He told his crumbling body to get up and go after her.

He had managed the getting up part, at least he had pulled himself into a crouch, by the time she came back and dragged him all the way to his feet. She let him go. He slumped against her while she jammed both hands into his pockets and felt around. There were some spare strings in the vest. She threw them down.

“Do you have anything?” she said. “Coins?”

“Coat,” he managed. “In the coat…” She left him again. He stumbled after her. The tile floor was cracked and loose and treacherous.

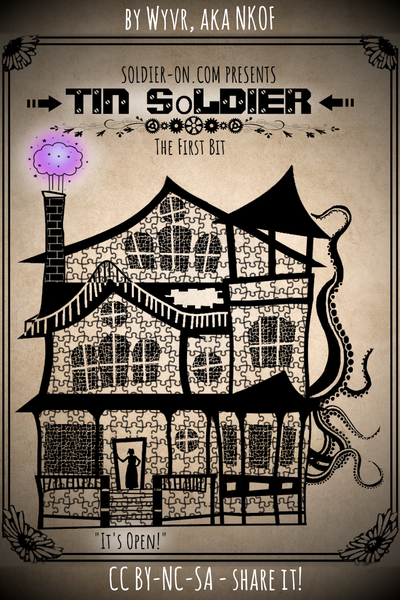

The front room was wide and bright, with a sweeping staircase. It had been intended as an atrium. The skylight had been removed in a rather spectacular fashion. The tarp closed the space above. The kitchen was behind, through an open doorway that had been cleared of both door and hinges.

Metal, what there was of it, tended to collect in the kitchen, and the large window and broad table made it fit for a surgery.

There was a hopeful clatter, then a cry. “Oh, you useless son of a bitch!” She turned to glare at him, “Tin?”

There was a ladder back chair with a raffia bottom. He collapsed into it. “Both?” he said. “Tin? Both tin?”

“Both tin!”

“I hoped… steel…”

“Don’t you know the difference?” she snapped. “Not even by now?”

He shook his head, ashamed. “All I could find.”

“Why don’t you have coins?”

“I left it,” he said. “I left everything. I ran.”

He thought of the case, open and inviting. There would have been coins. If he had gone back for the case, there would have been coins. Nickel, and copper. Strong metals. Good coins.

“I’m sorry.” He began to weep.

“Stop it,” she said. “Is there anything else?”

“Brass tack,” he said. “Chain link. Iron. Look.”

She rifled the folds of the coat and found what he had told her. She was already shaking her head. It wasn’t enough.

“I have iron,” she said. “I have most of a frying pan. But I need bone!”

“The tin…”

“Tin is soft! I can’t even make staples with tin. I’m not going to make a skull.”

“Just for right now…”

“It’s not just for right now, it’s for the rest of his life!”

She closed her eyes, trying to banish the image of it. He wouldn’t live long that way, and every moment would be such pain. To prolong life, the mere existence of life, at the expense of everything else that living was supposed to be about… That was not her purpose.

This child, practically her own child, was lying on the table, bleeding and dying, and she could save him, but not like that.

Mordecai stood suddenly, upending his chair. “Use what’s in me!”

She dismissed him, “No.”

Her thoughts were elsewhere. There were still nails in the house, in the walls, some in the roof, but it would take too long to gather them all, and it might not be enough. Most of them would be iron and not steel, anyway. That was why they were still in the house, and there they were liable to remain.

“There isn’t anything else and it has to be right now! Use what’s in me!”

She stopped taking inventory just long enough to remind the stupid man, “That would kill you.”

…They hadn’t replaced the doors on the pay toilets in Strawberry Square yet. The storage building across the alley might’ve replaced the locks, but what would she do if she took the time to look and they hadn’t? The General might’ve been holding back some medals, but that was the same problem — time lost for uncertain results.

Erik might slip away if she left him and ran upstairs just to explain. Mordecai certainly couldn’t…

He snatched her and shook her. “I don’t care!”

“I know you don’t care,” she said. “That’s why I’m the one telling you no. I don’t kill people.”

“You’re killing him now!”

She shoved him away with a snarl, “And you’re helping to kill him! I am trying to think!”

He staggered back from her and sat down on the floor. She ignored him.

Tin. What can I make with tin? I have iron, but that doesn’t go. Lead goes with tin, but that’s poison. Copper goes with tin, but I haven’t…

She tweezed the tack between two fingers and held it before her eyes.

I have brass. I have a little bit of copper. I can pull it apart.

A little bit of copper was enough for an alloy, but not by itself.

Oh, please, tell me I still have some. I think I still have some.

“Mordecai, get me my bag.”

“What?” said the man.

“Get me my doctor bag, you weird, stupid man! It’s big! It’s black! It’s on the counter! Get it!”

She stripped off both gloves, pulled down her goggles and began to mould the brass tack in her bare hands. It glowed a dull red that rapidly brightened.

She felt more than saw the make of the metal. She understood it. Separating the parts of an alloy was sometimes simple, like slipping a single strand out of a braid, and sometimes more difficult, like pulling apart two books whose pages had been interlaced. You couldn’t just yank them apart, they had to be undone.

Brass was not quite so complicated, and there was so little of it. After a brief, bright flash, the filament of copper between her fingers was already dim and cooling when the dark leather bag thudded down on the table beside her.

Mordecai was panting. He sounded like an ancient bellows. She was going to have to mend him too. That would require gold. But that would be later.

She laid the copper thread on the dark fabric of the coat, where its shine would be easily seen, then she delved into the bag with both hands. There were medicines in here. Sulfa. Morphine. Iodine. Tablets and powders and syrups. But there were also metals, fine powders corked in bottles, too delicate or rare to be used on their own. Most were silver, of various textures and shine.

A paper label showed her scrawled block letters in black ink that was fading purple: ANTIMONY. There was nearly an ounce of it.

“That’s poison,” said Mordecai. The bottle was ridged, so you would know it by feel.

“It’s just not good to breathe it,” said Hyacinth.

This was mostly true. But a little bit of poison would be better tolerated than a broken skull, even for the rest of his life. “I want you away from here. Go back where you were.”

He stumbled, but he successfully navigated the distance. He couldn’t pick up the chair. He sat down beside it. The floor was cold. “You’ll fix him?” he said.

“I’m fixing him,” she replied. “Don’t look at the light.” She heard him weeping.

It didn’t matter.

There was no need to disinfect, not the wound nor her hands nor the surface. The heat of the process would kill anything bad. She did pull down the coat, so that the sparks wouldn’t catch it on fire. She yanked open the boy’s shirt, scattering the buttons, and pulled that down as well.

His body was dented with red marks that were bruising. There was a sharp divot in his side that was surely the broken rib she had felt in him. He shifted and moaned. She winced. She had hoped he wasn’t conscious enough to feel those things for himself.

“Erik, if you can hear me, I’m not going to hurt you. It’s going to smell funny and it’s going to feel hot, but that’s all. I’m going to cover your… your eye.” There wasn’t much left of the other one to protect. “Don’t open your eye.”

She secured a gauze pad with a strip of tape, then dampened it with a spray of water from a bottle. “Okay. It’s going to be okay.”

Mordecai drew his knees to his chest and buried his head in his arms, hiding like a child.

The light was bad, the particular quality of light that resulted from the merger of body and other, but the smell was the worst. Hot metal and burning flesh, and burning bone. He never got used to the smell.

Memories rose of twisted bodies and screaming mouths. The medics rushing down the aisles of the infirmary with dark bags, patching gaping holes and replacing lost parts with whatever material they favoured.

Metal, for some of them, like Hyacinth. Stone, for others, or plant matter. The worst of them used flesh, and they would flense the bodies of the dead and sometimes the dying to save others who might live.

Such unforgivable acts had pushed all magic-users to the fringes of society. The ones who could hide it, the learned users, did. (Barring certain eccentrics who still practised their trade.) The innate users, who showed their proclivity in their coloured skins, could not. They were ostracized, marginalized, forbidden housing and employment.

Given half a chance, they would be beaten.

They were kicking him.

He curled up tighter and tried to hide from the thought.

They weren’t trying to help him. He was hurt and they were kicking him.

And they were laughing.

He had done something to them. He didn’t know what. His own ability was hardwired but (he had thought) weak and harmless. Something had come out of him that was loud and bright. It had made them go away from the child and he hoped it had hurt a lot.

He hoped, also, that it wouldn’t follow him back here, but that was much less likely. Whatever it had been, it wasn’t subtle, and the crowds would have seen a red magic-user running away from it. It was not unknown that magic-users lived in the broken-down house on Violena Street, all kinds.

Comments (0)

See all