A background character in a story that wasn’t hers. Not even mentioned by name in the text, only referred to as ‘the maid’, and not referred to other than that.

And, she was fine with that.

Because in this world, she had three meals a day, a bed in the servant quarters, and no taxes. No wars. No landlords pounding on her door. No parents to disappoint. Just a job she could do with her eyes closed.

The day she realized she was in another world. She woke up as a child in an orphanage. She wasn’t sure of the year she was born, but she was told she was dropped off as a baby seven years ago to that day.

Her first life wasn’t something to write about either. She worked in accounting, then as a secretary, who was overworked to the point of being quite literally driven to death. She was at her desk, doing an all-nighter with a pot of coffee. She was putting the final touches on the proposal that she had written ten times beforehand when she saw blood dripping on her desk. Then she started to feel uneasy, and after that she passed out. And when she woke up, she was in the body of a child.

As the years dwindled by and she was twelve years old, she realized that she wasn’t the heroine of a childcare novel, and she wasn’t going to be adopted by Duke, so she ran away and applied for a maid job at the Rhadros estate. The only son was 10 years older than her, and she practically watched him grow into a young man and get married over the years.

After a few years of working at the estate, she soon realized that she was in a novel that she hadn’t even liked. One of those childcare ones. The ones where the female lead is found over and the plot conveniently forgets that she has siblings. She wasn’t a side character, a main character, or even a villain. She was a background character, a maid extra.

Unlike some of the upper maids, she was a commoner, which meant that people didn’t pay particular attention to her or anything she did, which was fine by her.

Because as long as she stayed quiet, as long as she stayed invisible, she could live and retire with food in her belly and a bit of money saved up.

“Enid,” said Myra, a younger servant, with red cheeks and a sour mouth. “You’re stirring clockwise; it’s counterclockwise for the morning stew.”

Enid blinked down at the pot. “Oh. Sorry.”

“Honestly,” Myra muttered, “No wonder none of the footmen look at you. You’re always in your own little world.”

Again, that suited her just fine.

Let’s all the pretty girls flirt with the footmen. Let the noble-born maids whisper about marriage and dowries and second chances. In need, just wanted to keep her head down and try to live to 40.

She reached for another potato when she heard a sound.

Tiny. Muffled. But unmistakable.

A child‘s cry.

Her hand froze mid-reach. The world seemed to be still around her.

The stew still bubbled. Myra kept monitoring. Knives chopped. Pans clanged.

But Enid heard it again.

A soft hiccuping sob. Somewhere close.

Something in her heart lurched.

No, because it was unusual; a Noble’s child crying in a house like this? Not possible. But because in this house, the Rhadros estate, a child crying could be a death sentence.

Especially if it’s that child.

Enid sat down on the spoon in her hand.

“Myra,” she said quietly. “Do you hear that?”

“Hear what?”

But Enid was already moving.

She stepped away from the heat, her apron still damp with broth, and ducked out of the kitchen. She knew the layout of the manner like the back of her calloused hand. The servant, quarters when they were here, and lit. An area meant for scurrying, not strolling.

She passed the linen closets, scurried by a storage room, past through a half-open door.

The sound had become louder now.

Tiny. Gasping. Wet.

She pushed the door open.

And there he was.

The Little Lord.

The Prince of the South. Heir to the Rhadros line. Nico Rhadros.

She expected one of the children of the Dutchie, but not the eldest. In the back of her mind, she almost felt a sense of relief, seeing that if it were the little girl, she would have received a death sentence from the Duke.

But seeing the boy, only four years of age, with all the skin and a mop of black hair in the closet was still concerning. He had curled himself on the cold floor of a nursery hallway, his fine coat stained at the sleeves. Silence so shook his small back.

Now that she thought about it, it was the first time she had seen him up close. It was like yesterday. He was just an infant. It was also like yesterday that the Duchess was still living.

He looked even smaller than he did those few times she’d glimpse at him from afar. Tiny wrists. Worn, expensive shoes. A boy born to power, but neglected like an alley cat.

“…Young Master?” she called, no, whispered.

He didn’t answer.

She recalled what she would do to the younger children when she was at the orphanage and crouched slowly, trying to be mindful enough not to startle him. Her knees ached, but she ignored them.

“Are you hurt?” Enid asked gently. “Did you fall?”

Still no answer, just trembling.

And then—

“I—I didn’t mean to—“

His big, silver eyes looked up at her. His little voice cracked, hoarse from crying. “I didn’t mean to make her cry. I just wanted to hold her.”

Enid blinked.

Her?

The baby. His sister. Lady Anisia.

The Duke’s precious, untouchable daughter.

She licked her lip to think for a moment and then smiled.

“Hello, young master. My name is Enid. You don’t do anything wrong.” She reached out instinctively, then he hesitated. Touching the Duke’s air without permission was punishable by flogging. Or worse. But as she looked at the boy’s shoulders that shook harder as a soft sound, she couldn’t just do nothing.

“Enid?”

She nodded, lifting the boy up and then into her arms. In it, those who survived two lives, who have scrubbed blood from the floors and piss from chamber pots, couldn’t bear the sound of a child crying.

“Yes, Enid. There, there, little sweetling.” His large, red-rimmed eyes were filled with loneliness. He didn’t try to push her away or climb up her arms; instead, he burrowed himself into her shoulder and sobbed more. All she could really do was rock him, tell him that he did nothing wrong. Well, thinking about what he said.

Was he punished for making his little sister cry? To the point where he had to hide his tears.

He was such a tiny thing. When she lifted him, it was barely anything. Not like the pills of water she’s carried or the sack of potatoes. But it was as if she were holding a feather.

“How about this? I work in the kitchen sometimes, and although lunch isn’t ready yet, we have some pastries that we finished this morning. I’ll sit you down somewhere warm and you tell me what’s wrong? No one here will scold you.”

Nico blinked. “You… Won’t tell Father?”

“Of course not.”

“You promise?”

“I promise.”

Comments (12)

See all