“This is where you’ve been staying? How long? I—” I step further into the small motel room. “—I’m kind of disappointed.” I admit.

“When you’ve been at this for as long as I have,” Death shuts the door behind us, “you learn not to need much.”

There’s a difference between not needing much and not needing anything. The only commodity besides the two beds is the TV. It’ll be a pleasant surprise if it turns out to be in color. An even bigger one will be if it works at all, given the bow-shaped state of its antenna.

Why are all wallpaper patterns of flowers? Are motels supposed to make you feel like you’re at your grandparents’ house? This place looks the type of joint Johns bring along the little secrets they don’t want their wives to know about. Is fucking hookers supposed to feel homely? Has the culture changed?

I sit on one of the beds. “You should probably get rid of the car.”

Deaths sits next to me. “It will find its way to the junkyard, one way or another.” They throw the scythe onto the ground. “Please, just think about it. I’m asking you not to make this difficult. I’m not your enemy. There isn’t an enemy to even be looking for.”

“I’m not changing my mind.” I say simply.

“Nobody can see into the future.”

“If you’re as desperate as you’re making yourself out to be, you’ll get tired of waiting. Maybe go off and knock up someone else. Try again.”

“I don’t want to do that.”

I grab the TV remote. “Seems to me like you’re not having much luck with getting what you want.”

“I can wait.”

“We’ll see.”

Year One

—hanks, John. I am standing outside the Mayfield Town Square, where protestors have gathered in opposition of the Mayor’s promise to install checkpoints between three of the city’s largest boroughs, citing the increased crime rate as the core reason. Opposers claim that the appearance of national guards within cities is the first step to restricting individual freedoms, citing the incident in Richmond earlier this year as—

Death lays on their bed. “I told you. People don’t… experience me as I really am. To them, I look like—”

“It doesn’t matter what you look like. She wouldn’t have slept with you if you were a young Brad Pitt. What did you do? What did you tell her? Did you mind control her?”

“If I could control minds, we wouldn’t be having this conversation, to say the least.” They sigh. “We met right after I realized I couldn’t keep going as I was. The spill had just happened, and I just—” They look at me. “I was trying to keep my mind off of everything. I decided to paint. I joined a—a little art class.”

“You’re shitting me.”

“What’s wrong with that? I was trying to mingle with people. There was no plan on my mind. You weren’t on my mind. I was just trying to make up for the—the loneliness, I guess. And I met her. She was sweet. She was. Funny. I liked her.”

“And, what? You just started seeing each other?”

“More or less, yes.”

I get up. “Screw you.”

“I don’t know what you want me to tell you.”

“I want you to tell me the truth.”

“That is the truth. Whether or not you accept it is none of my concern. Whatever you saw – whatever you remember – was all after all this. You have only your parents’ own word as to the lives they had before then.”

“She loved Dad.”

“Clearly, given that she ended it the moment she found out she was pregnant.”

I clench my fist. “Made things easier for you, I guess.”

“Yes.” they say. “Yes, it did.”

Year Two

—eaking News here, Tom. After a shocking vote, the Senate has announced that they will follow the example set in Mayfield and install an outpost for the national guard in several major cities. This come as an even bigger shock after Senator Folker stated she would not be voting in favor of the motion. The protestors behind me are rallying, you can hear th—

Death glances up from their book. “You’ll walk down the road, inevitably get to a rest stop or gas station or what it is they have here and inevitably turn back around. How many times have we done this now? I don’t even need to follow you anymore. You’re doing my job for me.” Their attention turns back to the page. “Still, if you do manage to get further, I’ll know where to find you.”

I open the door.

Year Three

—ther news tonight, a local caretaker here in the quiet town of Palmwood Springs claims that he has witnessed a corpse walk out of its grave. The body of deceased Martin Shepard is indeed missing from its grave, but authorities, however, insist that it is likely the result of vandals. The caretaker, however, insists that he saw a—

I finally make my decision. “Knight to E4. Check.”

“You can’t.” Death tells me.

“Why not?”

They point to the chessboard. “Because now you’re leaving a clear line for my rook to your king. You can’t.”

I flip the board over. One of the pawns hits me in the face. I pretend not to mind.

“You know,” Death leans back in their seat, “I have the power to know where every soul still present on Earth resides. If you were to take over, finding Miss Selene would be a cinch.”

“I don’t care where she is.” I say.

“That is a lie. You went to an internet café the other day. You looked her up. Don’t even bother denying it.” The diver leans their helmet against hand. “Did you like what you saw? Were you attracted to her? I’m genuinely curious if you’re still capable of attraction.”

“She looked fine.” I move over to my bed. “I’d seen her face before. When she was moving into the body you saw her in.” I didn’t, though. When she was left Ferdinand’s body, it felt like watching a woman change. Inappropriate.

I’d never imagined her to have freckles. Or that hair. Or that nose. Her eyes were smaller, too. Lips fuller. The only face I’d thought about all these years has been Abigail. It’s going to be difficult to see her as anything but that.

She was cute, though. When she was Selene. Freckles and everything.

Where is she now?

Has she changed into something else? Has she found another body?

Does she think about me?

Year Seven

—emind everyone that the new curfew rules go into effect tonight at midnight. Guard patrols begin at 2 AM, and any citizens found outside after that point without their valid permit may be taken into custody and face fines up to two thousand dollars. We’re seeing reports of streetlamps being vandalized, likely in some form of effort to make the guard patrols that more difficult. The authorities note that this behavior puts not only guards, but the citizens at risk, as well. Joining us tonight is the head of—

I’m lying on the ground. This body has no need for sleep. I haven’t slept in years. It can’t feel exhaustion. I’ve hardly even done much to warrant feeling exhausted.

Even so, I yearn for sleep.

Even so, I’m getting tired.

Ferdinand doesn’t seem to share these troubles with me. He’s trucking along, as he always has.

“What’s the average life expectancy for hamsters?” I ask, staring into the cage.

“Three years, usually. I’ve been meaning to talk to you about that. Weird hamster you got there.” Death says from the bathroom. I can hear the sound of metal scraping. It’s driving me nuts.

I look to the bathroom door. “The hell are you doing in there? It’s been, like, two hours.”

“I’m shaving.” comes from the other side.

“You’re—Excuse me?”

“You heard me.”

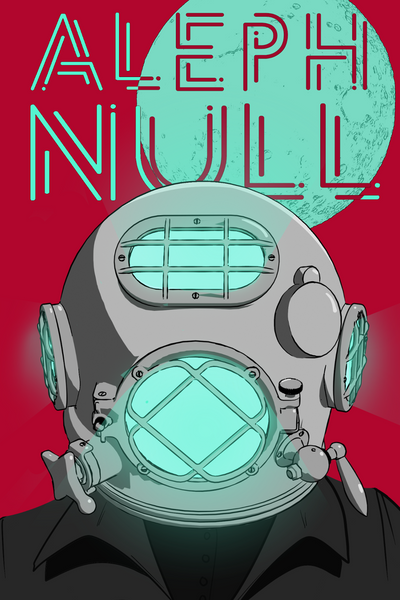

“Like, you took off the diving suit? I didn’t even know you had hair—”

“No, the suit’s still on.”

“The fuck?”

“There’s something on it. I don’t know what it is. Looks mold-y. Can mold get on these things?”

“I figure you’d know better than me.”

“I know of all things life and death that someone in my position can know. I know nothing about mold. Or old diving suits.”

“You know,” I get back on my feet, “what’s the deal with the suit, anyway?”

“Nothing to it. I just needed something to hide my appearance. I usually change it up every few decades. I’m a bit late with this one, I guess. It’s just convenient.”

That is convenient?

“It belonged to a man called Jeremiah Stone.” they explain. “He was enticed by legends of sea monsters. His favorite one was the one about half-men-half-octopi. He believed they slumbered deep underneath what you’d now call The Bermuda Triangle. So, he drove his little boat out there, put this suit on, and dove.”

I grab some more food for Ferdinand. “And?”

“And nothing. He underestimated the depths. He was a village boy whose only knowledge of the sea came from his cousin fisherman. The pressure got to him. Passed out, ran out of oxygen. Was found exactly where he’d left himself. Found by me, that is.”

“That story intrigued you so much that you took the suit?” I put the food in its slot.

“No. I took the suit. Went further down and found Jeremiah’s ship. The ship had his journal.”

“What were you doing so deep?”

Death chuckles. “Searching for the half-man-half-octopi, of course.”

Year Ten

—as been arrested for the murder of Congressman Dean Hurst after a scandalious leak. He maintains his innocence, with his lawyers claiming that the culprits were a group of men wearing animal masks. Is it the truth? Is it lies? We dive deeper into the case. Tonight! On Crimes of th—

“Where did you get that?” Death asks me.

“It was in the Fiat’s glove compartment.” I place the revolver on the table. “You still haven’t gotten rid of it, by the way.”

“I think it’s safe to say that nobody has any interest in finding it.” they sit across me. “I’m hoping you’re not considering shooting me.”

“If I was as naïve as that, I would’ve actually managed to leave.” I pick the revolver up. “Fancy a game of harmless Russian Roulette?”

“The other guests will be disturbed.”

“There are no other guests.” I point out. “In fact, I’m pretty sure this place went under five years ago.”

“TV’s still on, though.” Death notes.

“I keep siphoning gas from the car into the backup generator.” I admit.

“And where does the Fiat get its gas?”

“From the gas station three miles down.”

“And where do you get money for said gas?”

“I don’t.” I pull five of the six bullets from their chambers. “Any more questions.”

“No. I guess not.” they shrug. “See? The car has its uses.”

I spin the cylinder. “You first.”

Year Fifteen

—ity is reeling with shock, after Mayor Wellgreen, hours after being pronounced dead, woke up on the autopsy tabl—

“You said you know where everyone in the world is.” I say. “What about Mom? Where is she? Is she still out there? She’s gotta be, right?”

“I can’t tell you that.” they say.

“Won’t.”

“Same difference, in the end.”

Year Seventeen

—eports of a new, sudden candidate in the local election: a man with—bzzt—for a hea—bzzt—

I punch them in the helmet. The metal reverberates, but does little to throw them off their posture. Their punch, on the other hand, sends me flying across the room. As I slam into the wall, the paper finally tears.

I reach for the scythe on the ground. “Just leave me alone already!”

“I can’t. You’re my only chance be happy.”

“You don’t know the meaning of the fucking word!”

“I can learn.”

I swing.

I miss.

They take the scythe from my hands and smack me upside the head. I fall to the ground.

“You done?” they ask.

I don’t get up.

“You’re done.” they conclude.

Year Eighteen

—bzzt—bzzt—bzzt—bzzt—bzzt—

"TV finally gave in, huh?" Death asks.

"Even if it hadn't, it wasn't long for this world." I say. "That gas station's abandoned. In a hurry, too. The kind of hurry that doesn't leave behind any gas. Bit eerie, I guess." I stretch. "Oh, well. There goes the last reason to go out."

"Things do feel strangely quiet."

"Yes. Because the TV's out, genius." I point out.

Year Nineteen

We’re standing on the roof. Each with an easel in front of them, trying to capture the sunset. Death’s way better at it than I am. I guess they weren’t lying about the art class.

“I got hit by a car once.” I bring up, in an attempt to distract myself from how smudged and messy my trees are looking. “Gave me the metal plate.”

“I know.” Death says.

“A few days after I got out of the hospital, the police showed up. They wanted to question Dad. Apparently, someone had attacked the driver of the car. Gouged his left eye out.”

“I remember.”

“Do you?”

“I was annoyed. I felt the need to punish, so I did.” They dip their brush into the little cup of water. “Sure, I needed you to die. But not to be stuck with the mind of a child in your form. Not only would I have to start again, I’d have to deal with a fallout of something like you on the loose. Sure, you lived. But it didn’t change the fact you might not have. I didn’t like that. Not one bit.”

“I. See.”

“I’m asking you to take my role for what will likely last as long as humans exist. Or whatever counterpart with a soul they evolve to. I know I am cruel. I know I am selfish. I know this is not fair. And you should know that I do not want you to suffer. It has never been my intention. I do not hate you. I am not even entirely indifferent to you.”

“What are you, then?”

“I told you. Tired.”

I chuckle. “You know, in the time we’ve been here, you could’ve fixed that spill fifty times.”

“And when the next one came? And the one after that? And the one after that? Was I supposed to look for a successor in the quiet times? Do interviews?” They shake their head. “Besides, in the time you’ve spent defying me, you could’ve taken up my mantle, and nothing would’ve changed. You’re an eternal being stagnating in a motel room. The only thing accepting would do is give you an occasional chore to do. If anything, it is a bonus.”

“You’re not any better.”

“No, what I am is different. All I’ve ever known has been this task and purposeless meandering through this Earth, never being able to seek out something more. You, on the other hand, have spent your whole life seeking. And time and time again, you’ve left the places you’ve found yourself in. Nothing has ever been good enough. You being stuck here feels no different than usual, does it? Even after all these years. Because you’ve found that nothing works. You’re a key without a lock. Yet here I am, offering you the lock. To do what you were made to do. It is, if nothing else, better than nothing.”

“Made to do, huh.” I put my brush away. “Did you do this to me? Did you make me like this by design?”

“No.” they say.

“So, alright. What happens to you when I accept? What will you do? How does all that meandering become purposeful? If your ambition is to paint, then I don’t see what all the fuss has been about. Nothing’s stopped you from blending in with the world so far, from what you’ve told me.”

“To blend in means that the ones around you accept that you are who you present yourself as. To be free is for you to accept that you are who you tell others you are. I want to be free.”

“Not being this doesn’t mean you’re just suddenly human.”

“It means I’m not above them. That is good enough for me.”

They step away. “My painting looks like trash.”

I shrug. “Better than mine, at least.”

I look to the sunset.

“Okay.” I say.

“Okay, what?”

“Okay. I’ll do it.”

Comments (3)

See all