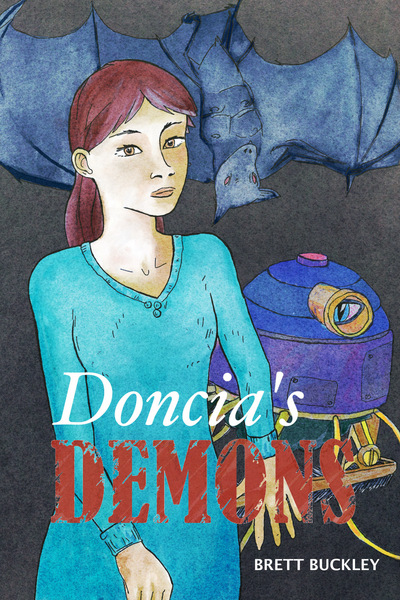

Doncia pushed the mop back and forth across the checkerboard marble floor, which was already quite clean before she started. Isolde had said otherwise; it was a main hallway and must be spotless. Apparently, the robots did a fine job of whisking up the dust, but nobody had designed one that could mop. She wondered what Piri was doing.

A brass spider robot waited patiently for the section of floor to dry before it crossed. Every few minutes it began to click and whirr, waggled its feelers, then seemed to test the floor with one springy leg. It had a turret on top with an eye mounted, looking a little like a short telescope, and she wondered how it knew the floor was wet with such an ineffective-looking eye, and how it knew it was supposed to wait anyway.

She pressed really hard on the ringer and gave the floor a good drying. The next time it tested the floor the robot was satisfied, and it scurried off on its errand.

Goodbye little fellow, Doncia thought after it.

She slopped water onto the next section.

‘Not so wet, girl!’ The voice was right behind and she started in fright. It was an old man with a shock of wavy white hair and piercing blue eyes behind thick gold-framed glasses. White moustaches angled across his upper lips and trailed across his cheeks to his jawline. He wore a long, once-white laboratory coat, stained dark with oil, coal, and what looked like burns.

‘You’re new, aren’t you? What’s your name?’

‘Yes, Sir. Doncia, Sir.’

‘Well, quick Doncia, get it dry. The bots don’t like it wet.’

‘Yes Sir.’ She returned the mop to the ringer, and heard him mumbling to himself as he wandered off down the hall. Among the mumbles she thought she heard her father’s name.

She stared after him, wondering who he was and how he knew who she was, and then heard the three quiet bells Isolde said meant it was lunch time. She quickly dried the last square of floor and towed the mop bucket back to the little room at the end of the hall. She emptied it and hung the mop and set off to find the kitchens. Isolde had said to turn left at every turn except the dragonfly room, and there to cross straight.

Doncia turned left and left, then came upon a circular room with a domed ceiling. Tall in the centre stood what seemed to be a kind of statue. Four large broken wings, each covered with an oily looking membrane, dangled from high up on a splintered timber frame. Translucent hide, torn here and there, was stretched over the frame, and a shaft of light from the skylight at the top of the dome struck it and filled the room with a rich amber glow.

She walked around slowly. Inside the frame were snapped cables, what looked like levers with handles, and even seats. It was some kind of crashed flying machine. It must be a puka ornithopter, captured in the war. It made her sad to see it so broken and forlorn, and horrified that the puka crew had probably died. She wondered why anyone would put it on display.

She was about to continue on straight across from the way she’d come in, but realised, having gone around and around a couple of times, she could no longer tell which entrance she had come in. They all looked identical, with marble frames and arches. She pulled out her pocketwatch and pressed it between her palms, feeling for the echoes of the domed chamber, questing the connecting hallways, but something was making it difficult.

‘What is it you have there?’

Doncia looked up. On a wrought-iron railing above one door leaned a boy a little older than herself. He had dark features and a hawkish nose, and was dressed in a rich-looking blue corduroy suit with a white lace ruffle. He looked down lazily as if he had been quietly observing her for some time.

‘Nothing,’ she said, and thrust the pocketwatch back in her pocket. Poor girls did not own pocketwatches and she was scared he might think she’d stolen it.

‘Please Sir, can you tell me the way to the servant’s dining room?’

‘It’s...’ he raised a hand to point, but the hand dropped. ‘Who are you, anyway?’

‘Doncia,’ she said, and because she was starting to become annoyed with people knowing who she was before she told them, continued with: ‘Doncia Beltran, Professor Javer’s daughter.’

‘Are you really?’ he asked, which was a stupid question. ‘Wait there. I’ll show you.’ He disappeared from the balcony.

The broken ornithopter loomed above, and a movement caught her eye. A blink. Slanted golden eyes watched her from a narrow fox-like face which seemed to hang in the air near the crumpled controls of the flying machine. The eyes stared, and seemed angry. Doncia’s eyes blurred.

I mustn’t believe in this, she thought. She felt a momentary panic, grabbed her pocketwatch again, and forced the apparition to disappear. She shouldn’t wait for the boy; she should get to lunch and talk to Piri. She could still feel the foxy face watching her, even though she could no longer see it. It had to be a puka: the enemy. Was it a ghost of one of the dragonfly’s aircrew?

‘Doncia?’

The boy was staring. She shoved the pocketwatch in her pocket.

‘Isn’t it amazing?’ He gestured at the dragonfly machine. ‘To fly in such a craft.... Wonderful.’

‘It’s sad,’ Doncia said. ‘Broken and sad.’

‘We shot it down at the battle for Braxa Mine. They fought bravely, the puka airmen, but we overcame them.’

‘We?’

‘Not me,’ he said, and smiled but seemed to lose a little of his puff. ‘General Masterson and his men.’

‘Who are you?’ Doncia asked, and then realised she sounded rude—who was she to talk to this obviously important, obviously rich boy? But he didn’t seem angry, or to judge her.

‘I’m Maynard,’ he said, and bowed with a little circular flick of his hand.

‘You are the Marquis!’ Doncia said before she could stop herself. She had met the Marquis of Clee! Should she curtsey or something?

‘I am,’ he said, shaking his head, ‘but I’d prefer if you thought of me as a friend. Anyway, I’m supposed to be at lessons with Rhan Caelis.’

‘You were going to show me the way to the servants’ dining room,' Doncia reminded him. If she didn’t get there soon she might miss Piri.

‘Straight down the green corridor,’ he said, gesturing to one of the doorways.

‘Green?’ All the corridors seemed the same colour.

‘Goodbye Doncia.’

She hurried down the indicated hallway. Though it was mostly creamy yellow she noticed there was a strip of the palest milky green, a paper frieze with little golden leaves, just above where the wall met the marble floor.

She turned left at the end into a narrow, shadowy servants' passage and continued to the dining room.

It was a large unadorned room, and was almost empty, but Piri was in the centre of one of the long tables near Moni and some other chatting maids. Her plate was already empty.

‘You missed your mum,’ Piri said, ‘and Isolde was looking for you.’

‘Sorry,’ Doncia said, ‘but I was talking to the Marquis!’

‘Were you? What’s he like?’

Doncia thought about that. ‘Actually, he was nice. He helped me find my way when I was lost. He was wearing a silly corduroy suit.’

Piri laughed. ‘Ask me what I’ve been doing.’

‘Tell me.’

‘I’ve been working with Moni. She’s important—she has Countess Sabra’s suite!’ Piri lowered her voice to whisper: ‘It’s strange.’ Then in her normal voice she said: ‘But you need to get some lunch.’

Piri showed Doncia through to the kitchen. Lunch was little filled pastries, and Doncia piled a few on her plate. Piri tried to take a few more, but the mean-faced old cook shooed them back out to the dining room. They sat at the nearest table and Doncia took a bite of the first pastry. Spicy meat oozed into her mouth.

‘Not bad, hey?’

‘Yummy,’ Doncia said, and chanced a look around to check that Moni and her friends weren’t listening. She whispered: ‘What’s strange about the Countess’s rooms?’

‘There is so much stuff—it’s weird and beautiful. It’s like being on a ship, with rigging and treasure and everything.’ Piri leaned closer to Doncia’s ear. ‘You know what they say?’

‘What?’

‘That she was once a pirate captain but the graf captured her ship—and forced her to marry him!’

‘No!’

‘That’s what they say.’

‘They-who?’

‘Moni.’

Doncia looked at Piri in disbelief.

‘Why would she lie?’ Piri whispered.

Isolde came in looking tired and exasperated.

‘Doncia!’

Doncia swallowed a lump of pastry. ‘Yes—Isolde?’

‘Where’ve you been? I’ve been all over. The mopping should have been quick.’

‘I got a little lost. At the dragonfly room, but the marquis was there, and he showed me which way.’

Isolde leaned across the table.

‘A little warning, pet. It’s best not to get too chummy with the marquis; we think he spies on us.’

‘Spies for who?’ Doncia asked.

Isolde shook her head. ‘Just stay away from him, and out of trouble.’

‘Yes, Isolde,’ Doncia said, but it just made the marquis all the more interesting.

‘Back to work,’ Isolde said loudly, and stood. She glared at Moni and the others, ‘All of you.’

Doncia stuffed the last pastry in her mouth and waved to Piri, then followed Isolde.

🔸⏱️🔸

Doncia’s mum walked them home, out under the arch and down the cobbled street between the mansions. Captain Anton called out a cheerful farewell and Doncia waved.

The streets were quiet, with only themselves and other weary workers hurrying home, heads down and purposeful.

‘How was it?’ Mother asked. She was a silhouette in the last rays of the sun between buildings, a bulky shape with her clothes rack and ironing sack.

‘I’m sore,’ said Doncia. ‘I spent the afternoon up and down ladders dusting cobwebs. My neck hurts, and my back.’

‘I was scrubbing the floor in Countess Sabra’s bath chamber,’ Piri said. ‘My knees are red and burning, and there’s hardly any skin left on my fingers.’

Mother laughed. ‘It’ll hurt more tomorrow. Bit different from school?’

‘Will the graf reopen it?’ Doncia asked, and sighed, knowing the answer already.

‘You’ll get paid you know. Then we can afford to buy some books for you to study at home. I’d ask Mr Langwish to recommend some, but....’

‘Poor Mr Langwish,’ said Piri. A dark shadow seemed to pass over Piri’s face then, and Doncia instinctively looked up. She caught the briefest glimpse of a shape disappear over the roof, heading back toward the castle. It was the demon she’d seen the other night!

‘What was that?’ Piri asked.

‘A demon!’ Doncia whispered.

Mother was looking up too, in the direction the shape had gone.

‘That was strange,’ she said, and shook her head.

They hurried now in silence, like the other workers with bent heads, and saw Piri to the foyer of her tenement. Mother gave her a parcel.

‘Your uniform.’

‘Thank you, Mrs Beltran.’

At their own foyer Mother fumbled with her keys, and dropped them onto the steps. Doncia scooped them up and unlocked the door.

Mother latched the door quickly, and sagged against it for a moment.

‘Mum?’

‘I’ve seen that thing before, once,’ Mother said, straightening up. She bit into her lip with her front teeth. ‘Just before your father....’

‘Before he was touched?’ Doncia whispered.

Mother nodded.

Doncia shivered. She’d better not tell Mother about the other night, on the roof.

She looked through the glass of the door, back into the street. Just a wash of mauve remained in the one visible patch of sky. Across the street was a small cloaked figure. Doncia thought she knew who it was: the beautiful boy.

‘Come on.’

She grabbed her mother’s arm and hurried her toward the staircase.

Comments (0)

See all