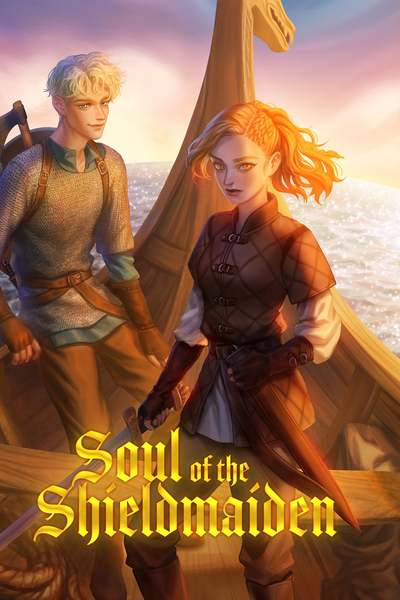

My first truly vivid memory is the longship cutting its way through the dark waves and sliding its slow way up onto the sandy beach.

I’d snuck out of the house to watch the waves, as I often did. Papa would always be angry with me, he said it was dangerous for a girl of eight summers. He said I’d be sucked out to sea. I didn’t care. I’d slip out of our cottage at night and come down to the shore to stare at the sea and let the water sing me its crashing song.

When I did, I let my long, scraggly reddish-blonde hair blow behind me in the ocean breeze. My dress flapped about my skinny, often bruised legs. But my light-brown eyes would simply stare out at the ocean, constantly singing, constantly dancing.

Which is why I stood motionless as I looked at the ship atop the moonlight-crested waves.

I didn’t know to fear the dragonhead carving which sat atop the ship’s bow as it came to greet me. I found the long, curved lines of the planks overlapping each other to be pretty, not intimidating. And as it approached, I could hear the drumbeat and watch the oars dance to it in their little motion.

I didn’t know what it meant for my village. Didn’t know the town of Strongricstead faced any sort of danger from that lean, lithe ship sliding its way up on the shore.

The men who leapt from it, however, left little to the imagination.

All grown-ups looked tall to me. But these men stood a hand or two taller than anyone I’d ever seen. They all wore mail, and carried shields. As they began to leap from their beached ship, one of them gestured to me and said…something. I didn’t understand the language at all. But the first one down from the ship pointed at me, said something, and all the rest began to laugh.

That I understood. So, I did the only sensible thing and kicked him in the shins.

That brought another round of hilarity from the men. The one I’d kicked smiled at me, then nodded, as though he approved. He turned to the last man to disembark, an older, grey-bearded warrior with a nasty scar across his cheek. They spoke for a bit, then the older one grabbed me and scooped me up and tossed me into the ship.

I didn’t land smoothly, and caught a small splinter in my hand. My yelp of pain drew another round of jocularity, and most of the big men unslung their shields from the back and began walking up the shore towards the village. The older one, and one other, stayed with the ship, looking up and down the beach warily.

That’s when the screaming started.

I can’t give you a description of what happened to my village. I wish I could tell you I watched. That I leapt from the ship and made a dash for it, for my parents, my brother. But I didn’t. I ducked down below the gunwales and hid, as though the monsters hadn’t already found me.

I didn’t hear the clash of battle; nobody in Strongricstead even owned a sword. Sometimes, I wonder if my father tried to fight with a pitchfork or a hoe, something. I wonder whether my brother stood before my mother. I wonder a lot of things, even now—but I’ll never know, not for sure. All I can tell you is I heard a chorus of screaming joining laughter and shouting from my captors.

As the screams died down, men began flinging large, filled sacks into the ship with me. They landed on the wood with a loud clank.

Curiously, I opened one of them. As I peered inside, I saw the golden cross from the church, the one bit of gold in the village. I saw the silver candlesticks and goblets, from the church as well. I saw bits of jewelry, some cheap, some not, collected from the women of the town. I saw a spice-box from the merchant, rich with the smell of cloves and pepper from some foreign place.

And then others. Gilda, the girl from two doors down, they wrestled into the boat. She fought even as they hoisted her over the gunwale and into my view. Her dress had been lowered down, exposing her breast, but she fought and kicked and screamed, to no avail.

I found myself idly considering her screams. The horror of the night simply didn’t hit me. I remember being scared, but I don’t remember feeling much else. Sorrow, panic, grief, rage…none of those. My mind simply slipped away from the reality of the situation. And so I pondered why Gilda screamed. It seemed to gain her nothing. If anything, I thought as one of the Norsemen hit her in the face to silence her, it seemed pretty counterproductive.

Looking back, I know the things I should have felt. At the time, my mind wouldn’t let me feel them. Instead, I simply felt numb, as though all of this was happening to someone else. And that allowed me to stay calm, which in turn meant I wasn’t getting punched like Gilda.

Next came Ecgmund, the miller’s boy, a long, lanky boy who had a habit of teasing me for my always-dirty skirts. He’d been bound hand and foot, and gagged. Then Aethelhun, the smith’s apprentice, large, strong, and likewise bound. And…nobody else. Had the others survived?

The Vikings began vaulting back into the ship, taking their place at the oars. Some of them had blood on their mail—and none of them looked wounded. So not all the others had survived, then.

I couldn’t understand their words, but the tone of their voices carried the same bravado as Old Brithnoth when he told his fishing stories around the tavern fire. Lying to each other about their deeds in Strongricstead, I guessed. Every once in a while, someone would gesture towards us four captives as though to make a point.

All the while, the ship cut through the sea. I found I quite enjoyed the motion, the rhythmic rise and fall of the deck under me. I treated it like a game, moving my body to adjust with the ship, and I tried really hard not to cry. Crying is not a thing big girls do. I knew that much.

“Aelfwyn?” asked Gilda in a whisper. “Did they…are you still whole?”

I nodded to her, frowning. “Of course, silly,” I said. “I’m not even promised yet.”

“These men…” she said, then choked back a sob. “They—”

“Vaer stille!” The old man who’d flung me into the boat shouted at us before I could learn what Gilda wanted to tell me. We both looked up at him, trying to figure out what he wanted. “Stop med at snakke,” he added, slowly, as though the speed at which he spoke his foreign tongue would mean anything to us. I just kept staring at him, and he sighed. Then he took his hand and pointed to us, then pinched his lips between his finger and thumb.

Oh.

I nodded to him, then closed my eyes and let the ocean lead me in her little dance. She rocked me as though she were my mother—the closest thing I had left to me in the world.

And she carried me towards my destiny…and towards Erik.

Comments (0)

See all