I have never seen Shay angry.

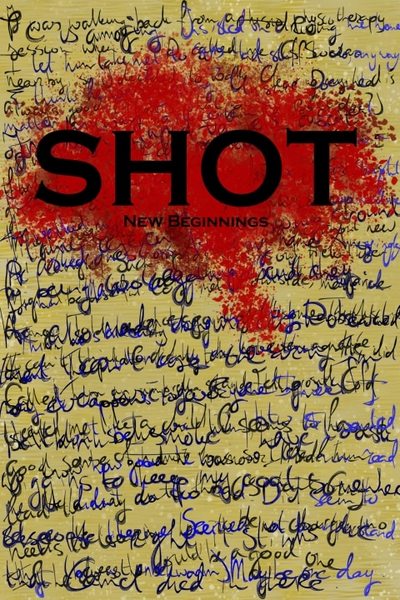

I thought I had, but then Peter regaled me with a story he’d sworn to never tell, and I promised to never pass on. But, it’s three in the morning, he’s left his notebook in my possession, and I’m bored and curious and a strong believer that every story should be told. Especially one like this.

It started as a semi-regular case. I remember the first day of it; I’d come into work only to find it almost deserted. Carlyle informed me that they’d had a phone call around seven that morning, and they’d sped out with nary a word. It would happen sometimes; they’d be called out in the middle of the night, or early in the morning, and they’d rush to get ready and out the door, talking about urgencies and rain washing away tracks, already speculating as they flurried through the house. But on those days, Carlyle would have an amused glint in his eyes, picking after them with fondness.

That morning, there was nothing like that. There was a resigned sadness in his eyes, a grim set to his jaw, a tenseness in his muscles that seemed hard to shake. They were rare, those mornings, and they’d often spell days of thunder and darkness and difficulty. A look that could only mean one thing.

Carlyle confirmed it, with three pained words:

“It’s a kid.”

It’s always harder when there are kids involved. Hours were longer, nights were shorter, and no one rested until there was some sort of resolution, and often it left a bad taste for weeks after. Oftentimes, they called her is as soon as they got the alert, not wasting any time on useless things like protocol or preserving dignity. This time, there’d been a car waiting for them by the time they got ready.

A seven-year-old boy, Chase, had disappeared from his bedroom. His bed was made, his window locked, his lain-out clothes untouched.

They surveyed the scene from the doorway, Chase’s mother standing right behind them, nervous. There was something she saw in that room, something that made her frown deeply, her face only darkening as she inspected drawers and cupboards and opened the wardrobe.

“I’d like to see your bedroom, please.” She barely glanced at the mother as she pushed past her, marching across the hall.

Chase’s father blocked her way, though, with his broad body. He wasn’t tall, barely four or five inches taller than Shay, but it was enough to loom over her. She seemed unimpressed.

“Sir, please-”

“Don’t you need a warrant or something to prance around the place?”

“Not if you let me pass.” Peter was standing at her back, but the glower she gave him was undoubtedly impressive. “Sir.”

“I don’t have to-”

“But most people do, considering I’m looking for their kids.” Peter could hear her glare in her voice. It was beginning to get that icy quality that meant she was one wrong word away from pulling rank and verbally pushing him out of the way.

He’d let her, in this case.

The man stepped aside, though.

She nodded, “If you don’t want to watch me root through your stuff, I suggest you wait outside.”

“You insolent little-”

She caught his wrist before his fist could gain enough speed. Vaguely, Peter registered that she’d grabbed him with her right arm, knuckles while and thumb firmly pressed against the inside.

“I’d advise against that.” She dropped the hand, stared him down.

He couldn’t resist piping in. “Trying to punch a Special Forces vet would be a spectacularly bad idea, wouldn’t it?”

Realisation dawned, like a bucket of ice. “Yes.” He stepped back, in the direction of the stairs, the direction of outside. “Yeah, it would.”

Shay pushed past them, into the bedroom. Chase’s mother followed, agitated.

“Close the door.” She glanced back at Peter, something stormy in her eyes. He did.

She moved to one of the walls, where a handful of picture frames were reflecting the sun. “Tell me,” She started, studying the frames, “Tell me if there’s somewhere I shouldn’t look.”

“Oh, I.” The woman seemed startled that the gruff, quiet detective was suddenly talking to her. “Ehm. There are some… things in the bedside drawer.”

“Got it.” She pointed at one photo. “Who’s the girl?”

“Oh, she’s my daughter.” Chase’s mother smiled, “Clarissa. She moved out last year, has a job in Slough.”

“From a previous relationship?” She snapped a picture of the photo. “She’s a bit older than Chase, no?”

“Her father and I separated when she was three.” She looked wistful. “We were alone for a long time before I met Chase’s dad.”

“Do you have her address?”

“Of course.” She dug through a drawer, pulled a booklet from beneath a stack of drawings. “Are you going to visit her?”

“We might.” She glanced at the page the woman held out to her, took a picture. “If we see reason to.”

Her hand shot out, grabbed Shay by the wrist suddenly and tightly, like a castaway clinging to a lone piece of wood.

“You will find my son, won’t you?” There were tears in her eyes, desperation in her voice. “Please, Doctor Klinger, you need to.”

She swallowed, face as neutral as she could get it. Peter could see the indecision in her eyes, though, the urge to make a promise she might not be able to keep.

“I need to take a look at your fridge.”

“Okay, shoot.” Peter started as soon as they were in the cab, on their way to Slough. “You’ve been on edge since we got here. Tell me why.”

(There is a certain direct approach that the Caryles can get away with that no one else could ever dream of. There’s no warming up, no skirting around the subject, and, surprisingly enough, barely any shouting matches. I envy them.)

She leaned forward to close the partition. “Child abduction case, Pete.”

“More on edge. And now we’re headed to Slough. Come on.”

She thought for a moment. He let her.

(We’ve all learned to let her, at some point or another.)

“What would you do,” Her voice was soft in the small space, “if you visited Betts one day, and May cowered behind her, and their arms were bruised?”

A certain feeling of dread settled in his stomach. “I would kill whoever did that, ‘cause Morgan would never.”

“I know.” She fumbled with her phone, pulled up the photograph. “But what if he did?”

“You think the dad’s abusive?” He tried to fit it into what he already knew. “Why?”

“Tell me what you see.” She gave him the phone. “Take your time, we have an hour.”

Whenever she’d say something like that, it would pay to do as she said, so he looked.

It seemed like an ordinary family photo, the four of them standing, smiling, on some sort of beach, backlit by a clear blue sky.

“It-”

“Look at her. Tell me what you see.”

He looked again, better. “The mother is wearing long sleeves.” He noted. “So is Clarissa. It’s summer.” His eyes looked down at the boy. “He’s not.”

“Look at her hand on his shoulder.”

He did, but he knew he was missing something. The hand was just there, resting on the boy’s shoulder, thumb loosely hooked behind the base of his neck.

She guided him through. “Think about how you’d put a hand on someone’s shoulder.” She prompted. He realised. Not like that.

“Now think about who you’d hold like that.”

He met her eyes in silent understanding. He didn’t want to answer her, though, because he knew it was already clear in his gaze; You.

(The way he touches her is always so gentle, so considerate, all soft pats and gentle bumps and comforting hugs. It stood in stark contrast to the way he roughhouses his sister, the way he twists her arm and calls her an idiot. Instead, it’s come here, idiot and an opportunity to hide from the world.)

“It’s flimsy.” He pulled a face.

“I know.” She shrugged, sad. “But you asked what was wrong.” She curled up on herself, turned to the window, retreated into herself. Conversation over, apparently. Peter was fine with it; silence is not a rare thing with Shay, and they still had plenty of time before they arrived in Slough. He wouldn’t be surprised if she snuck in a nap before they got there.

(And neither would I; for a person who’s always on guard, she falls asleep surprisingly easy, and she’ll sleep everywhere. I found her snoring stood up against the door to my office, once.)

She stirred, cracked one eye open before she fully let herself slip.

“I need you to not believe me.”

He couldn’t help but smile. “I know.”

Comments (0)

See all