Lucius Vitus Servius once said that rivalry within ranks festers like flesh rot, and if a general ignores it, he’ll lose a man as quickly as a leg. Julius recalls his old friend’s observation as he watches the murdered man’s son glower at Kombius, a prince of the continental Atrebates.

The more concerning bit of flesh rot, however, is Titus Labienus, who listens with jowls tight in resentment as the noble speaks of his time as an Ancalite prisoner.

Before their first campaign on the island, Julius had sent Kombius ahead with a mixed group that included Roman emissaries. The aging Ancalite king, a man of Belgic blood, took Kombius and the emissaries prisoner, killing Labienus’s son in a spilling of Roman blood yet sparing the Atrebates.

Young Skipio and the older Titus have lost more than most, certainly more than Julius, whose aunt’s youngest son, Planus, engages too eagerly with the esteemed Kombius. The hirsute Gaul’s blond locks spark more than conversational interest, and as he regales the smitten Planus, his light eyes steal glances at Skipio’s lion-headed helmet.

“In your time among them,” when Skipio speaks, Planus aims an anxious glance at Julius. “Did you ever talk with the druid, Fintan?”

“The Owl counseled Cassibelanus to anticipate Rome,” Kombius answers. “He wanted no part of it until his wife whispered poisons in his ear that led him and his chariots to Belgica.”

“We know this woman,” says Julius. “Is she a druidess?”

“She would’ve been,” Kombius replies. “Getting pregnant made the old archdruid—”

“Ostin,” Skipio cuts in, and Kombius sets down his cup.

“Ostin, yes, the druid you murdered,” he cordially reminds before returning his attention to Julius. “Ostin excluded her for this and other reasons. She retains a high position among her people. However, she is still a king’s daughter.”

“Clearly,” Julius pushes a cup of wine at Skipio. “Since there’s been no repercussions for her ambushing and murdering my friend,”

“My father,” Skipio interjects.

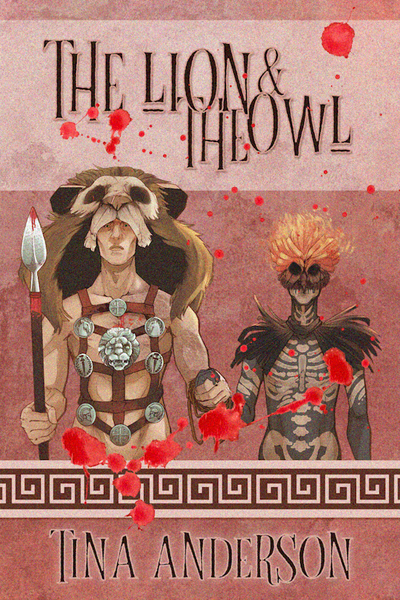

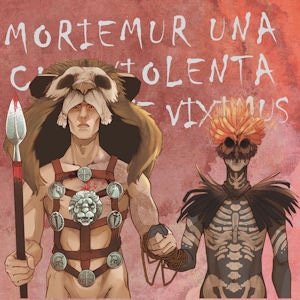

Yes, the Lion, as he’s known to warriors and druids alike, inches ever closer to thirty, his waning twenties lost with his father’s demise. His campaign of brutality against the island’s druids evokes more fear among the locals than the presence of Rome’s legions.

“Our spies say that since Fintan’s death,” Julius fills the Gaul’s cup. “It is her brother Taran who whispers in Cassibelanus’s ear,”

“My source tells me that he’s made her half-brother, Lugotrix, leader of the Ancalites.” Kombius stares into his cup. “Most of the gathering kings disagree with his choice, putting their faith in her son, a young druid that Cassibelanus dislikes immensely.”

Skipio raises his head as if freshly woken. “Why would this warlord dislike a strategist who’s won him battles?”

“Strategist?” asks Julius.

“He speaks of the Owl,” Planus says softly.

“Yes, but Aedan the Owl King is of two extremes,” Kombius tells them. “Cunning beyond measure, and brutally whorish beyond shame,”

“How is one brutally whorish?” asks Planus.

Kombius smirks. “For him, a fistfight is foreplay,”

Julius looks at his Lion and finally understands.

“Is that what’s made you a child seeking a new toy, Skipio?”

The young man remains silent, his thoughts on the deadly druid his own.

“Fintan was a reasonable sort until he married,” adds Kombius.

Planus wonders, “Does anything make a man more unreasonable?”

“Forgive him,” Julius raises his cup. “Planus carries little taste for women,”

Planus says, “I speak of matrimony, not women.”

“Matrimony and women go hand in hand,” laughs Julius.

“How now, uncle,” Planus smirks. “Men also forge bonds in Juno’s month,”

“Despite our laws ignoring such ceremonial unions,” Skipio gripes.

“Are you married, dear boy?” Julius teases Planus.

Pearly teeth peek out amidst a face full of hair.

“If I were, mother would be the first to know,”

“Then I would be the last,” Julius jokes.

Planus and Kombius laugh, but Skipio broods while Labienus scowls.

“Your men have many wives, then?” Planus asks.

“It is our women who have many husbands,” Kombius answers. “Bonds form when life begins,”

Planus blinks. “You’re married to every woman you get pregnant?”

“You Romans and your writs. There’s no need for contracts if proof of your partnership lies swaddled and crying in your arms,” Kombius shrugs his bony shoulders. “I’ve rutted many a man when the mood strikes, but what I leave him can be wiped away or pushed out with a good fart,”

“And with that, I take my leave.” Labienus rises. “I bid you goodnight and thank you for your hospitality, Imperator,”

Julius raises his cup. “Thank you for supping with us, Tribune,”

The man departs, and Kombius sighs.

“I’ve made him uncomfortable,” he says.

“He doesn’t trust you, nor do I,” Skipio reveals. “You left camp this morning without informing the watch,”

“Yes,” Kombius nods. “And you would know, wouldn’t you?

Julius sets down his cup. “What’s this about then?”

“Legate claims our Kombius ventured into the woods without acquiring leave,” Planus explains with hardened eyes on Skipio. “None one brought up it this night, as you dislike camp politics spoken of at supper,”

“Speaking on bonds between men,” Kombius hopes to change the subject by addressing Julius. “You asked me to reach out to an old lover, and that’s what I did,”

“Then why not inform the watch?” Skipio asks.

“Because I didn’t want you killing him,” Kombius snaps. “Each covert meeting I’ve arranged finds you showing up and murdering everyone in attendance,”

“This is an acceptable reason,” Julius decides. “Thank you, Kombius.”

Planus, the consummate de-escalator, stands.

“We should take our leave, Skipio,”

“I trust you, Lord Planus,” Kombius says, taking his wrist. “More than I trust any other man in this camp,”

Julius apes insult. “You too, Kombius?”

“I’m sorry,” the Gaul grins, eyeing Skipio. “You’re still my battle king, but your Legates do not trust me farther than they can throw me.”

“Except for our dear Planus,” Julius baits.

“Full disclosure,” Planus says. “My interests come tainted,”

Skipio tempers his tone. “May I ask this lover’s name, Kombius?”

“To what end?” Planus laughs over his agitation.

Kombius answers, “His name is Taximagulus, he leads the Cassi,”

“And what words did he share?” asks Julius.

“A high-placed woman seeks an audience with Rome,” Kombius tells him. “She wishes to settle hostilities between you and her family,”

“And how does she intend to do that?” Julius wonders.

“She’ll divulge the location of the Catubellauni stronghold,” Kombius reveals softly. “In return, she desires safe passage to Belgica for her and her son.”

Skipio quakes, “The nerve of that bitch,”

Julius raises a hand for him to settle. “Kombius, arrange this meeting,”

Skipio jumps to his feet, silenced by Julius’s hand.

“Planus,” Julius adds. “Go with him to these negotiations, and when you do, inform the watch guard of your exit,”

Kombius stutters, “Caesar, she’s n—”

“I know the woman who seeks this meeting,” Julius assures him. “Go now with Planus and arrange it,”

Kombius departs, concern plaguing his brow, while Planus follows, delivering a wordless warning for Skipio to remain calm. The moment they’re gone, however, the Servian heir takes up his mane-covered helmet.

“You will remain, Lucius Scipio Servius,” says Julius.

He gnashes his teeth. “How can you even think of making a deal with the bitch who killed my father,”

Julius eyes the space beside him. “Sit down, boy,”

“Boy?” Skipio roars. “You’re not my father,”

“Rome is your father now!”

Skipio shakes his head.

“I won’t discuss the needs of Rome over justice for my father,”

“You’re behaving like a wild boar,” Julius shouts. “Must I cage you like one?”

Skipio comes to attention.

“Apologies, imperator, for my lack of respect.”

Julius sits up and pats the space beside him. “That’s better, now sit,” and as Skipio moves to do so, he scolds, “Put that damned thing on the floor,”

The fleece-covered helmet finds a place between their feet.

“Take a breath and count to ten,” Julius orders softly, but when Skipio sighs in frustration, he barks: “You’ll do it, Or I’ll send those eyes rolling out of this tent,”

Skipio swallows his pride, takes a breath, and, in his mind, counts to ten.

Julius joins him, the scent of bacon and barley finding him from the half-empty plates. No doubt, thoughts of the Owl and his bitch mother boil within the man beside him, but hopefully, this momentary settlement will dampen his fire.

Julius leans down and pinches an ear on the lion’s head.

“Did your father ever tell you where this came from?”

“A beast from Bithynia,” says Skipio.

“It was our first campaign together,” Julius nods. “I was younger than you in those days, but I’d allied with the wrong people. I was desperate for a high position in the House of Jupiter,”

Skipio turns to him. “You were a high priest of Jupiter?”

“Oh yes,” says Julius. “Until those that got me there picked a fight with the wrong man. They lost, just as my mother said they would, and for that, and for refusing to divorce my wife, the victor exiled me to military service,”

“You never chose to serve?” asks Skipio, shocked.

“No, and neither did your father,” Julius tells him. “He’d gambled away your mother’s dowry and needed a soldier’s pension to get it back.” Julius raises a finger. “He never gambled again. Your father made mistakes but never made them twice.”

Skipio lowers his gaze.

“Back in those days,” Julius continues. “I dabbled in men on occasion, not like you and Planus, who live for cock like it’s your religion. Knowing this, my legate sent me to negotiate for ships at the Bithynian court.”

Skipio provides his full attention.

“Your father came along because he was a sturdy hairless sort,” says Julius, grinning. “The type their King fancied,”

“Did my father—?”

“Bye-Jove, no,” Julius laughs. “I did the heavy sitting on that mission, and thanks to your father prancing around half-naked, the King proved a rather uncomfortable chair,”

“Father never spoke of his time in the east,”

“It’s not the sort of thing a man tells his son,” says Julius. “Our host, the Bithynian King, kept a lioness in his menagerie. She came from lands far south of Egypt, and Vitus brought one of her cubs back home. Your grandfather—”

“—Red,”

“Yes, old Rufus.” Julius grabs the decanter and drinks from it. “Rufus named that cub Leonidas. Taught him to take down deer and boar that got into the orchard,”

Dried blood dots the fleece’s ears.

“I saw the beast many years later,” he says, offering Skipio a drink of his wine. “Your grandparents threw an orgy to celebrate your birth. Cornelia was pregnant then, and she desperately wanted to hold you,”

Taking back the decanter, Julius empties it with one swallow.

“We didn’t know that shortly after your birth, Leonidas had gone peculiar. The beast had mauled some harvesters and then attacked two horses.” His fingers scratch into the fleece’s stiff mane. “That night, after we’d gone to sleep, Leonidas climbed out of his pit, entered the house, and killed your wetnurse.”

The lion’s snout stares back at him, its whiskers broken and bent.

“Your grandfather died protecting you. Vitus and I nearly died taking the damned thing down.” Pain clouds his memory. “Cornelia lost her baby that night. A boy. What there was of him in her piss bowl, we buried with your grandfather,”

Remorse colors Skipio’s face. “I’ll burn it, Imperator,”

“You will not,” Julius says, patting Skipio’s knee. “This thing meant too much to your superstitious father. He brought it on every campaign. He said that Minerva came to him in a dream, telling him that the beast that tried to devour his boy would protect him when grown.”

Skipio’s eyes pool with water. “I remember one winter, the snow came early and made a white mountain in the impluvium. Father gathered handfuls of it and lobbed it at everyone in the atrium,”

Julius runs a paternal hand across his back.

“I remember this one Saturnalia, father wore my mother’s womanly robes and jokingly swaddled Vita.” Skipio wipes his nose. “My first harvest, it went on long into the night. Father the lion’s mane and put me on his shoulders. I swung at all the low-hanging fruit with my grandfather’s stick,”

Julius puts a hand upon the young man’s shorn head.

“When I see you in this, Skipio, I see that lion gone mad,” he tells him. “I’m begging you, as one who also mourns your father, please, get ahead of this madness. Do not make me put you down the way we did this damned beast.”

A low groan escapes Skipio’s throat before fierce sobs cover his chin with spit.

“There it is,” Julius’s arm curtains those broad shoulders. “That’s what Roman’s do. We weep for those we lose, not rage for what we’ve lost.”

Skipio cries for several moments.

“You cannot let anger consume you,” says Julius, releasing him. “Not when you must take your father’s place in Comum,”

Skipio’s head rises. “Comum?”

“You’re going home,” says Julius.

“I can change.” Skipio jumps to his feet. “I will change,”

“It’s not a punishment, boy,” Julius assures him.

“There’s no reason to send me home,” Skipio says. “Not when I’ve proven myself capable on the battlefield,”

“The Senate has stripped the people of Comum of their citizenship.” Julius stands with him. “Even families founded in Rome are not immune,”

Skipio’s mouth opens. “Why would they do such a thing?”

“Resentment and jealousy,” Julius tells him. “Comum’s representative in the Senate, your father’s cousin, killed himself after being whipped like a dog in public by Marcus Claudius,”

Skipio growls, “That arrogant Claudian bastard,”

“Arrogant, yes, and powerful.” Julius grasps his muscled arm. “This is why I’m making you Tribune of the Comum battalion,”

Skipio recoils.

“I cannot accept such a high position,” he says. “I haven’t been a praefectus yet,”

“Madness has ruled you for too long,” Julius chuckles. “Do you think I would’ve allowed a simple decurion to lead the missions you’ve carried out these past weeks?”

Skipio’s mind turns behind distant eyes.

“You’ve been Praefectus Vigilium for some time now,” Julius reveals. “You and your riders have protected the marching legions far better than we’ve deserved,”

“But, Caesar,” Skipio whispers. “I’ve only hunted druids for personal—”

“—You’ll wear the purple stripe,” Julius interrupts. “Rebuild the garrison at Comum, and from there, aid Crassus Titus Flavius in Mediolanum and our dear Planus in Bellagio.”

“Comum houses so many youthful trainees,” Skipio warns. “They know more of work than weapons,”

“Marcus Castor Junius will use the youth in rebuilding Octodurus,” Julius decides. “Those going home with you will reestablish the road-watch network and protect our colonial loyalists,”

Skipio comes to attention. “I will not fail you, Imperator.”

“No,” Julius grips both his shoulders. “You must not fail Comum.”

Comments (6)

See all