(In a decent, ordinary, residential nursing home in upstate New York)

A faded scene of a daily soap, fizzled on the small TV set in the resident’s room.

Wrapped in his cardigan, a comfortable old thing, frayed at the cuffs and collars, denoting its wash and threadbare spots, like the worn-out wither of old age that embodied the resident who now slumped still in his recliner.

The nurse made her rounds, and finding the resident motionless as stone and limp as a sheet, she summoned the residential physician.

The resident, suddenly wheeled into the infirmary, was placed on the table. After the typical examination and resutiatication, the physician declared the ancient resident dead.

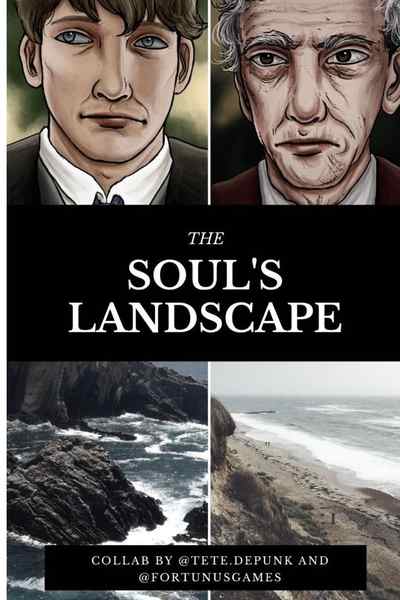

His name was Joel Farber. He hailed from the Lower East Side, and was a sharp-witted, argumentative youth of a contradicting nature of cold logic and discipline and fiery protest and obstinacy. Formerly, he was also handsome, the fine-looking type of dark haired, dark-eyed fellow that black and white photographs seemed tailored for.

(Art illustrated by FortunusGames @ tapas.io/fortunusgames)

But none of this remained, in any hint or vestige upon the wizened, splotched complexion of Mr. Farber now.

In the corner of the infirmary’s examining emergency unit, there stood, neat, trim, and compact like a shadow, a sort of specter. Dark-clad, almost indiscernible.

But Joel Farber saw him.

Being an atheist most of his life, Joel Farber never subscribed to the concept of life after death, but like many, his mind jumped on instinct and realized the spectral figure of shadow and morose spirit was… as he could conceive from concepts, none other than…

Death himself.

(Art Illustrated by FortunusGames @ tapas.io/fortunusgames)

*********

When his predecessor passed the mantle of Death’s role, when he became the Grim Reaper, if you will, Kai Haldersen, a taciturn, homely Norwegian merchant captain, had been a weary man, jaded and hard to the core, at age 36, in 1826.

He died, thus, earning his right, and in his predecessor’s view, his qualification, to become Death, in the time of Romantics.

But Kai Haldersen was the opposite of a Romantic.

He was a stone-hard existentialist. He remained unchanged in terms of form and appearance since 1826. The ever-changing nature of fashion riled the ascetic Haldersen, and liking his somber outfit from his time, he remained obstinately unchanged, though all was black, with only an accent of charcoal and silver here and there.

He disliked loud colors, and he scowled slightly upon seeing the god-awful yellow sweater with green diagonal stripes his new charge wore. And the plaid flannel pants.

But he disliked most of all, the puckered glower Mr. Farber riveted upon him as their gaze met, as the latter ascended from his now deceased vessel and manifested, as many would call it, a spirit.

The room expanded, went dark, and then the infirmary, with its machinery and blinking lights, and its tacky turquoise walls lined with red and beige border trim, became a rolling, barren landscape of a bare-treed knoll and stony hills that sloped lazily and haphazardly.

Back bent and neck arching forward, Mr. Farber sneered at Haldersen, revealing jagged, yellowish teeth. “Oh, and who may you be? I guess you’re here to take me away now, aren’t you? Or is this yet another dream?”

His knees wobbled, still unaccustomed to standing on his own.

An audacious one, realized Haldersen. Any favorable introduction that this Death held for his new charge instantly extinguished by the old man’s acidic tone.

Death would not be swayed; he could be equally maligned in his demeanor- even more than this rancorous coot before him.

Lifting his head slowly in a deliberate motion that straddled between menacing and silently authoritative, Haldersen rose his steely gaze from his downcast, hooded eyes (which rendered his piercing grey eyes all the more terrible and sharp, like a scalpel) upon Mr. Farber’s bleary, cataract-clouded set.

“And who do you think I am, Mr. Farber? Where do you think we are going?” Haldersen finally spoke.

Mr. Farber laughed, a cold, quiet guffaw. “I don’t know. I guess nowhere. I guess this is the final dream I’ll have before I fade into nothingness. That’s what I believe in, after all.”

Taking several steps with deliberate, crisp measure, Haldersen tilted his head slightly as he neared the ancient soul.

“Ah, Mr. Farber, it seems your calculations are a bit late. You have already, as you said,” and mimicking the old man’s tone and accent with a certain, masked mockery, “-FAYDEHD”(‘faded’).

Haldersen sought to declare his usual spiel of salutation, solace and explanation, as he did with the countless gamut of souls he served as their psychopomp. But he questioned now, given that damnable scowl of his new charge, if he should mete his guest with a barbed welcome instead.

He waited for the old man’s answer.

Mr. Farber shrugged. “Am I supposed to be surprised by this? Alive, dead - who cares? Either way, it’s all meaningless. What’s next? Will I get grilled like a chicken?”

His bleary eyes glared defiantly into Haldersen’s icy cold ones. “Come to think of it, that sounds rather pleasant, doesn’t it? I’d love to see what Hell’s all about. I guess you’re taking me there, aren’t you?”

He paused, and continued, seemingly invigorated by his masochistic spiel.

“Or...are you taking me to Limbo? Or something like that? As a youth, I remember people telling me that Hell as the Christians know it is just a Hellenistic invention. Before the Greek influence, Hell was nothing. It was just a holding place...for what, I don’t know exactly. But it wasn’t like how Christians interpreted it. Just cold, black, and empty. The way I like things to be, I suppose.”

Haldersen allowed the old man his rambling speculation, bored, yet amused, as time and again, with charges as onerous as Mr. Farber proved, in their initial brazenness.

There was a certain assurance in the old man’s confidence. A confidence that Death, eager like a beast to sink his teeth into prey’s sinews, anticipated to prick and shatter like a bubble.

“Ah, you are of the Abrahamic persuasion, then, Mr. Farber? I surmised as much. Most of my guests are of the same school of thought. They seek some semblance of consolation in this idea of a solid place, or solid nothingness.” Death offered the limp-kneed old man a cane he materialized from nothingness. He continued once he satisfied the old man would not teeter over like a top-heavy pile of rags.

“True, what you said is true. But if Hell is, as we know, a Hellenistic invention, what does that make Heaven, sir?”

Mr. Farber snorted. “A fool’s dream. I guess every culture and religion has some concept of Heaven. It’s great escapism for the masses, I suppose. They never wanted to face the fact that their lives, choices, and everything might’ve been meaningless from the start. So they’ve made up this idea that we ‘deserve’ things and that we will be ‘rewarded’ for doing certain things. A smart thing to do two thousand years ago, but really, quite useless now in the 20th century, don’t you agree?”

Nodding his head, Haldersen bade his time, executing the subtle pauses and waits before he spoke.

“As Kierkegaard said, this whole essence of nothingness, that nothing changes because existence is a fatalistic procession itself, is the essence of philosophy. And that makes the idea of Heaven and Hell, a theoretical philosophy, does it not? It’s not a reality you can touch or stand upon, is it, Mr. Farber?” Haldersen, his grey eyes resting with a certain, cool confidence of actually earning this man’s trust, only to bat the man back once he saw a crack to fissure within the old one’s assurance.

“Still, it makes you wonder what I am? If there’s no heaven or hell, that is fine. But does that make me the Devil, I wonder? Your thoughts, Mr. Farber. Look carefully at me, and then at this place and draw your own conclusions…” Haldersen’s quiet, soft yet rounded voice trailed off as his terribly thin yet nicely shaped lips curved into something of a smirk that looks frightening on so stern a countenance.

Mr. Farber laughs drily. “Maybe it doesn’t matter who you are. The Devil doesn’t exist - he’s just a fable. So of course you wouldn’t be the Devil. You’re just a man - I suppose, a man who has taken over the ‘concept’ of the Devil. Someone who decided to take on the role himself because it’s a chaotic world out there, isn’t it?” The wizened old man paused, licking his dry, chapped lips.

“So what is your name?” The fossil queried, raising his eyebrows slightly. “You’ve got to have one. You were alive once too, weren’t you?”

Taking a step back, Mr. Haldersen feigned a sense of remorse, actually piqued by Mr. Farber’s resiliently dauntless attitude. It stirred an equal mix of frustration and admiration, like a master bested by a newcomer.

“The Devil is a fable, and so is his counterpart. I learned this the hard way, Mr. Farber. And yes, how considerate of you to ask about my name- you can call me Mr. Haldersen- my first name is Kai, but it must sound funnier than my family name, so call me by my family name. It’s the only thing I’ve left of them, you see.”

“I see. So I was right. The Devil and his counterpart are mere fiction. So what do we have here? Just nothingness?” Mr. Farber’s eyes fluttered shut as he tried to recall something before continuing. “So Kai, as in Caius? A Roman name? I reckon you’re not from the United States as I am.”

Twice, Mr. Haldersen blinked. He continued, “You’re perceptive, I must give you that, sir. But surely you don’t think I am Roman, do you?”

Mr. Farber shook his head. “No, I’m guessing some Germanic country from the Old World. I sense a Germanic undertone to your taciturn, strict nature and the soft lilt in your words. I would know, having grown up speaking a Germanic language at home that was not English - although, it is probably quite different from your branch.” The old man shifted his feet uncomfortably, feeling exhausted already. Nevertheless, he felt a bit better than before - it seemed as if sharing knowledge had brightened his outlook.

Mr. Haldersen brightened up a mite, impressed with the accuracy of Mr. Farber’s guess.

“You’re not entirely off,” began the Death figure, his demeanor softening a hair’s breadth. “You can say I’m one of the North’s coldest sons, you see.” But now Mr. Haldersen blinked again, as if remembering an urgent duty, which he did.

But he waited, not sure where to proceed next with his charge.

“But you said your mother tongue was from the same branch as mine, no? So what was your tongue before the English malady took over you?” he asked, growing softer as he noted Mr. Farber’s face likewise ameliorated.

“It was, and perhaps still is, the Jewish language of Eastern Europe, Yiddish, otherwise known as Yidish-Taytsh, or Jewish German.” He sighs, thinking about the heyday of Yiddish theater and how one of his childhood friends, Sam Abramov, had become a famous film director, making movies in English and in Yiddish (as well as in Yinglish, the fun mix of Yiddish and English spoken by so many second-generation American Jews on the Lower East Side).

“But that’s all gone now. I haven’t spoken it in years. That’s what living in America does to you. Not that I’ve lived anywhere else, but I mean, I guess I’ve just chosen to quietly assimilate because it’s easier.” The man took a deep breath, thinking about how long it had been since he had been young and vibrant.

Whenever he thought of Yiddish, these memories of the past always came flooding back into his mind - the smell of Uncle Harvey’s pastrami (Sam’s favorite food), the cheesy grins Sam always used to spout, and something that...well, he stopped himself. No, he mouthed, stop it. Don’t think about the past anymore.

Pausing with a thoughtfulness, Mr. Haldersen carefully leaned an inch forward, as though shortening his stance an inch or two, out of a gentle deference to a now seemingly wistful Mr. Farber.

“I am sorry if you grieve the loss of your happiness you’ve left behind in youth. Did old age betray you, then?” He looked thoughtfully, as though searching for the man’s answers through the man’s questions.

“It does to many.” He pressed on.

“But it’s better to age like a mortal, than to gain that irredeemable privilege of aging without the sweet decline of old age.”

Turning his gaze above Mr. Farber, Death noted that the time drew nearer for their embarkment.

“Ah, Mr. Farber!” He tsked crisply.

“You must pardon me, I’ve been a deplorable host. First, I keep you guessing who I am (and still you will for some time, I am afraid, for a name means little for the likes of what I am, not who), and then I forget to make certain you don’t miss your boat. Please forgive me. I fear time has made my manners rust and corrode.”

Offering his arm as a second support, in conjunction with the cane the old man now hobbled on, Mr. Haldersen guided Mr. Farber down a slow by winding path to a quay where the ebb of a river remained still like flawless glass.

Mr. Farber raised his eyebrows slightly. “So this world is truly Grecian, isn’t it? I wonder why. What’s on the other side?”

Bending forward, the Death figure holds out his hand, as he boards the inside of the boat.

“Not Grecian, nor anything else of a label, be it a time or a place, or even a people. But I confess, the Greeks were right about a few things of this odd little realm.” Mr. Haldersen waved his fingers in a unified fold, indicating a requirement from his potential passenger.

“It’s proper that a ferryman should receive his due. I appreciate that some from a certain, very green island, take care to give their people at least a pair of coins for the fare. You must have something for the fare, Mr. Farber?” Mr. Haldersen asked.

The old man rummaged in his pocket and produced a small round object. Upon closer inspection, it was a pearl - a yellowish pearl that was rapidly “deteriorating,” for the lack of a better term. If you looked closely, you could see a sandy, rock-like texture on certain spots of the pearl.

Mincingly, Mr. Farber handed the pearl over to Mr. Haldersen.

“There you go. That’s all I have with me, unfortunately. I hope it’s alright.”

Scrutinizing the questionable payment handed into his palm, Mr. Haldersen, in a deft gesture, nimbly balanced the brittle pearl between his finger and thumb, eying the tiny, yellowing bead-like object with a puzzled yet expectant look.

“Such a mediocre fare, Mr. Farber! They’ve told me that in such situations, a person’s fare says much of their own selves. The way they lived their lives, you see. I wonder… what does this pitiful, decaying pearl tell me about you?” He paused, waiting for an answer.

Comments (12)

See all