The next day Byron’s fortunes were suddenly transformed.

He’d written to a friend of his mother’s and explained his predicament. He couldn’t bear to tell his mother. This friend, who was a younger woman and a neighbor, organized an “exeat,” or pass, from school for the day so she could take Byron to London. The headmaster had decided to give Byron one more chance. He would not be expelled—for now.

“But, how’d you do it?” he asked her as they bowled down the hill in a smart navy-blue barouche that had leather seats and basket-weave panels on its sides. Several boys had seen him in the carriage and given him admiring looks.

“I simply told Dr. Drury that inheriting your estates at age ten had not been easy. Nor losing your father at two.”

“I’m not the only one,” pointed out Byron. “There are any number of boys like that at school.” He was thinking of Clare and De La Warr, who’d both inherited estates as boys. The memory of what had happened with them still ached. He was afraid the loss of their friendship was permanent. It still made him feel sick.

“And that your nursemaid had to be given the sack,” added his companion in the carriage.

Byron was so embarrassed that he couldn’t reply to that. His nursemaid wasn’t someone that he usually thought about. In fact, he’d tried so hard and so successfully not to think about her, that being reminded of her now shocked him.

May Gray. That was her name. She’d looked after him when he was very little. He’d been attached to her. She’d been more tender and affectionate with him than his own mother had. She dressed him and undressed him. She admired him in the mirror. She kissed him and combed his hair. But then she’d taken to climbing into his bed at night when she came home from the pub. At first, he liked this. He liked the warmth of an adult who wanted to sleep with him. He was sure she loved him. But she’d begun to touch him. He wasn’t sure, but he sensed this wasn’t right. He couldn’t have put this into words if forced to. It was shame and pleasure and confusion all mixed together in his mind.

He’d told no one about it until he inherited his barony. Then, tentatively, uncertainly, when he was assured by the solicitor that he had the power to decide, he’d told the man what he wanted. That was to have May fired.

It was his first adult decision and he still felt that age ten was too young to have been forced to make it. He still wasn’t sure the whole thing hadn’t been his fault.

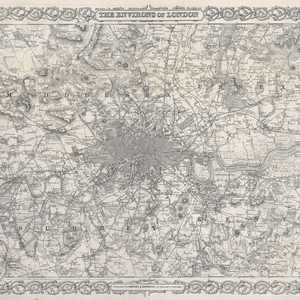

These gloomy thoughts prevented him from seeing what was around him. His companion in the carriage made a series of exclamations. She saw he was disturbed and tried to distract him. She kept up a running commentary on what they were seeing as they approached the great metropolis. “This is Bayswater!” “This is the park!” “This is Oxford Street—lovely shopping.” “And this is Charing Cross Road, all the booksellers are here!”

Byron now shook his head and looked around. Harrow was a sleepy place with nothing happening, but he now noticed theirs was not the only smart carriage in the road. There were a dozen of them. There were riders on horseback and servants in livery. There were men wearing black top hats. There were women wearing full skirts with a glossy sheen. There were shops with books in the windows. This was sophistication. This was fashion. This was town.

His heart beat faster. In that moment, he had his first glimpse of a magical place. For London was not only a soothing antidote to what had happened to him at Harrow, it was his future.

Comments (2)

See all