Spectro war born in 1914. Though born during the Great War in the Air, he was fortunate that his earliest memories were of a time of fresh peace. Horrified by the bloodshed of the Great War, the industrialized powers looked to exploration and science as ways to gain dominance over marital aggression. The fathers of the current generation were soldiers, but vowed that their sons would be scientists and explorers.

Spectro had good memories of his boyhood. For an inquisitive boy such as he was, the early 20th century was a fascinating time. Dr. Wilbur Link, the world’s leading roboticist, developed “Link dolls” to educate boys on the mechanical actions of robots. Spectro kept a collection as a boy and to this day keeps them tucked away in a corner of his house broken parts and all. Jason Gridley’s discovery of the Gridley wave allowed communication across the astral realm bypassing the limitations of physical distance. Every night, America could tune into the Jason Gridley Hour and listen to reports on faraway lands like chivalrous Barsoom and savage Pellucidar. And every night, Spectro listened wrapped in a blanket next to his family’s radio in the kitchen. Words crackling on electric static sparked his imagination into fiery daydreams of jeweled cities and dark jungles.

In the present, Spectro listens to recordings of the Jason Gridley Hour. He no longer finds them adventurous in the face of what he sees in his daily life, but now they have a nostalgic magic that he finds irresistible. They remind him of better times.

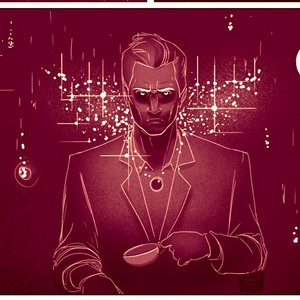

But the most inspiring thing of all to a young Spectro was Ibis the Invincible. He was an immortal. He was older than the Earth. He was older than the sun. In his aeons-long existence he had been Perkun of Pangea, Cadmus of Thebes, Pharaoh Akenhaten, and Apollonius of Tyana. In the late 19th century, he emerged from an amber-colored sarcophagus called the Creche of Hausus. He arose from stone marked with the oldest inscriptions on Earth--their meaning forgotten even by the one that chiseled them. He stood in the electric light of a modern museum like a mummy without bandages--his body unmarred and perfectly healthy.

He took the name Aiwass and joined the side of Aleister Crowley’s Hermetics against Annie Besant’s Theosophists in the Shadow War of 1899. Afterwards, he joined Crowley’s Circled Square under the trump of the Sun and worked to repair the fractured tradition of thaumaturgy and spread it to all mankind.

Putting the Shadow War behind him, Aiwass took the name Ibis after spending time in Egypt and remembering his life as Akhenaten. He always liked the bird and the Ibis-headed god of knowledge Thoth. He kept a pond of them as pets as Akhenaten--a fact lost to history until he remembered it.

As Ibis, he wanted to be an entertainer. He wanted to sell the idea of thaumaturgy to the masses.

One of the causes of the Great War in the Air was that the powerful nations of Earth felt unsure of their standing against the Circled Square and the rise in thaumaturgy they represented. They indoctrinated their subjects into believing that a population with individuals capable of working miracles was an anarchic and self-destructive society. The only way to prevent this mass anarchy was with a powerful state. And a state could only be powerful if it dominated its neighbors. Thus the fuse was set for an explosion that would go off when Germany, erroneously believing itself to be the only power with a fleet of airships, launched an attack on the United States in 1914.

Ibis hoped to dispel the world’s fear of thaumaturgy through mass entertainment. He would take thaumaturgy out of occult circles and put it on public display. Thought-forms and magic spells would leave the shadows and be put on bright stages.

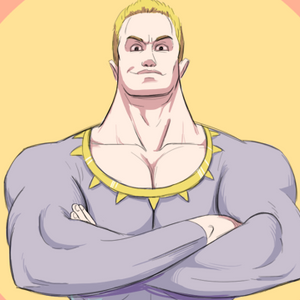

In the form of a kindly gentleman in a suit and turban, he toured the world putting on displays of thaumaturgy. What Wilbur Link was to robotics and Jason Gridley was to distant cultures, Ibis was to thaumaturgy. He de-mystified mysticism until thaumaturgy was no more frightening to mankind than electricity or automobiles.

Compared to other superhumans of the time, Ibis lacked a certain popular appeal. He wasn’t as reassuringly mighty as Gold Star, invincible man of light and power. Nor was he as personable and charismatic as superhuman police sergeant Dan Garret aka the Blue Beetle. Ibis was like a living history book. Ibis was half-translated texts and barely-recalled memories. He was history incarnate, and history will always be somewhat alienating to those that have to live in the here-and-now.

But that was what Spectro loved about him. Spectro loved that Ibis had forgotten more than he would ever remember. He loved how he made his identity out of palimpsest personalities. He loved how he spent his free time meditating on ancient texts and writing what he remembered about them in a journal called Tablets.

Tablets was a journal read by anthropologists, psychologists, historians--and a young Spectro who read copies at the library while his friends read Sultans of Gold and Dream Diaries of Randolph Carter at the local drugstore. Tablets has often been described as psychologically interesting but of dubious historical value. Ibis freely admits to having a fluid memory and his stance on a text can change issue by issue. He can go from believing he wrote a 14th century BCE text on the Egyptian afterlife as pharaoh Akhenaten, to believing that the text was written by another man using his name for the prestige it carried, to believing that the text was misdated by centuries and that he in fact wrote it in the 1st century CE as Apollonius in an attempt to remember being Akhenaten, and then back to believing that he wrote text as Akhenaten--all in the span of a few journals. Such was his memory that he often misremembered more than he remembered.

But Spectro found Tablets irresistibly interesting even as his friends teased him for reading something even their parents found dry and academic. He found the journals human in a way Jason Gridley’s reports and Wilbur Link’s toys weren’t. He collected every one with his allowance and to this day keeps them in his library yellow and faded though they might be.

Spectro’s interest in how people thought and behaved didn’t start with the vow he made after regretting erasing his name. He neve cared much to talk to people, but he always tried to know them as much as possible.

When Ibis came to put on a show in Spectro’s hometown of Little Rock, Arkansas, Spectro saved his meager allowance to buy a ticket. The show was full of vanishings and materializations and telepathy--things that the Spectro of today would have found quaint. But what Ibis told the audience that night set Spectro on the path he would follow for the rest of his life.

That night, Ibis decided to work in a speech during his performance about the often misunderstood subject of science and thaumaturgy.

Some of Spectro’s friends rolled their eyes and sighed as Ibis announced his speech at the end of his famous “moving painting” act where he tried to paint a portrait that fought him every brushstroke of the way, but Spectro was thrilled. He had questions about science and thaumaturgy, but being a child in a small southern town he didn’t know who to ask or how to phrase his questions.

Ibis began his speech by saying that that though attitudes on thaumaturgy had thawed considerably since the Great War in the Air (and here was where Ibis paused and pulled a rabbit with a tiny pickelhaube out of his turban--much to the relief of Spectro’s friends who feared the entertainment was over), people still clung to the erroneous dichotomy of science vs thaumaturgy. They believed that science was rational and static while thaumaturgy was irrational and ever-changing.

Spectro remembered some of his neighbors that believed in the dichotomy and for the first time in his life felt superior to adults. He remembered Ms. Grady, who ran the flower shop his mother worked at, who said that thaumaturgists changed their shape every hour--just because that was how thaumaturgists were. They couldn’t keep a single shape for long if they tried. And Mr. Sinclair who ran the neighborhood drugstore that Spectro bought candy from, said that thaumaturgists all had memories as spotty as Ibis because people weren’t made to plumb supernal realities. It was like staring at the sun or listening to gunfire. It eroded their minds starting with their memory and likely ending with their sanity.

It never seemed right to Spectro that people were so quick to condemn thaumaturgy as pure chaos. It couldn’t have been that chaotic. They had schools and teachers and books on thaumaturgy just like they had for every subject traditionally called science. There had to be some kind of structure to it, otherwise what would be the point of people talking about it at all? If it was all so chaotic then how come one name was all it took to describe it?

Ibis said that thaumaturgy was as valid science as chemistry or physics. It was true that compared to traditional sciences thaumaturgy had a unique subjective dimension. No single person observed and interacted with supernal realities the same way. A thought-form that rested as comfortably as a bird in a nest in one mind was a raging thunderstorm in another. A spell performed by this person had this effect but when performed by that person had that effect.

But thaumaturgy still followed the same scientific methodology of making hypotheses based on observations and testing those hypotheses to form theories based on replicable outcomes. Thaumaturgy was still a science.

Ibis gently levitated the audience in their seats and revolved them around the stage in a merry-go-round pattern. He said that this is what many thought the world was becoming with the spread of thaumaturgy--a world where no one could see eye-to-eye and no one stood on the same ground.

He spun the seats a little faster. All the children in the audience shouted as if they were on a carnival ride except for Spectro who like the adults understood what Ibis was saying and how important it was to the world.

Ibis said that many feared the world would become a world without truth. They feared that thaumaturgy would suck meaning and purpose out of the world and leave a shell called the post-rational world, postmodern world, or premodern world--for it would be one where man could no more be sure of his world or his place in it than when he sacrificed crops to the stars in the faint hope that the weather would be merciful.

Ibis then slowed the seats and brought them brought them closer around the stage in a circle that rotated slowly and orderly like the orbits of stars.

Science, he explained, was never about knowing a single, static truth. It was never about knowing to begin with. It was about seeing. Science never claimed to know what was absolutely true. Such claims were only made by ill-informed men drunk on the rush of power 20th century technology gave the human race. Science only ever claimed replicable and demonstrable outcomes to variable-based experiments. New observations changed scientific conclusions all the time.

To make his point, Ibis asked the audience what color the auditorium was. When the audience answered red because of the curtains and walls, Ibis snapped his fingers and caused the auditorium from its floor to its ceiling to turn bright clover green. Even the audience, to their amusement, turned green from their skin to their clothes.

Ever the showman, Ibis asked the audience to please withhold their envy at his phenomenal cosmic powers.

Ibis repeated his question and when the audience answered that the auditorium was green he snapped his fingers again and turned it a chilly frost blue. He repeated his question, and when the audience answered blue he repeated their exchange with a sunny daffodil yellow, then a warm sunset red, and a royal purple.

Ibis said that this was how traditional scientists conducted observations. They observed something changing out in the world and tried to draw conclusions. When observations changed, so did conclusions.

He asked the audience to engage in a little science with him. He asked the audience what they thought they could do to change the variable out in the world causing the colors to change.

After a moment, a man in the audience shouted “Hey Ibis! Change the color so it’s like a movie!” And then in a moment, added “...Please?”

Ibis smiled and in an instant the auditorium became black and white like a film. The audience’s skin became silvery grey and their clothes inky black.

Spectro felt a little jealous of the man that answered. He knew the answer but he didn’t answer. He overthought the question. He thought there was a trick to it.

Ibis snapped his fingers again and asked the audience what color the auditorium was now. The audience members were amazed to hear their neighbors shout out colors they didn’t see. Spectro himself saw a powder blue--his favorite color-- but heard green, blue, light-gray, and all kinds of colors.

Ibis snapped his fingers and brought the auditorium’s natural color back. He explained that what the audience saw was how the science of thaumaturgy conducted observations. Thaumaturgists observed something changing in their own subjective world and tried to draw conclusions. Again, when observations changed, so did conclusions.

Ibis invited the audience to participate in a thaumaturgical experiment. Everyone could do science--thaumaturgy was no exception. First they were to note the color of the auditorium as it appeared to them. This was their control. Then they were to change a variable and see what happened--the variable in this case being their will.

He told them to put forth a mental effort and paint the auditorium whatever colors they wished.

The auditorium erupted in cheers and laughter and surprised gasps. No one could see how his neighbor painted the world around him but no one seemed to mind. They made shapes in the air. They painted their friends like clowns. They did nothing and took amusement in watching everyone else make faces at the walls of a normal auditorium.

Spectro was puzzled to find that the auditorium didn’t change for him. It remained the same powder blue it was before. He figured he must have had a very strong will to passively exert a degree of control over Ibis’ spell--his mother always said he was a wilful child.

Spectro had no idea how strong his will really was. He had no idea what he had the potential to do if he only understood how to apply his will.

Unconsciously cast or not, Spectro worked his first spell in that auditorium.

Comments (0)

See all