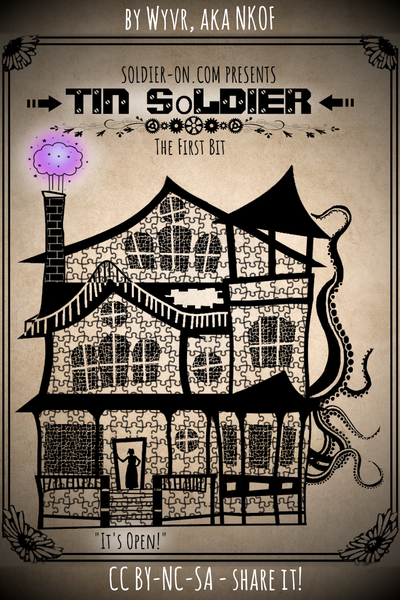

Illustration: The General’s tarot card, The General, based on The Chariot. She appears at the upstairs railing in her nightgown, annoyed.

[PSI-3]

At the first opportunity, she could not go in and see to Mordecai. There were more coming and she needed things for the people she already had. Ann was in the basement, Barnaby was charting things and gluing them to the kitchen wall with soft-stick charms, and the General was (hopefully very deeply) asleep.

There were no locks in the place, fortunately, and no doorknobs beneath which to brace a chair. The General’s room was therefore accessible at all hours, whether she wanted that or not. Now, she was perfectly capable of repelling any unwelcome visitors, but only when she was awake.

Unfortunately, her military experience and training had rendered her level of consciousness more of an act of will than a physical condition. If she sensed something was worth her attention — possibly with some kind of metaphysical alarm system, Hyacinth wasn’t sure — she could attain full focus and understanding in an instant. She had probably already been up, detected yet another riot, and gone back to sleep.

Hyacinth crawled in, using only the slit of light from the cracked door for navigation. There were two chairs in here, and a desk and a bookshelf. One double bed rested on wobbly legs and one single on the floor. She gave the double a wide berth and approached the single on hands and knees.

“Maggie.”

“Huh?”

“Shh!” She clapped a hand over the child’s mouth.“Don’t wake your mother. Come out with me.”

They both crawled.

Hyacinth eased the door shut again with a tender, terrified touch. For a moment, they waited for sounds from within. When avian death did not overtake them, they stood and walked a short distance to the stairs. Maggie was in her nightdress, a white cotton thing. The tarp on the roof let in the night air and she was already shivering. Fortunately, her day clothes were in the hall wardrobe, not in the room.

“What happened to your hand, Miss Hyacinth?” the girl said.

“It’s for Mordecai,” said Hyacinth, showing the palm. “Maggie, I have to have metal. Will you take Ann’s shopping basket and go out looking for me? Some of them are bringing it, but it’s not enough.”

She pointed over the railing, into the atrium, where a small crowd was gathering. Some of them were waiting for their friends or family in the kitchen. Some of them were waiting with friends and family to get into the kitchen.

“Should I steal things?” Maggie asked her.

Hyacinth was already nodding. “Yes. Steel is excellent.” She stopped and turned abruptly. “Wait. No. What did you say? You steal things?”

Technically, going through other people’s trash was stealing things, but so many people did it that it hardly counted. Maggie must mean actual stealing. Like houses and pockets.

“Yeah.” She rubbed her eye with a hand, a nine-year-old girl with braids and a white nightie.

And a mother who could take your eyes out before you could blink.

“Do you know how?” said Hyacinth.

“Soup taught me a little.”

“Soup did?” Hyacinth thought any child that consistently hungry could not be an accomplished thief. “I don’t know, Maggie. Can you show me?” She took off her goggles, “Can you steal these?”

“No, because you know I’m gonna.”

“Fair,” said Hyacinth. “Okay, get dressed first. Then come downstairs and we’ll try it there.”

———

Maggie delivered her two pocket watches, a folding knife, and a wallet, all without noises of surprise or offence.

Hyacinth held up the wallet and scolded her with it. “No wallets. There’s no metal here, just notes. Money clips, if you must.”

“You could buy metal,” Maggie said.

“Not at this hour.” Hyacinth paused, thinking about it. “Not from anyplace I’m willing to send you,” she amended. “All right, you can steal, but just from people, don’t go inside houses. Stay in crowds. Don’t steal from police. Don’t steal from prostitutes.”

“Why not prostitutes?”

“They’re canny and they wear tight clothing. And they can’t afford to lose the money.” She shook her head. “Don’t take risks, Maggie. Don’t get caught, you’re no help to me caught. And if you see good trash, grab it. Don’t just steal.”

“Yes, ma’am.” Maggie saluted, and she clicked the heels of her shoes together. She was grinning. That, and the “ma’am” proved she wasn’t nearly as serious about this as she ought to be.

Hyacinth held up a finger. “Maggie, if you get caught, I’m going to have to tell your mother it’s all my fault.”

The girl’s expression fell. “I won’t get caught, sir.”

“Thank you.” Hyacinth saluted her back. “Dismissed. Hurry. Go.”

Magnificent snickered and ran out.

Hyacinth held up the wallet and demanded of the room, “Hey, did anybody drop this?”

She pocketed the watches and the knife. She would use them soon enough.

———

When she finally did have a moment for Mordecai, she took a bottle and a jelly-glass. The glass had a strawberry with a smiling mouth and was of sufficient capacity. The bottle was of more than sufficient capacity. And she couldn’t very well forget the gold.

The red man had not attempted another escape since they had put him to bed the second time. She felt certain that if he had, she would’ve found him on the floor.

There was a strew of wadded tissues on the bed beside him, and quite a few of them were stained with blood. He always screwed them into little balls to hide that, even now. He was not coughing at the moment, but she could hear him trying to breathe even from outside the door.

“Mordecai?”

He managed a faint sound.

“You’re going to have a glass of whisky before I do anything.”

This was coercion, pure and simple. If she’d waited until after, he would’ve said no. Now, he just nodded.

She poured until the strawberry was just touching the surface of the liquid. Mordecai was teetotal — barring special occasions and truly hideous song requests — and that ought to be enough to keep him down and out of trouble until he’d had a chance to heal. A few hours. Maybe even past dawn.

And if he tried to get out before that, it would certainly kill his ability to stealth.

“All right. I’ll help you. Just like cough syrup.” She crawled into the bed beside him, drew him upright, and held the cup while he drank. He would’ve just dropped it if she let him have it because the first swallow started him coughing again.

He tried to push her away.

“Nope. All of it.”

He drank all of it.

“Now let’s see to you.” She let him back down on his pillow and she pulled up his nightshirt to his throat, exposing sensible underwear with a faded pattern of blue stripes.

A thin gold scar divided his hollow chest. It was somewhat jagged, as she had forced the metal through in the first place. That had hurt him, and she’d had to hold him down. Now it was easier. There was a path straight through. She put her hand against it and she felt what she’d done to him.

His lungs were bad. He’d had a few doses of gas during the siege, one of them quite severe. Even a little gas was enough to leave permanent damage, but it wasn’t like he could quit what he was doing or get out. It had been cold when she found him, and he’d been holed up in an abandoned hotel with no heat for almost a month, and walking around in the snow all day.

He’d thought he was dying. He was, but not that way. He required immediate repair and he had cheap gold on him, so that was what she used.

Gold was best for flesh, but not cheap gold, and the lungs required a flexibility of material that metal was never going to provide. They were stronger and they moved the air a little better, but they’d lost some expansion, and when he pushed them the bonds had a tendency to come unglued. The metal just couldn’t keep up.

She redid the merger with the gold she had in her palm. It didn’t need much, and it only took off the first layer of her skin, which anyone could afford to lose. The glow lit up his body from the inside, but wasn’t enough to require eye protection.

He gasped and sat up, snatched another tissue and coughed into it.

“Careful,” she said.

He nodded, coughed, and crumpled the tissue.

“Hurts?”

“No. Dizzy.”

“Good. Lie down.”

With a click of her tongue, she noted a scrape on his knee. He must’ve done it falling down the basement stairs. Red on red didn’t stand out; she wasn’t paying enough attention.

She had a handful of adhesive bandages in her pocket, with grey gauze pads coated in healing silver. She applied one, then drew the blanket over him. “Get some sleep. And I mean that. I can’t be in here with you. I have to trust you.”

He laughed faintly.

She nodded and got up to leave.

From under the blankets, without movement: “He’s dy-y-ying.” It was drawn out, almost sung. There was another laugh, or maybe a sob.

“No,” she said. “He’s healing. It’s going to be hard, and you need to get better so you can help him.”

“I promised her I’d take care of him.”

“You have and you will. But please go to sleep. If you don’t do it now, you’re going to be in too much pain.” She was backing towards the door. She did have to go, whether he was going to break down or not. She’d have to send in… Someone she knew vaguely who was ambulatory to check on him.

She would not send Barnaby.

“It’s dizzy,” he said.

She sighed. “Put one foot on the floor. That helps.”

He shifted and did so. “’S better.”

She said, “Goodnight,” quickly and got out of there before he could say anything else.

The front room was full of people and there was at least one infant crying. This was her element, apparently. It did seem to happen often enough.

She clapped her hands for attention and then cupped them around her mouth. “All right, damn it, let’s get this travesty organized! What’s wrong with you? Nothing? You’re helping me. And you’re helping me. Does that baby need something or is it just upset?”

———

Dawn was touching its rosy fingers against the blighted landscape visible from the kitchen window, painting everything in cold blues and faint pinks.

She had just about sorted everyone. More would undoubtedly show up during the day, but not with such urgency. The fires were burning themselves out and people had jobs to get on with. Glass would be swept up and storefronts opened. Commerce was necessary for the purchase of repairs. Capitalism, devouring itself.

The front room and the yard were completely clear as she escorted a limping man down the porch steps.

“Come back and pay me sometime,” she told him, as she told all of them. He might. Enough of them would. Negotiation of payment was impossible in a crisis, and she had to count on people’s consciences and sense of self-interest. She had no way of knowing the ones who didn’t come back, but she remembered the ones who did. That person paid me. That person gets credit if they need it.

She did a sweep of the house before heading back to the kitchen. Barnaby was snoozing in a chair in the front room, with scrawled papers scattered around him. There was a crumpled blanket on the floor, there were blankets left everywhere, and she shook it over him.

Upstairs, there were no noises from the General’s room. She had sent Maggie back to bed a couple hours ago, and hopefully that was enough sleep to get her through her lessons unscathed. Maybe she could say the noise downstairs had kept her awake (although the General probably expected her daughter to sleep through mortar fire if it was required).

Milo and Ann’s room was open and empty. A forest of silk stockings and lacy underthings hung drip-drying from a jagged arrangement of clothesline, and one grey cotton shirt.

The allocation of space in Ann and Milo’s closet was a bit unfair. Milo had two shirts. He wore the white one while the grey one was drying, and the grey one while the white one was drying. He also had two pairs of pants, but they were exactly the same, and one pair of shoes.

At the top of the basement stairs sat the radio. The Bakelite case had been battered and chipped. There was a little round hole right through the centre of the glass face, as if it had been shot. Beside it was a single marabou-edged slipper with a broken heel.

Evidently, the fact that the radio was A) not on, B) unpowered, and C) devoid of all metal parts, was not enough to satisfy Ann. Hyacinth could only hope that killing it and exiling it had calmed Erik.

She went downstairs and found Mordecai sitting beside the narrow cot with his head buried in his arms. She sighed. She had expected it.

He was dressed, at least, and he must have managed that by himself.

He looked up at her but made no attempt to rise. “He’s so hot.”

“I know,” said Hyacinth. She crouched down and touched the back of the child’s hand. She dared not touch his head. He was hot, and damp, but he was breathing and he was quiet. He flinched and curled his fingers when she touched him.

“That hurts him,” said Mordecai.

“I know,” she replied. She stood. “He just needs time.”

“Maybe we should put him in the bathtub,” said Mordecai.

She winced. “Mordecai, are you doing all right, there?”

He turned away from her, back to the child. “I am. I was just thinking of something.”

She put her hand on his shoulder and made him look up. “I know what you’re thinking of. Don’t. It isn’t like that. He’s not sick…”

“That doesn’t matter!”

“…And you’re not alone,” she finished sternly.

He nodded, sighed, and dropped his head.

“I’m just in the kitchen. If you need me, shout.” She trusted he could do that, now that she’d fixed him. “Hey, have you seen Ann?”

“Not for a while.”

“Huh. I’ll keep an eye out for her. Or either of them, I guess.”

Comments (0)

See all