Loud music filled the room, making it hard to hear anything else. But that was the point.

In the early days, I couldn’t understand why my older brother would shut himself in his bedroom blasting his alt-rock so loud that the floor shook. They didn’t know then that children and infants couldn’t hear it. Some underdevelopment in the temporal lobe.

At eleven, I asked him to describe it to me. He said it was a low, constant droll. He said if he didn’t block it out, it would burrow so deep in his ears that he thought his brain would pop. “It’s like water pressure when you dive too low in the deep end,” he said.

It sounded to me like a lot of dramatics just to get out of going to the corner store. But then, he was like that.

They prescribed him focus pills and his teachers said he had an anger problem. Too much video games and Youtube. Him and his whole generation, it seemed. It was no surprise when the teenagers in town all came down with ADHD at the same time. The pharmaceutical companies must have thought they’d struck gold. In the end, it was the tech companies that won.

Royce pushed me out of his room and shut the door.

I didn’t mind. It meant that I could go alone and use the extra change to buy candy, and my friends and I could smoke cigarettes in the alley behind the laundromat.

“Bring your sister,” my mom said.

“What?” I pretended not to hear her over the television. All day long, my grandpa had the news going on high. Between his stories and my brother’s music, you couldn’t hear a train if it ran straight through the house.

“You’re taking Harley,” my mom said, coming so close that I could count the lines on her forehead. There were enough that I knew not to test her. “And don’t forget the Advil—two bottles.” She handed me a list and some cash.

“And if they’re out?”

“Just…” She pressed a spot between her eyes. “Whatever they have.”

My mother went through headache pills like my grandfather went through cigarettes. As I passed him in the living room, he handed me a five and asked me to pick him up a pack.

At the door, Harley stalled and I rolled my eyes. “Come on,” I groaned.

She was holding the screen open for Benjamin Bones to come out and do his business. The old hound didn’t move but lay in his doggy bed, shaking his head to ward off invisible flies before burrowing down into the cushions again.

“Let’s go, Harley.”

“Come out, Benny!” My sister urged.

“He’s not interested, Harley.”

From inside, my mom shouted to close the door and Harley let the screen clatter shut.

The earliest reports on the Humming would say that it started in the rural areas, the small ranch communities and farm towns on the outskirts of civilization. They said it had something to do with how isolated and out in the open we all were. As if we could have hidden from it.

Really, it started in the cities. You just couldn’t hear it over the noise.

As we rode our bikes down the barren streets, my sister and I soon had company. One by one, my friends peeled from their houses, each with their own parcels and instructions.

It was one of those small towns where everyone knew each other and all the kids for miles were somehow the same age. There was one school there and as many dirt roads as asphalt, and if you sat still long enough you could feel the silence throbbing in your ears. Unlike the cities, whose ceaseless outcry of machinery and progress left no gaps for quiet, our small town still had long roomy stretches of it, enough for something else to soon settle in.

At first, it was described as a low, constant buzzing, like a swarm of flies in the distance. But no entomologist would ever place it to any known species of insect. When our town first caught it, all we did was turn up our televisions and switch our fans on high. Long conditioned to a little discomfort, we didn’t make a fuss over things we couldn’t see. Complaining was for the big city people.

Like escaped convicts, we ducked low on our bikes and raced the main streets, feeling blessed with barren roads. With everyone barricaded in their houses, the only life to be seen were the few stray cats that darted into bushes and the dogs that had been put out. My mother always said it was cruel to keep a dog chained up outside like that. They forgot their manners and grew unsociable. They watched us pass and I looked into each scruffy face and saw an artsiness I recognized.

Benjamin Bones had been growing restless over the last few weeks. The vet, who was getting a lot of the same kinds of calls lately, said that the dog was only agitated by the season change and that if we crushed up some allergy medicine in his food, old Ben would be fine. He’d said not to worry and I didn’t. Even as Harley had taken to watching the dog for long periods with a consternated look on her face, I didn’t worry.

On the way back, we stopped in the alley behind the landromat. If my grandfather ever noticed that his packs were always one-short, he never said anything. I told Harley to go keep watch at the mouth, though there wasn’t any need. The strip was as dead as the neighborhoods. So, it was with sweet inconsequence that my friends and I teased one another, coughing more than we inhaled. We didn’t notice our shadows, dancing and laughing, rippling across the gravel as they slipped from the bottoms of our shoes and down the alley, away from us.

Home was always a slow ride, the streets cooled by dusk. From outside, my house always looked darker.

In the kitchen, my mom was on the phone, likely with an aunt up North. She called there more often lately and I would overhear her speaking in hushed, hectic tones in the parlor. Sometimes it was about Royce, about how he wasn’t getting any better. Sometimes, it was about money and how she couldn’t take any more sick days. Sometimes, it was about the town and how lately, something just felt off.

Even if I’d known then what it was all really about, I still wouldn’t have stayed to listen. In fact, I would have left even faster. I dropped off the pills and groceries on the counter and once more darted for the exit, before anyone could find reason to keep me indoors any longer. I passed my brother’s bedroom and the muffled howls within. I passed the dog whining softly to himself in the corner, and the little girl sitting cross-legged watching him. I passed my grandfather still parked in his armchair in the living room. Still, I didn’t stop— wouldn’t— not until I was out the door and a wide distance from that dark house of noise and silence. Still, even as I gained ground, I caught a few lines from the news report my grandfather was watching.

“… And up next: Ouch! Don’t pet Whiskers! Reports of a recent rise in the number of feral cats in the area. Local veterinarians warn of a possible rabies outbreak. They remind owners to keep up with their annual shots, and urge parents not to let little Tommy pet strange cats…”

It faded into the general noise of the neighborhood. At the center of which, I found my friends waiting for me. From all directions, the garbled sounds of competing televisions, radios, and phone calls could be heard blaring from every home along the street. No one broadcast mentioned the Humming and yet all of them did. It wouldn’t be named for another few years, but in the meantime, it was in everything. In every news item, every police report, every sick-leave, every neighborly dispute, the Humming was at the root.

But between the houses, amidst the giggling and whispers of my friends an I, it was nowhere to be seen.

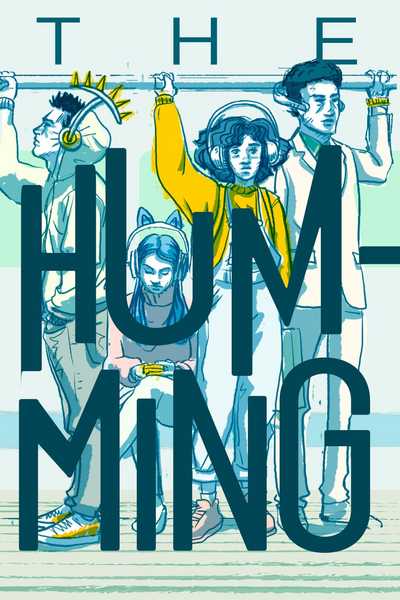

On those empty streets, we played like we’d stumbled upon an endless summer. We laughed louder, skipped higher. There were no cars to interrupt our chalk murals, no parents to call out that we settle down or to give us wide eyes when we cursed. We were an island of kids, raucous and free, untethered by the faraway problems of a world that didn’t concern us. We were the special ones, the ones who didn’t hear The Humming.

A year later, when it finally caught up with us—or rather, we caught up with it— it overtook our little circle like a slow infection. One by one, we each receded to the indoors we’d avoided for so long. Like my brother, I too shut myself away. I couldn’t get the music loud enough. But by then, the Humming too had grown.

It would be decades later when they came up with the official rating scale, but it was about that time that we hit what is now known as Tier Two, where it gained its namesake. No more the low, barely discernible rumbling in the distance, now the unidentified sound had grown to a clear and continuous tone— a humming.

It was around that time too that all the dogs in town started going crazy.

Comments (1)

See all