Then there was her public support. Given all of the above, it suddenly seemed far more plausible that she’d simply been a genuinely good person caught up in a horrible situation who had navigated her way out as best she was able. In February 1975, a group of 30-plus people formed the Jannie Duncan Freedom Committee, raising money and circulating a petition seeking her release; they collected 5,000 signatures. Friends recruited the support of D.C. Councilwoman Willie Hardy and Walter Fauntroy, a prominent politician, pastor and civil rights advocate. More than 20 friends and employers offered to provide character statements in court on Jannie’s behalf.

Silbert was the U.S. attorney in Washington then, so he wasn’t necessarily in the business of letting people out of prison early. His response to her parole request is a pitch-perfect coda to Jannie’s uncommon odyssey. It’s obvious, reading between the lines, that he struggled to reconcile the particulars of her story, which he characterized as “a somewhat singular case.” Her interactions in her jobs over her 12 years as Joan Davis “reveal someone in whom these employers have complete trust and confidence and even more — as a person. In addition, this office has had contact with other members of the community who also demonstrate an equally high regard for Ms. Duncan. These comments cannot be lightly ignored. To the contrary, they are most persuasive.”

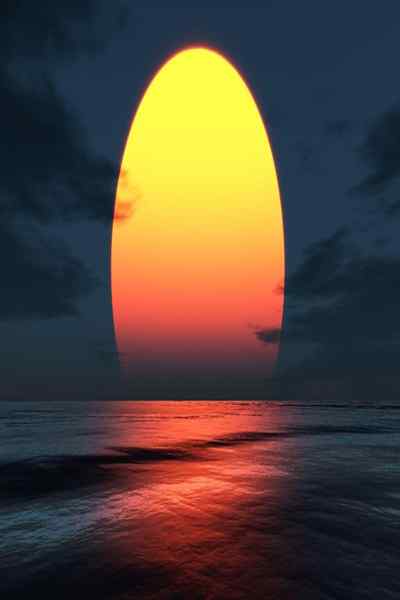

Jannie was released in April 1977. The Post showed up to cover her departure from prison, taking her picture for a front-page story headlined “The Saga of Jannie.” The subhead is notable for its Martin Luther King Jr. echo: “‘Lady in the Dark’ Is Free at Last.” She said she hoped to one day seek a presidential pardon and write a book about her ordeal. The friend who fetched her from prison suggested a title: “The Case that Rocked the Nation’s Capital.”(A Washington Post article showing Duncan leaving the detention center with her lawyer. Photo courtesy Washington Post Archives)

But after this brief bit of fanfare, she was never heard from publicly again. It was as if she dissolved into her post-prison life with all the anonymity and quasi-invisibility of her years as Joan Davis.

Her family is content to let her story fade out of memory. Jannie’s sole remaining close relative, a daughter now in her 60s, at first denied that Jannie was her mother. Shown evidence to the contrary, the woman replied that she preferred not to participate in this article. I subsequently sent her a draft of this story. “All I can say is WOW! She had more alias’ [sic] than ‘Mission Impossible,’” the daughter emailed back to me. “All this just explains a lot. I must commend you on the great details you uncovered. However this still does not change my mind. I’d rather remain silent and not open up old wounds.”

But one friend filled in Jannie’s final chapter. Lorraine Sterling, a friend from the Joan Davis years, kept in touch with her by phone after Sterling moved to North Carolina in the early 2000s. Sterling says Jannie lived quietly in Maryland after her release from prison, working and spending time with friends. She evinced no interest in garnering further attention. “She was a very loving and giving person,” Sterling says. “She had friends, but she kind of stayed to herself at times too.”

When Jannie became frail, her daughter moved her into a nursing home. She died in May 2009, at age 89, in Chevy Chase, Maryland. Her relatives held a quiet ceremony at Scott’s Funeral Home in Richmond on a warm May afternoon, then wended their way to the Washington Memorial Park and Mausoleums in Sandston, Virginia, near her birthplace, for the burial. The circle of her life was complete.

I understand her daughter’s impulse to pat down the earth over this complex tale. But as I exhumed Jannie Duncan’s full narrative, two things stood out. The first was that initial assumptions about people are often wrong. Mine were in this case — and in a time when we’re seemingly growing more alienated from each other, I was reminded to look deeper for the complexities inside all of us, our shared humanity.

And second: Jannie’s story is more relevant now than ever. She was a black woman who lacked power or standing while facing a justice system dominated by white men aligned against her. She was easy to brush aside; her telling was easy to dismiss and distort.

There are some lingering questions that may never be fully answered, but this much is now clear: Jannie was a survivor. And we know, after these last couple of years, that there are countless survivors today facing the same systemic hostility, the same biases, the same obstacles arrayed against them.

Finally, then: This is the story of Jannie Duncan, survivor. For her sake, and the sake of others whose lives were damaged by what happened one night in March 1956, it’s tragic that no one listened then, more than six decades ago. For the rest of us, it’s not too late.

What do you think?

David Howard is the author of two nonfiction books, including Chasing Phil: The Adventures

of Two Undercover Agents with the World’s Most Charming Con Man.

Comments (0)

See all