“You’re going to be successful and make us proud.”

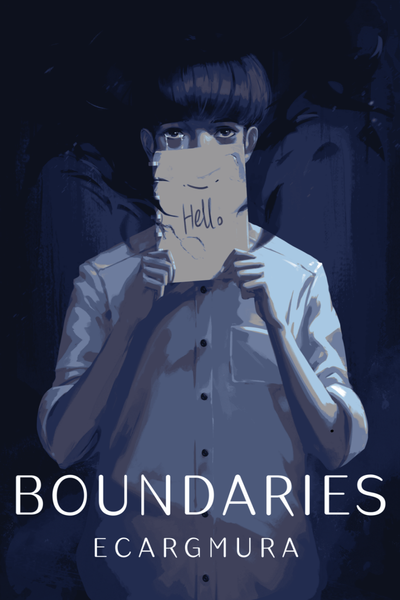

Those are words that have been drilled into my head since I was old enough to think for myself. As the son of South Korean immigrants, I grew up in an Asian household where my family nurtured me in Korean customs. However, I was born in America, meaning that I was also nurtured by American society. That is what being Korean-American is like; I am not bi-racial—I’m just an Asian man that was born and raised in another country and living in an amalgamation of customs from the inside and outside.

My parents had high expectations for me growing up. Not only was it because I was the son in my family, but it was also because they wanted both Eura and me to live our lives to the fullest. The way they did it wasn’t the ideal way, however. To me, their idea of perfectionism was warped. They wanted me to participate in so many things in order to become successful. They made me do everything like taekwondo, piano, art, and the sort—anything to be the source of bragging. I wasn’t good at taekwondo or piano growing up, but I was fond of art.

My passion for the arts grew whenever my art teacher at school praised my drawing skills; I do admit that I did draw better than my peers growing up. I always felt happy whenever I drew something. My parents did not really think that art was the ideal career, however. They wanted me to be an engineer or a doctor—anything that can make a lot of money.

If I had to describe my childhood, I would compare myself to a machine. Growing up, I learned that studying wasn’t really my strongest suit. I had considered myself more of a daydreamer than a realist. I couldn’t balance school and hobbies together, which was something my parents didn’t like. They would always try to force me to study when I didn’t want to; their attempts to make me study ranged from taking away my sketchbooks and coloring materials to focus on school work to forcing me to go to after school tutoring to focus on my weakest subjects. Forcing me to grow up in an environment where my free will was subjugated did little to help me grow.

I remembered dreading days where report cards were handed out. I didn’t mind them until middle school where my grades started dwindling the more distracted I got. The sight of my parents looking at my grades and incurring their wrath was like venturing into the sun and finding its core. The lowest grade I’ve ever gotten was a D. In Asian family standards, a ‘D’ meant I was on thin ice; if I had gotten an ‘F’ on any subject, I would be living on the streets.

As a teenager, I grew up learning that every bad grade I had gotten meant the countdown to my destruction. I remembered the angered faces, the eyes full of contempt, and the demeanor that had disappointment written all over it. It pressured me because it made me feel inadequate, like I had to try harder just to appease my parents and not for myself. There was one instance that I remember where my mom had said, “If you keep making bad grades like this, then I shouldn’t have had you.” Her words had stung.

Being deemed a failure by my parents was a feeling that felt worse than death. In order to make them happy, I put aside my dreams of making art and studied hard in high school in order to go to a prestigious university. I eventually accomplished that.

College life was decent, but it was missing something. I remembered doodling a dog during one of my classes and realized that what was missing in my life was art. I had missed drawing and making pictures so much. The listless life I had lived regained its color when I started drawing again. Behind my parents’ backs, I started going on social media to post my very first original artwork—a serene work filled with colors which I had titled ‘Colors’. It didn’t get much attention, but I was happy with the start of my life as the Internet artist Quackgene. After this, I drew some fan art for popular media and got some attention.

However, the more I draw, the more I realize that I cannot live a balanced life; this was the reason why I refused to take art classes in school. If I focus on one thing, then the time I focus on another thing dwindles. The more I draw, the less school work I get done. Even though I should have stopped, I couldn’t put my pen down. I just wanted to draw.

The consequences came to me as my grades dropped the more I got distracted. My parents got note of this so they reprimanded me. As someone who was majoring in something I wasn’t passionate about, I had rebelled for the first time.

“Umma*, Appa**, I’m not interested in engineering. I want to be an artist.”

When I had told them this, they had given me a confused expression and asked, “When were you interested in art?”

Hearing that question slightly wounded me. They were the ones that praised my childish drawings when I was a kid and yet they didn’t think I have a passion for it until I gave it up to please them.

That was when Eura stepped in and defended me. “How can you say such a thing to him? He always liked art. You didn’t care about it because all of your friends had kids that excelled in studying. All you wanted was for him to be good at studying. You were like this with me too! I told you I wanted to be a musician, but since their success isn’t guaranteed, you told me to not become one and pressured me to stop music.”

When I learned about this, I felt bad for Eura. I always remembered how much she loved playing piano. It was something she was forced to learn but grew to love. I had never thought that she wanted to be a pianist.

“And you’re happier now, right? You’re studying law and want to become an attorney. You’re going to be successful and make us proud.” Dad remarked.

“I had to find another dream because you two don’t support it! How can you decide if I am happy or not when you’re not me?”

Mom quipped, “I gave birth to you. I raised you. I know everything about you, so I decide what makes you happy or not. Part of my blood is within you after all.”

I saw Eura having a very hurt expression. Hearing those words had wounded my heart as much as it did hers. I felt hurt and trapped. It felt like I was trapped in an encased glass maze, unable to find an exit. Instead of wanting to escape, I just let myself become accustomed to these barriers. It’s a reminder that I am a human who cannot achieve his own happiness until his own parents are happy. Parents must always come first. I cannot prioritize myself—ever. It was like a brainwashing spell in order to assuage the guilt of wanting to have my own agency.

Eura did not want any of that, however. “Mom, I am a human with free will. Saying that my happiness is decided by you only means you see your kids as machines. I cannot accept that.”

“Then leave.” Dad looked at Eura in a frustrated way. “Leave and don’t come back.” In Asian households, when a parent tells you to leave, they don’t mean to actually leave; it’s more of a threat. They do not disown you, but the relationship between parent and child does sour.

Eura was someone who would take words in their literal meaning, however. “Fine, I’ll leave! Let’s go, Eugene.” She stormed off while dragging me away. She was someone who held grudges. If she got angry, she wouldn’t talk to the source of her anger until they apologized. She’s also very stubborn on top of that. She’s someone who will always get her way, no matter what. I had always admired that about her; she was much different from the reserved me who only cowers in fear and lowers my head for those above me.

After that event, Eura did her best to encourage me to become more confident, but I still couldn’t take her advice to this day. The more I want to be confident, the more I cower. She even suggested that I live alone, away from our parents to help me become stronger, but I’m still weak.

In order to mimic her confidence, I avoided my parents no matter how many times they contacted me. I had convinced myself that I hated them for ruining me. The last time I had seen them was during my college graduation where we had not spoken to each other. I did appreciate them coming, however.

I always tried to convince myself that I hated my parents and that they were the cause of my deterioration, but deep down, they weren’t at fault. I know they were just looking out for me in their own way, even if it wasn’t the best way.

I do not hate my parents, but after the incident, I found it awkward to be around them. I do not know if they have changed over the years or if their mindset is still the same. All I can do is dread the moment I see them again.

--

Comments (0)

See all