“The meteors are late,” I complain, checking my watch. “Didn’t the news say 10:30?”

“Maybe they meant Idaho time,” Maja says, still lying beside me on the blanket with her eyes closed.

I grumble at the thought, then perk up a little. “Hey, what time is it in Montana when the sheep get caught in the fence?” I ask her in English, to which she responds without missing a beat:

“Mountain time!”

“Ah, Montana, where the men are men and the sheep are scared,” I say, and I chuckle, though as a large animal veterinarian who often makes calls to crass cowhands, I’ve both heard and told the jokes a hundred times already. But Maja does not respond.

“Draga?” I prompt her softly.

“Mh?”

“It’s too much for you, isn’t it? We should head back inside after all…”

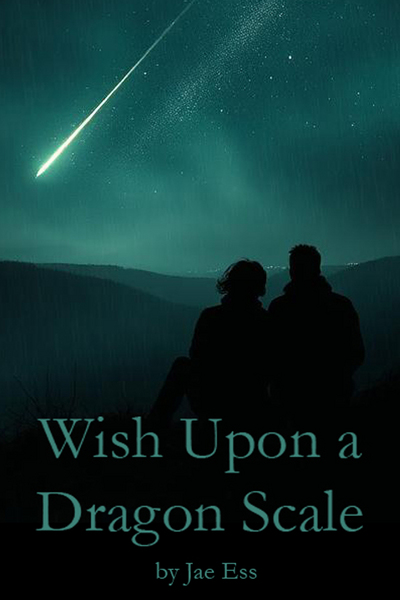

“I’m fine. I wouldn’t miss this for the world. So many space dragon scales falling all at once… There’s nothing more beautiful…”

I frown and I feel a crease form between my brows. I can’t help fretting over her.

“Are you sure you’re comfortable? You’re not too cold? Do you want me to get you a better pillow?”

When she does not answer right away, I become anxious.

“Draga?”

“I’m fine,” she says, her voice faint but contented. I realize her hat is crooked. I reach down to straighten it, and it slips easily over her smooth scalp. Maja opens one eye and smiles at me tenderly, and my gut clenches at the sight.

Even now, she is so beautiful.

Just like she was then…

***

Yugoslavia

1999

It took a few weeks for us to finally get the news my mother was killed in a car accident. A car full of protesters on their way to a certain bridge, they were hit by an oncoming truck. Everyone in the front seat was killed instantly. At the time, I remember it was little consolation to me that, thanks to the other protesters, the bridge she had gone to save was spared.

Just like that, I found myself an orphan.

I’d never known my father, and Mama’s parents were dead. I thought she might have had a sister in Hungary, but I did not know her name.

The next day, while I cried myself into a fever, Stanko and Baba went to the police to see what ought to be done about me. There were many displaced children in the conflict, and the government had enough on its plate without adding another homeless waif to the mix. When Baba offered to solve the issue and take me in while the paperwork was being processed, they made no protests.

That June, after eleven weeks of NATO airstrikes, the conflict ended when President Milošević officially withdrew our forces from Kosovo, though people on the news said life in our fractured country would never be the same. For me, that felt especially true.

With the bombings ended, Baba and I left Branislava’s house and went to live at her apartment near the high school, in the same city as Maja and her family.

I learned Baba was a retired school custodian. Her eyes were failing, and there had even been talk that her move into Branislava’s house during the air raids would be permanent, but now that I had come into the picture, the old woman was more than pleased to return to her own home and rely on me for those little tasks she could no longer do independently. I, for one, didn’t blame her for wanting to get away. Living in that house with six other children and three adults, while not all unpleasant, had been noisy and chaotic, and Baba and I were both the type who valued our peace and quiet. But living alone had it’s drawbacks, too.

Baba lived on a meager pension, and that meant we were poor, almost poorer than poor, though we did have the apartment—one room—with a shared toilet and shower on the ground floor. Baba slept on the couch beneath several layers of colorful crocheted blankets; I slept on a cot on the opposite wall. Between us was a green plastic table on which we prepared and cooked all our meals with a single burner propane stove, and two plastic chairs. We had no refrigerator, no appliances of any kind, but we did have cold water on tap, for which I was grateful.

So it happened I was beyond astounded to receive my first present from her: a rusted, thirty year old bicycle. I don’t know how she got it or what she paid for the thing, she might have pulled it out of the garbage dump for all I knew, but she may as well have given this child wings for all the joy and freedom it afforded me.

That summer I rode my bike to Branislava’s house almost every day, and from there, with the older children and no chaperone, to the park or the city center, or the river just outside the city. There we’d swim and play for hours, gorging ourselves on the wild raspberries that grew on the bank till the sky turned pink with sunset, and we were left scurrying to get home by dark. These were strange, sweltering, brightly colored months, raw and poignant, where I felt at any given moment as apt to laugh and whoop for joy as I did to break down and scream for sorrow at the loss of my beloved mother. But through it all, I had my new siblings, Maja, Dragan and the others. And, I had Baba.

In character, she was solid as a rock, constant and enduring, but not hard. She was gentle always, and sweet, a never-ending fountain of love and patience. There was nothing I could say or do that would ever anger her or push her away, though in the beginning especially, I tried to do just that. But she remained undaunted, and her arms became my refuge, my one true safe place.

In September I learned somehow Baba had managed to get my records transfered over from my school in Belgrade, so I was able to attend classes. Maja especially was excited, and told me we’d be in the same grade.

“But you’re a year younger than me.”

“Not quite. Your birthday’s in January, mine’s December 25th. I make the cutoff for grade 4 by six days.”

“December 25th. Isn’t that—”

“Catholic Christmas,” she said smugly.

“No one cares about Catholic Christmas. My birthday is January 7th.”

Her eyes got wide. “Christmas.”

“Yeah,” I said with a grin. “We’re both born on Christmas.”

Maja and I ended up in the same class with Mr. Skakić, a small, mild man with a reedy voice. He never struggled to compete with his students for volume, and always spoke very quietly. In fact, almost counterintuitively, the quieter he spoke, the closer we listened.

Very smart and professional, Mr. Skakić was practically the perfect teacher, though he made one mistake. He sat Maja and me next to each other—in the back row.

It was inevitable that we should get into mischief. The pair of us were thick as thieves going into it, and devoted far more attention and creativity to the silent games we played with each other in class than we ever did to our studies. Fortunately, we were both quite smart, so our grades hardly suffered for all our goofing off.

One day while Mr. Skakić was busy at the blackboard teaching us how to divide fractions, Maja passed me a notebook. She indicated I should open it. On the first page she had drawn one of her space dragons; beneath it, she’d written a poem.

Pavle lebdi tiho u svemiru

Pred njim se planeta sija

Uživa u njenom miru

Život je večna fantazija

Pavle quietly floats in space

A planet shines in front of him

He’s enjoying its peace

Life is an eternal mystery

Her pencil sketch of the serpentine dragon looking at the beautiful planet was very good, but well, boring. Like the poem. To my mind, it was definitely missing something.

Action, I decided. What this picture needed was an explosion! Grinning to myself, I brutally vandalized her sketch with my own drawing and caption.

Then Monet flew in and punched the peaceful planet and it exploded—BOOM! I scribbled starbursts over the planet to indicate its destruction. Then with my limited skill I drew a fighter that resembled Goku beside Pavle the dragon. In a speech bubble above his spiky hair, I wrote in all capital letters just like in a comic book, “You’re next unless you give me a dragon scale!”

I waited until the teacher had his back turned once more, then I passed the notebook back to her. She opened it and immediately snorted at the picture.

Mr. Skakić looked back sharply. A quick thinker, Maja raised her hand and asked to blow her nose. He let her get a tissue. She returned to her seat, face red with suppressed laughter, and immediately began drawing in her book. A few minutes later, she passed it back to me. Bursting with anticipation, I opened it to find a second panel to our comic, showing Pavle chomping Monet’s head off, a perfectly succinct punchline. The way she drew the character, surprise and dismay could be seen in every limb of his headless body, a masterpiece on lined paper.

Inspired, beneath it, I drew the next scene with far less skill, but no less effort and imagination. Pavle the space dragon, looking a little sick. And in the scene below that—giggle!—he pooped out the head. Spiky haired Monet grinned triumphantly and said in a speech bubble, “You can’t defeat me that easily!”

I watched Mr. Skakić once more, waited for just the right moment, and—pass! Maja opened the book and went positively scarlet. She bent forward on her desk with her face towards me and I could see tears in her eyes as she struggled to keep her laughter in.

It was contagious.

Perhaps to others it wouldn’t be all that funny, but somehow, to us just at that moment, it was the funniest thing in the world. For the next fifteen minutes every time our eyes met we had to put our heads down and cover our mouths to keep from breaking out with laughter. It got so bad that Mr. Skakić finally caught on, to Maja at least, and asked if she needed to see the nurse. In a shaky voice she replied no, and that she’d feel much better if she could go to the bathroom. He excused her, and I envied her quick thinking when I imagined her screaming with unrestrained laughter in the girls room at the end of the hall.

Later when school got out we were still laughing about our comic, and as she walked me to Baba’s, she asked me, “But why Monet? That’s the worst!”

“He’s an artist! Like one of the ninja turtles. Anyway, Monet’s a better name than Pavle,” I said, holding my sides. “That’s the worst dragon name I’ve ever heard.”

“It’s perfect,” she said, wiping the tears from her eyes. “The adventures of Pavle and Monet. Rivals in space!”

Comments (1)

See all