It all died out with a patchwork of chaotic assaults and offensives.

What else could we do? We were picked off, like hunted animals against a hunting party. So we fought, hoping a bullet might oblige us and find its resting place in our heads or hearts.

My attachment and I had no such luck.

We dwindled down to 7 from 27, 27 from 37.

From 7 to 3.

All I had left were two privates. (Hell, I made them “privates” since all my men either deserted for the Reds, ran off to the steppe, or died from whatever godforsaken disease we all caught. I lost many to the Reds’ bullets, too.)

They were too young. Too young to have their eyes looking so old.

*****

It was March of ‘19. I remember the day- the 15th. Nothing of note for the history-makers, but it was the day of my funeral, if you will.

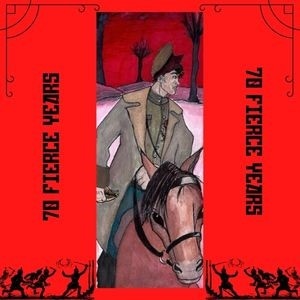

Winter clenched its fist on the steppe. Even the surface of the Father Don remained sleek with a film of grey, dirty ice. The snow laid in thick piles, like wool piles on shearing day.

Going out of Novocherkassk, we still had one train route under our control. The Reds seized most routes, though. I sensed this route, too, would be seized, so I made use of time and fled with my two privates in the dead of night when the train departed.

We had no horses. After our last skirmish, we fled on foot to hide in the brush undergrowth- our horses were seized, but we escaped.“Hey, you two.” I found my voice and tried to rouse my two privates from their numbingly silent reverie. I knew what went through their minds. They were too young to have that in their minds, and I’d be damned if I’d let that sink in.

“We’ll get you two fresh horses once we stop in Shatky.”

Distraction is the best weapon against the poison of the mind, I found.

They looked up from their blank-eyed reverie and cast their eyes on me, confused by the sudden warm comment I made, I think.

“Yes, Esaul.” came Podlipov.

A solemn, too slow nod was Kamikov’s answer.

The strange in-between time when night hasn’t quite left dawn lit the horizon as the train rattled down the frost-crusted tracks.

Our car, an empty, cold thing, rattled like a tin box.

I continued. I hoped to lull the lads into distraction, for they were too far too alert for what I had planned for them.

Occupying my hands (and bidding my time), I hunched down on my haunches, intent over the weak flicker of a little fire we made in a battered milkcan in the center of the otherwise empty car.

Taking out some paper scraps of last week’s paper (we still had something of a paper, I think, in the city), I then fumbled inside my greatcoat, and found my tobacco-tin inside that one pocket with a missing button.

“Might as well grab a last smoke before we head back into fray- well, come here, don’t stand there, you two! It’s my last bit,”

They looked at each other, and then at me uncertainly. I waved my hand, motioning them over.

“I’ve got enough for three.” I chided them, faking a tired exasperation like an impatient elder with two defiant boys. I tried to rouse something from them, a smirk, maybe.

No such luck. Maybe the tobacco would ease them, coax at least a stretch of the lips.

“Are you sure-” began Kamikov, seemingly peeved at my gesture due to his own iron-hard pride.

“Yes, now get here if you want yours, Kamikovlchik!” I growled, not so much mad, but teasing the proud lad, turning his surname into a moniker.

Podlipov, on the other hand, hobbled, dragging his limp leg with him. Resulting from our miserable skirmish, some smart Red shooter’s bullet decided to break Podlipov’s ankle.

“How’s the ankle holding up, you stubborn crow?” I asked the lad.

A grimace twisted his youthful (what was left of his already-robbed youth) features. “It’s mending, Esaul.”

His face told me otherwise.

“Now, don’t be proud.” I chided, motioning him closer to me. “I’ll decide- let me look at it.”

With a grunt and a clumsy shuffle, he obliged my inspection. Carefully, I unwrapped the thickly wound dressing and looked over the open wound.

It hadn’t healed. Instead, it grew darker and thicker- a sign of infection would settle in. A darkening streak wound around his lower calf, a sad purple and blue, showing the veins.

If he didn’t receive treatment, he might as well lose his foot- or his leg.

There wouldn’t be a field hospital at our next stop. Or if there was, there’d be no supplies. Cut off from our suppliers, our side had nothing to keep going.

Maybe if he reached his home, or hell, any home for that matter, there might be some country surgeon who could salvage it.

But I knew well he was on the way to lose it.

Still, better to lose a limb than a life, right?

How did Christ put it? Better to enter Heaven without a hand or an eye than to enter Hell intact. So I reasoned, better for this lad to live on, with one leg, than to get mowed by the Reds’ bullets or bayonets with his whole, yet broken body.

All through my poor examination, Kamikov held Podlipov tight to his side. Those two had, over the weeks in my command, become tight as magnets stuck together.

Since Podlipov’s injury after our last skirmish, Kamikov watched over him like a hawk over its young. They were both the same age- barely 19, though different in every way.

Podlipov began as a chatty jackdaw, brimming with naive idealism and all grins of pride. He confessed he wanted to return home with medals and make his people proud. He had hair the color of bread, and his hair was extra curly, which made his cap tilt all the more. Though like most of us, the recent months took out everything from us- even the curl from our hair.

Kamikov was every inch his father- a quiet Stoic wrought of steel and polished manners. He spoke French well like his father, with that Parisienne lilt most officers flaunt, especially with the ladies.

His father, hailed from further down the Don, our Kalmyk brethren. Kamikov had no curls to lose, but he wanted to grow a fine mustache, as his father had. After singeing his lip on a few sparks from his magazine, Kamikov angrily shaved off his accomplishment.

Podlipov, I recall, laughed at Kamikov’s haste, which made the latter all the more resentful. However, the two grew close, for they were my last remaining men. (And it helped, too, that Podlipov shared his flask of the good stuff with Kamikov, which reconciled the two together.)

“It’ll mend-” I lied to Podlipov now. He looked at me with a wide-eyed expectation, like an anxious patient awaiting the doctor’s diagnosis. I was no such thing, but he needed assurance. No point in shattering the lad now. “But you probably won’t be of much use to me once we reach Shatky. I’ll put you on medical furlough. Try to find me once you’re put back together, Podlipovchik!” I ordered.

His eyes widened, not in anxiety, but now in indignation, as youths do.

“Esaul! I promise I won’t drag you down- keep me on! They’ll send me back home! I promise my folks I wouldn’t get back till we set everything up and chased out the Reds!” He protested, almost shooting up like a roman candle from Kamikov’s hold.

“You’ll do me more service back home-you and your folks fend off those bastards sneaking in! You’ll keep us back if you stay!” I growled in retort, like an elder wolf reproaching the younger ones for their upstart defiance.

“And you-” I looked up over to Kamikov, who looked at me as though expecting my next order, “You better keep watch on him, make sure to put him back on the transport home.”

I returned to Podlipov, and we exchanged glares. “He’ll sneak off and try to rejoin us, I know him.”

“You son of a-” began Podlipov. I cut him down.

“You want a martial reprimand on your record?”

He shook his head, flattened by my threat. He desired prestige too much to risk it.

“Then button your lip, private!” I finished.

I assured them.

“ Ah, you two, it’s a mess, all right. We’ve got to pull through it, though. The Reds’ll tire us of soon. If we don’t get to them, I’m damned certain this winter will.”

“If it doesn’t get to us, first.” Kamikov commented, blowing on his blue hands to warm them vainly.

“We’re stronger stuff than them- they have it too good, but we’re used to this shit, aren’t we?” I huffed. I felt an anger towards the superiors, but I couldn’t voice my doubts fully to my subordinates.

They needed trust in the command. It’s harder when you’re part of the command, though. You see right through it all, and you yourself know too damn well you’re part of the blind leading the blind.

Dawn now began. The darkness turned into that harsh blue that soaks up everything. The snow helped to light it up even more brightly, and we could make out the outline of a town in the distant. It wasn’t Shatky, but here was good as any to put my plan into action.

Still, I waited for that lull to strike.

Rising up from my position, I stepped over the edge, leaning against the half-open box door, holding onto the jambs as I rocked with the sway and shake of the car on the tracks.

I stared for a bit. My privates fell into a blank-eyed stupor, staring out flatly against the white and dirt grey of the land rolling before us.

Now was the time.

I leaned further out, pretending to see something in the distance. I shieled my hand over my eyes, as though peering for something.

They noticed and perked up.

“What it is, Esaul?”

“Is it them?”

“Well! I’ll be damned. You won’t believe it…” I finally said, still staring out intently, or so I pretended.

“What is it?”

“A stag! A white stag- it’s running across that knoll there-” I pointed at a snow-covered knoll. There was no stag, but I needed to get them into position.

“Don’t let your eyes deceive you- we haven’t seen any deer in ages, Esaul!” Kamikov doubted.

“Well, it’s a sign from God, since there’s one there now! Come and look at it!” I urged them.

“I think you’re crazy with no sleep, Esaul!” Podlipov grumbled.

“You two keep yammering, you’ll miss it! Now get over here and see it! Look!” I kept urging them to the edge.

They groaned and complied.

“Where the hell is it-” Then Podlipov remembered respect, and added, “Esaul?”

“Right there- hell, get closer, will you two? Look, right there!”

“You mean like on the flag?”

“Yes, like on the flag, stick your head out, you’ll see it better-I’ll get out of the way! Get over, before it disappears!” I moved out of the way, and shoved my privates right on the edge of the car.

“Where is it, I don’t see it…”

“A white stag- how can we see it with all this damn sn-”

I struck.

Taking a few paces back, I readied myself quickly, and like a bolt of lightning, I rammed my shoulders against them as they leaned out over the edge. I shoved them off. They dove, tumbling out the car onto the mounds of snow that lined up right with the track-side.

“Don’t try to follow, you son of bitches!” I hollered back as the train kept its speed.

“You ****!” screamed Podlipov, scrambling from his face planted in the snow.

Kamikov jerked up beside him, and he hollered something in the Kalmyk words I guessed was the same as Podlipov’s curse.

Comments (13)

See all