Walking blind, even when being led by the arm, was not easy. I could tell they weren’t taking us down the road, which meant they weren’t complete fools, but it also meant the going was rough. I stumbled more than half the steps I took, and this Anton Pavlovich wasn’t gentle about jerking me up, so my arm always felt like it was about to be wrenched out of socket. As soon as I got the chance, I was going to rip his arm clean off.

“We’d go a lot quicker if you took that blindfold off him,” Nadya said from somewhere in front of us.

“Then he’d see all our faces and where we’re going.” Stiva.

“Only matters if he ever gets back to his family.”

Anton Pavlovich stopped, so I stopped, too. His hand left my arm for a moment, and something jerked at the back of my head. The blindfold fell off, and I blinked in the sudden brightness. When I adjusted, I saw them for the first time: Stiva, snub-nosed and scowling; Nadya, wispy hair piled messily on her head; and Misha, top of his head barely at Nadya’s hip and hand clutching at her belt.

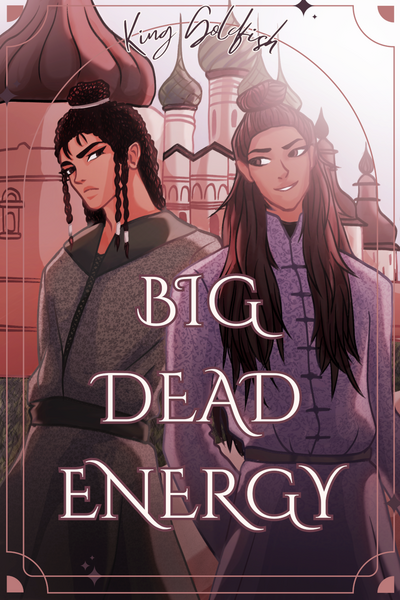

Anton Pavlovich’s hand reattached to my arm, and I looked up at him. The first thing I saw was the smirk on his face. It would be there more often than not, even when he was concentrating hard on something, like the expression was just burned into his muscles. His eyes were quick, always looking around, and sly, more gray than brown. His black hair was burnt brown on the ends by the sun, half of it grazing his shoulders and the other half tied up with a frayed bit of twine, the ends broken and sticking out in odd directions.

“Go on,” he said, quick eyes meeting mine. “Face forward, so you don’t trip.”

Anton Pavlovich was clearly the oldest among them, and he couldn’t have been much older than I was. I didn’t know what the group of them was doing in that cellar. Perhaps they were there for safekeeping, and I was an unexpected bounty that fell in their laps. Now, they had to bring me to someone who knew what to do with me.

We walked through the tall grass fields, the same as all the others I’d seen in Veliko, interrupted only by the occasional pond with one or two skinny, twisted trees growing on its banks. So dull it felt like a waste of my newly returned eyesight.

It took all my meager self-restraint, but I didn’t make a fuss. The khozyain said the first time they let their guard down, they were dead, but I had to convince them to let that guard down, first.

Around the time the sun reached its zenith, we stopped, hunkered in the valley between two little hills that housed another of those sad, brown ponds. Probably a watering hole for some now-dead cattle.

Stiva pulled some bread and pieces of fruit from a pack and handed them out. I had hoped they'd cut the ropes on my wrist to eat, but I was hoping for too much. Anton Pavlovich pulled the gag out of my mouth but said I’d better not start carrying on. He told me to open my mouth and popped bits of crust inside.

“Why should we give him anything?” Stiva complained. “He’s been living his whole life on the fat of the land while we get the gristle. Did he ever give us a crumb?”

“He’s not from here,” Anton Pavlovich said. “He’s from Khorizova.”

“Even worse,” Stiva said. “So he’s one of those sticking his nose where it doesn’t belong, enforcing for Knyaz Fadej just because they’re both rich.”

“Fuck you,” I said, swallowing dry crumbs. “I don’t want your scraps, anyway.”

“Hush now,” Anton Pavlovich said, like I was a startled horse. “You’re going to want our water.” He held a waterskin to my mouth, and I had to admit I was thirsty.

When he was done dribbling a few drops in my mouth, he drank from the skin himself, Adam’s apple bobbing in his long neck. The knife was in his hand in his lap. His grip was relaxed. Stiva and Nadya were bickering quietly as they ate, and Nadya was tearing pieces of bread off for Misha, who looked like he should have been plenty old enough to do that himself. Dasha wouldn’t have been caught dead doing something like that for me or Semchik, though it did seem like something I would do to Semchik, long after it was anything he needed or wanted done.

The point was, they were distracted, so I had to get to work. I didn’t know how quietly I could do it. Something like this needed control. I was sure Sanya could do it in his sleep.

It had been easy, had come without thought or intention when I punched that man so hard it killed him, but I had thought and intention now. Those things did not always work in my favor. I tried to turn the myortva on like a valve, just let a little trickle down into my arms. I pulled my wrists apart, but it wasn’t enough.

Okay, more.

Still not enough, but I felt the ropes begin to fray, fibers pop.

A tiny bit more, then.

The rope snapped with a loud pop and my arms flew out to my sides.

Anton Pavlovich dropped the skin and lunged at me with the knife.

I threw my hands up and pushed myortva.

Someone grabbed my hair from behind, and the blast of energy shot up over his shoulder at the same time his knife sliced up my arm, filleting me from the underside of my wrist up to my elbow.

I screamed, and the myortva shut off.

Nadya, who had me by the hair, wrapped her arm around my neck and closed her elbow on my windpipe.

Stiva yelled, “Stab him!” and I tried to shoot myortva out again, but I couldn’t focus on anything but the pain, and all that came out was a light, harmless wind.

Anton Pavlovich flipped the knife in his hand and hit me across the temple with the hilt. My vision flashed white and my body went limp, and when the world came back into focus, I saw the hilt coming at me again.

Comments (7)

See all