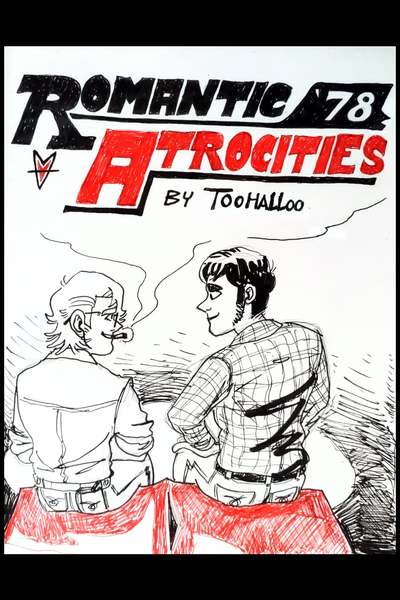

The Denny’s in West Virginia or Kentucky

It’s late May, 1997. It’s getting real close to June. My friend Roy and I are riding down the I-64 Eastbound towards Richmond on our way to Virginia Beach. He said there was something incredible there, or whatever, and I can easily imagine it’s at least better than Kansas City, MO, so I go with. And frankly, some hundreds of miles in, I’m still pissed that we’re even going on it. But I am less pissed than when I figured out we weren’t going for a trip to his dad’s house, so I guess I can take it..

We are best friends on this spontaneous trip, both 19 years old in his dad’s Firebird, and there’s been something burbling in my chest this whole time. I can’t yet name it.

I think we’re in West Virginia, and Roy seems to be convinced it’s actually still Kentucky. Neither of us can confirm until we hit the next stop. It is very late at night, but his dad didn’t opt for the clock in his red ‘78 Firebird, so we can't confirm the time either. The radio is on Best of the Oldies, motown hour.

“Hey, Allen,” he offers, one hand feel on the steering. “Anywhere to eat popping up?”

“Uh, yeah,” I say. “Hold on. I think we just passed a sign for Denny’s.”

“Rad,” he says. “What exit?”

We pull off, tired and hungry and borderline delirious. I won’t tell him this, but as he yanks up the parking brake, he looks like the coolest guy I’ve ever met. Blond hair, denim jacket, faded jeans. A cross on a beaded metal chain over his heart. Sunglasses tucked away in the front pocket.

Maybe I’m just tired, but…

He’s gorgeous.

I unbutton a few off my tucked-in flannel and lean back. To my left, Roy’s sparking up a joint.

“You want in, man?”

I’m too tired to say no.

He laughs, hands it to me lit, and says “I don’t think we’ve smoked together more than like, once.”

“I don’t do it often,” I say. “Geeze, Roy, I can’t believe we crossed state lines with this.”

He smiles, leans back, and says, “Live a little, Al.”

So I do.

I don’t choke on it, not like the first time (also with Roy), but it’s a struggle not to. We give it a while and it hits like a soft warm blanket in the night. Maybe this is why he was always out behind the bleachers doing this while I was running laps. Maybe I’m getting him, now.

And the conversation comes easier.

In about 45 minutes, we’re already at that point over a grand slam each inside the late-night restaurant.

The burbling in my chest gets a name.

“So, like,” I start. I can feel my eyes squinting. “Come on, man, you’re hot shit. All the girls know it. You’re the perfect bad boy type, why’d you never date anyone?”

He stops eating.

He bursts into laughter.

“Hey...” I mumble.

“You can’t figure it? Are you serious, Al?”

“What do you even mean?”

“You can’t really be asking me that, man. You’re my best friend!”

I smile sheepishly and say, “Yeah, you’re right. I know why.”

I’m hurt, and I’m lying, but I laugh too. Whatever. I take it as a sign to never, ever ask again. Except...

When we’ve paid in full, with tip:

When he leads me back to the car:

A big, aching sadness convinces me to go for gold. I take my seat beside his, in the passenger side of the ‘78 Firebird, and overcoming the bulky center glovebox…

I kiss him in the car.

Shock and awe don’t register. Just that strange ache, now even stronger, the solemn knowledge that this is the only way it’ll go for us. For me. The kicker is I can’t imagine kissing anyone but him. The kicker is that he can have any girl he wants, and chooses none.

The real kicker is, when I think this, he kisses back.

Henrico, VA

We had kissed each other in the Denny’s parking lot, mutual, about a day and 100 miles ago by this point. And in the driver's seat of my dad’s red 1978 Pontiac Firebird, Allen isn't speeding anymore, but he had been for the 20 miles prior. Going 90 on I-64, while I vent the overflow, and while he increasingly white-knuckles the wheel. Is he angry? It feels like it. I told him to cool it, ‘cuz it was making me dizzy. It’s unlike me, but maybe that’s why he slowed down.

“Hey, Al?”

Nothing. He turns the volume knob. The static-bearing local Oldies station gets louder. It’s Jimmy Ruffin this time, but I don’t know how I know that.

“Allen, d’ I ever tell you… You’re my rock?”

“Mm.”

Terse.

“I mean it,” I say, with a knot in my stomach as the words come out. “Best friend. Really.”

I'm drunk in this scene, and I took some other stuff using a trick I learned from some 8th grade acquaintances to really hammer it home. And I'm trying to tell him everything, but none of it comes out right. Neither in the right order nor with the right impact. I have hellfire conviction, but.

“Al, really. Without you, I’d be dead in a - “

“Roy,” he warns. “Don’t say it.”

Alright.

I wonder how true that statement is, anyway.

So I go on, about my various convictions, mostly to silence, trashed and rambling to myself. He’s listening, he has to be, he reacts when I say I think there’s something life changing at the end of I-64 Eastbound. Something that’ll transform me. Us, even. He’s heard it before, but maybe I say it different. Maybe I revealed enough about what I think, about these things I know to be true, real, and deeply sacred to me.

But it's not enough. It's hard to deal with it when it's just me alone in my head, seeing stars, seeing angels, seeing significances no one else seems to see. The numbers. It's harder when I tell him, and he doesn't get it.

“It’s like when your dad tells you to mow the lawn, and you think too hard about how lawns are a sign of material excess in modern America, so you get mad and you don’t do it.”

He is listening, but he probably wishes he wasn’t.

“You think about it more, and come to realize that this overgrowth of material excess is for sure a sign of a world gone deeply spiritually wrong, when there’s so much, when there’s just so much.”

I keep on, and I can’t stop.

“It keeps going, escalating until you’re convinced mowing the lawn will bring about the end times, or something equally dire. And then you try to explain at least at the surface level, that natural gardens are more friendly, to the environment, for the bees, or whatever, and your dad gets frustrated and mows it for you, over your just-sprouted sunflowers.”

This is what I think I’m saying. This is what I’m trying to say. In truth, I say something along those lines, as articulate as I could make it through a three-quarter bottle of gas station wine and more pills than I’ve bothered to count. But not quite what I wanted.

The thing about getting it is, I thought he would, which is the kicker. I thought his understanding would take away this great messianic burden I seem to have been saddled with. In this story, he doesn't get it. Here we are, two Missouri boys, two best friends who have kissed each other on the mouth, borderline lost on I-64 East, and Allen has taken to manhandling the map his damn self because he stopped trusting my judgement miles ago.

What did he expect? It’s me, after all.

“I’m pulling off this exit,” he says, shoving the map toward me, visibly upset. I take it, and I try my best to fold it up, but I’m really sauced so it’s a clumsy attempt. He continues. “There’s a motel in… Henrico? Anyway,”

And he sighs,

“We’ll spend the night, and it’s one more stretch to Virginia Beach.”

There’s a quiet solemnity to it, when he says that. I think to myself, that’s how it should feel, Al.

This is how it’s supposed to feel.

I

Fugue

It’s late May, 1997. It threatens to soon be June. We’re at the Motel 6 near Richmond on our way to Virginia Beach, Roy and I, and I just paid the late checkout fee. It’s at this point in our impromptu road trip that I find the word for what we are. How I feel. Two Missouri boys in it to win it, like it’s the Chiefs in ‘69 and he’s QB Len Dawson and I’m the guy who kissed him on the mouth in the Denny’s parking lot.

I’m still riding the adrenaline when I notice something’s wrong with him, last stretch. When he stops making sense, not that he ever made much in the first place. When he drinks himself to sleep that night, having asked a stranger at the last rest stop to buy for him.

When he stops talking.

I’m still riding the high when it comes.

II

State

When it comes, I can’t tell what it is. Roy’s always shone bright like that, like nothing can shine enough to further illuminate him, but you can’t get a good enough gander at him to figure what he’s thinking either.

When it comes, he mumbles something. Quiet, uncharacteristic. It’s not like him. He hasn’t been like himself for miles, not since the few hours of quiet mist at the Kentucky - West Virginia border. Not like at the Denny’s. He mumbles something, and it’s soft, but it flips a switch in me, and we’re passing a part of a song we’ll never play again. An open mic in Kansas City we’ll both be ashamed to admit we ever performed at. Foreboding.

And he goes. His bags stay with me. He gets like this, I guess. It’s never good when he does.

I stand there, like some kind of fucking idiot. I can’t read the room. I can’t figure him. I just stand there. He gets dozens of yards out before his words take meaning.

“Roy!” I shout. Real panic hits. So late, the sun begins to dim. Real nighttime comes.

III

Aphasia

He doesn’t hear me. I take after him, a soft trot at first, and as he approaches the intersection comes my best football tryouts sprint. He isn’t running, but he’s dozens of yards ahead of me when I finally figure it. Traffic zooms by, beaters of various generations past.

I figure it, and I’m not thinking anymore.

“Roy, hey!”

Traffic keeps zooming, and doesn’t stop. All Virginia plates. You can hear the horns in discord.

I look straight ahead, and I don’t look away, when I take him down onto the median.

And the way I tackled him, you’d think I made the team. He hits the ground clean, with impact, Virginia red clay already smeared on his denim jacket. The median is spotted with grass, rocks, broken glass. I put my full weight on top of him, but he hasn’t said anything yet.

IV

Roy

We’re heading West, and just passed the West Virginia - Virginia border. He promised not to run out into the road again, because I made him promise, so I didn’t call his dad from the courtesy phone at the Motel 6.

I was real close, though.

“Allen?” Roy asks.

I glance to my right, let it linger, and back onto the road. He’s leant on the ‘78 Firebird’s door, window open. We’re wasting gas, but it’s his car. (It’s his dad’s.) His trip. (At this point, our trip.) It’s his blond hair, getting mussed in the wind. We’re going 80 on I-64.

“Hey, Al?” he repeats.

“I hear ya, Roy. What’s up?”

“D’you remember that time? You know, the day we met.”

“Damn right I do,” I offer. “Middle school detention. You just transferred from St. Louis. Why’d you ask?”

“I don’t.”

The wind is whipping loud, so I pretend I didn’t hear him right.

“What?” I holler back.

“I said,” Roy says, “I don’t remember it.”

He cranks the window up ‘til it’s two inches open and continues:

“It feels like we’ve known each other our whole lives. Like, since we were kids.” His elaboration doesn’t clarify.

I laugh and say, “What, like we weren’t kids in middle school?”

He smiles. “You know what I mean.”

And I do.

He says, “I feel like we’ve been tangled together forever. Like both lanes here on 64, fast and slow but always connected.”

He’s one to be poetic, but only when something’s weighing on him.

A pause. I don’t have the words like he does, even now when I need them the most.

“Hey, Al?”

I keep my eyes on the road. “Yeah?”

He sighs, uncharacteristic. There’s an awareness about him that wasn’t there before. Lucidity. He takes out a dart from his front pocket, and he lights it.

After a deep drag, facing the passenger side window, he says, “Thanks."

![[The Gap Year From Hell] 1](https://us-a.tapas.io/sa/17/7b378b9b-099b-4bf0-b094-d422e828f861.jpg)

Comments (0)

See all