Sam snatched an apple from the bowl next to the door before swinging out onto the street.

The garden was overgrown and treacherous, despite Sam's best attempts to tame it, and it had more thorns crawling out of it than a fairy tale.

He was used to manoeuvring them without snagging his clothes on them. Albert, the old, white goat that wandered in for a crust of cheese every now and then, reared his horns to butt Sam in the leg as he walked by. He still couldn't figure out if it was meant to be affectionate or if the creature hated him.

Sam enjoyed walks in the morning, mainly because Coursi did not get up till noon and he had the small hut to himself. As soon as Coursi was awake then he started practising alchemy, which usually meant trouble. It had been five years since he had moved from his home into Coursi’s, and he supposed he had learnt a lot. Mostly that alchemy was very difficult; he supposed this was the reason Coursi always had so little success.

He remembered he had been terrified that first day. There had been an awful feeling in his stomach and he didn’t want to face anyone from the orphanage. He had spent years declaring that his mother would never find work for him, because he was her son. But he had been wrong. She had ferried him off to the mad old ‘wizard’ over the road. He had come from somewhere in the east, bringing with him the trade of alchemy. Everyone in the town called it fae’s magic and shunned him. They believed he had been learning from them, conspiring with the enemy. This, Sam found, was nonsense. Alchemy was magic, but it was an entirely different sort of magic. It ran from rules and inner strength and a gift from what Coursi referred to as ‘the celestials.’ He had told Sam these were deities, and when Sam had asked what that meant, nature spirits. They sounded a lot like faes, but Sam had been assured they weren’t.

“Fae’s are tricksters,” Coursi had explained. “Celestials are benevolent.”

The man had seemed strange, with his long, dark hair and dark skin and strange accent. He had seemed very big and loud when Sam was ten, but he had discovered Coursi was just a little awkward. Especially around a ten year old who, as Coursi had mentioned to his mother, was showing signs of having alchemical talent. Sam had a theory he only pretended to be mad to avoid speaking to other people.

He was also completely incompetent when it came to anything domestic, which was why Sam was heading into the marketplace now. The place was a bustling beehive of activity and the main buzz of gossip for months had been the Queen’s newest daughter, but with the Prince’s birthday fast approaching, the topic had turned to what his coming of age quest would be.

Sam wasn’t interested, and it most definitely wasn’t because the people his age veered away from him in the marketplace. He decidedly did not care what they thought of Coursi. He liked being alone.

He supposed, plucking at a rabbit at the butcher’s stall. It didn’t seem to believe him either, so he brought duck for dinner instead. Ten minutes later, and he was equipped with a loaf of bread, a wheel of cheese and a small garden of vegetables.

The last thing on his list was, of course, apples. Coursi didn’t eat them, which was just a well because when the market had the shiny, red ones, Sam hoarded them like he was a dragon and it was his treasure. He stared at them as he waited to be served. They gleamed like gemstones in the morning light and he was almost salivating, having finished his own around ten minutes ago.

“My best customer!” the vendor, a pretty woman with dark hair and a wart on her jaw, smiled when she spotted Sam amidst the crowd. “The usual?”

“A baker’s dozen,” Sam said, adding “please,” as an afterthought.

“Making up for all the money you cost me in your youth then,” she bellowed, but she always bellowed to some extent.

Sam only smiled at her sheepishly. He had gotten quite adept at swiping from her stalls when he had been living with his mother. A whole group of them had done it – they had even taught Scoundrel the ancient wolfhound to help.

“Saw a few of your old pals here the other day, on an errand for some posie or another,” the vendor continued, and Sam shuffled his feet. She was putting the apples in the bag as slowly as possible. She evidently wanted to chat this morning.

“Yeah,” he said, noncommittally. That was their job, he wanted to add. They all had jobs now – his mother had made sure that every orphan had found some occupation.

“You must be lonely – especially without that girl you used to go around with – what was her name?”

“Beatrice,” Sam was getting impatient now.

“Beatrice. You know, I always fancied the two of you as sweethearts? Bet if you met now it would be like something out of a fairy tale.”

“It wasn’t like that,” he had told her this before. Several times. He knew what her next question would be-

“Have you found a nice girl yet, Sam?”

He shook his head dismissively and held out his hands to take the bag of apples. He was getting fed up of being asked about girls. Chasing girls seemed to be the main reason boys has age came to town – girls were the ones doing the shopping and pretending not to notice them. They were pretty, he supposed, but he couldn’t see himself kissing any of them, let alone marrying one.

“Better start soon. You don’t want to end up like Coursi, do you?”

Sam gave a half smile that dropped into a frown when he turned away. And what was wrong with Coursi, he asked himself. He was a successful alchemist. He didn’t live alone, he had Sam, and they were happy together. If he had a wife, things would be odd. It would be like a three legged goat – there would be something off-balance. Sam couldn’t imagine the man with anyone romantically. The idea was laughable.

He hadn’t always cared that much. He had used to be scared of Coursi – all of the children had been. When his mother had walked him across the road to work there, he had wanted to cry and scream. He would have cried and screamed if she hadn’t of ran her fingers through his hair and murmured, “I really need this to work out, Samuel.”

So he had been brave.

And it hadn’t been that bad, in the end. Not now that he knew how to get out of the way.

The bags in his arms veered forwards suddenly and he cried out as the apples began to slide away from him in a crimson avalanche.

Hands caught them before the hit the ground, and Sam found himself staring up at a boy in knight’s armour.

“Got your hands a little full there, huh?” the boy said.

He was smiling and it seemed to light up his whole face, making him appear like a Greek hero. His skin was dark, as dark as Coursi’s, and his face was framed with dark curls, like someone had rustled a pile of autumn leaves. His nose was long and straight, and his jaw was strong. He was handsome and Sam couldn’t decide if the scar trailing from his cheekbone to the corner of his chin made him more so.

The knight had spoken to him. Sam had barely heard the words, but he knew he had to stop staring and respond.

“Uh, thanks,” he squeaked out. His throat had suddenly dried up. He had no clue why.

The knight’s eyes – so dark they were almost black, sparkled, and he opened his mouth to say something, when a sharp voice cut across them.

“Elexander – I need you over here!”

“Duty calls,” the knight said, with a roll of his eyes to Sam. He balanced the apples carefully on top of Sam’s loaded arms. “Be careful, yeah?”

Sam clamped his mouth shut and nodded, not trusting his voice again.

“That’s my boy,” the knight gave him another twinkling smile, before he disappeared through the crowd.

Sam stood for a moment, unsure of what had just happened.

His shoulder was jostled and he started on the path home again, fearful to drop anything – as though the knight would be disappointed if he did.

He had never seen him before. Knights lived near castles, and there were no castles in Pondcombe. He must have been visiting with his lord.

And yet he had smiled at Sam. He had called Sam his ‘boy’.

Why did it make his cheeks tingle and his chest feel so inflated?

It was the only thing he could focus on as he stepped around a sleeping Albert and shouldered the front door open.

There was a loud pop as he entered.

“I needed you five minutes ago,” Coursi snapped from the table. He spoke quickly and firmly, so he sounded like he was snapping.

“We were out of food,” Sam said, finally finding his voice. This was normality, and he could cope with normality.

“So, you picked up the essentials,” he gave a pointed look at the apples in Sam’s arms. “Well, hurry up and get over here.”

Sam ducked into the larder, a side room to the right of the front door and left the groceries in a heap in the corner, before approaching Coursi’s desk.

One room dominated the downstairs, with a fireplace built into the left wall. A pot was strung over it, usually full of leftovers that Sam could snack on throughout the day. It was choked with ashes, and sometimes spat them at the two spindly chairs that had been pulled up alongside it. Sam’s mother had equipped them both with cushions that had long since worn thin. A few cupboards were pressed against the wall, but their contents over flowed onto the tops of them and the floor instead.

Coursi’s huge, oak-wood desk sat in the middle of it all. Almost all of the legs had been hacked, chewed (curtesy of Albert) or singed, but it determinedly held fast. On it was a mess of vials, paper and leather pouches, spilling herbs and powders unceremoniously over everything. Every inch of the desk had been marked in some way.

In the middle of it sat an alchemy board, a slab of wood with two sliding rings, one with the astrological symbols and one with planetary symbols.

“I’ve been trying this formula all day. Can’t seem to get it right.”

Sam glanced at the table. Only a small pile of ashes remained and were quickly swept to join the other failed attempts. It looked as though the mountain had spontaneously grown a miniature grey mountain. There was a pile of plucked daisies on one side of the table.

“And you’re attempting what?” Sam asked.

“To turn organic matter inorganic,” Coursi said, as though it should have been obvious. “Flower to metal.”

“Why?”

“Iron is the most effective weapon against faes. Iron is mined. Mines are an exhaustive supply, not to mention the time it takes to get it up here. Plants are less exhaustive, if correctly cultivated,” Coursi spoke quickly. “I’m sure it comes under Aires. The heat helps the process like a smithy.”

The astrological symbols helped channel the power of each celestial, if you were touched with the gift of alchemy. Sam had heard a rumour that you were gifted with alchemy if you were the descendent of a celestial, but that sounded like nonsense.

“If you want iron, why are you using Saturn?” Sam pointed to the outer ring of the Alchemy board. The planets channelled metals that enabled the transformation to occur. But Saturn was for lead. “Shouldn’t you use Mars, for iron?”

“Plants are made the same as lead. Just organic,” Coursi said.

That didn’t seem right to Sam, but he didn’t know enough about either to dispute it.

“Have you tried Mars?”

“Fine. I’ll combine Mars and Aires,” Coursi said. Sam couldn’t figure out why he was emphasising them. It sounded like a test, but he was certain he was right.

He watched as Coursi placed another daisy onto the alchemy board, taking a breath to focus himself. He had told Sam that inner piece was the most crucial part. Only then could you tap into the celestial’s power.

The alchemist spun the board into place, then struck a match and pressed it to the daisy. It instantly struck up in flames. Coursi frantically wrote in the air with his hand, the symbol for Aires, but the fire only spread. It rapidly engulfed the table, ravenously chewing up the wood.

Coursi’s amber eyes met Sam’s over the flames.

“Fetch some water then.”

There wasn’t time to snap a sarcastic retort. Within minutes, the whole hut would be on fire, so he dutifully ran to the backdoor. Nettles and thorns grasped at him as he headed to the well at the bottom. The bucket had already been left down, which Sam thought proved that being lazy had its merits.

The water sloshed onto the muddy path as he pushed through the undergrowth back to Coursi’s misshapen hut, throwing the water blindly as he barged back through the door.

There was an angry hiss as the flames died, leaving only the thick black smoke to drift out the window.

“Look at that, Leffy, the dragon’s been slain,” it was a voice Sam recognised and made his stomach jolt.

“We have visitors,” Coursi commented to Sam, needlessly.

Two boys were standing in the main room of Coursi’s house. One was the knight from earlier, wearing the same smirk as when he saved Sam’s purchase. The other was decidedly more soaked from Sam’s water pail and looked considerably more irritated, his blue eyes seemed to be brewing up a storm. Sam felt he could sense the boy’s anger like heat from an open fireplace. His fair hair, worn just shorter than Sam’s unruly nest, dripped water down his pale face and onto the fine livery he was wearing. That was the scariest thing to Sam. He’d never seen clothes made of silk before, yet here it was before him. An azure silk tunic and matching breeches, embroidered with gold in swirling patterns of thistles and thorns. He looked like a Lord, at least.

And Sam had just thrown water him.

“Shall I put the kettle on?” he squeaked, hiding the bucket behind his back as though he could erase the event.

Coursi nodded, not looking at Sam as he offered the two visitors the chairs by the fire. The blonde boy raised an eyebrow at them, but took the one with all its legs. The knight from before made his way to the other one, before he paused and looked back at Sam.

Sam frantically looked anywhere but him, wondering why Coursi was acting so calm. It was as if he knew this pair.

“Hang on,” the knight said. “Leffy-“

“I told you not to call me that in town.”

“-He could be your twin,” the knight said. “Don’t you think?”

The Prince frowned at his knight, looking baffled, then he turned towards Sam, as though just remembering his existence. His eyes pierced into the apprentice’s face, and Sam could only blink back and wish he was somewhere else.

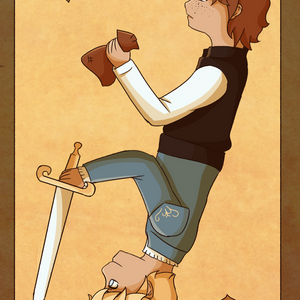

“You see it too, right?” the knight turned to Sam with eager eyes, but Sam could only shrug. He couldn’t remember the last time he’d examined his reflection but for passing windows and streams. Sam glanced back at the Prince. Did his nose really stick up like that? Was his mouth really so feminine and bow shaped? The eyes he could believe, they were similar to his mother’s, slightly downturned and the same colour. The one difference was their hair. Sam’s decided to stick up in odd places and was auburn, almost red when the sun hit it.

“The similarity is remarkable,” Coursi murmured. As though they had planned it, both the Prince and Sam turned to see him rubbing a hand over his goatee, his eyes flicking between the two of them. “Imagine an alchemist’s apprentice who looks just like the Prince.”

Comments (4)

See all