Bisi wandered the museum for a little while longer and then claimed a seat at the bar where she could watch Marisol flit from space to space, from crisis to crisis for the next few hours. She was like the tiny hummingbirds that came to the feeders at Bisi’s home in Baltimore— small, lightning fast, and jewel-like. At home, in Nigeria, they had many beautiful birds, including sunbirds that drank from flowers and glittered in the light like precious stones, but they did not not dart from place to place, moving in every direction on almost-invisible wings. Maryland’s hummingbirds fascinated Bisi endlessly.

The first hummingbird Bisi had ever seen in person had surprised her while she was seated outdoors at a coffee shop. The little bird had come to visit the planter full of little red trumpet-shaped flowers that was hanging over Bisi’s head. At first, she had taken it for a very large insect, and had been about to vacate the table— you could take the girl out of the city, but you could not take the city out of the girl. Bisi had no great fondness for large flying insects. Then a second had joined it, and she’d gotten a closer look—a bird! A bird barely bigger than her thumb!

Bisi had then watched as the two birds entered into aerial combat over a flower, even though there were countless other flowers on the plant to drink from. They hurtled themselves at each other, squeaking in annoyance. So, they were tiny and delicate…but fierce. This endeared them to her completely. She’d stayed for almost an hour watching the birds come and go, sipping and squabbling. As they moved in and out of the sun, their throat feathers would glow and gleam like embers. She’d gone home and had read up on the internet about hummingbirds. The next day, she’d gone out to purchase a feeder and nectar and set them up on her porch so she could enjoy the show from her own patio that first spring and summer.

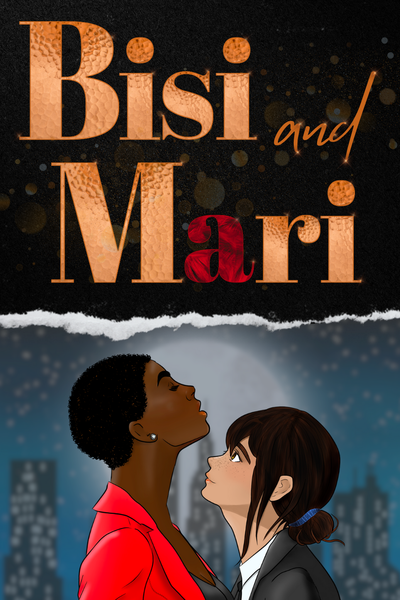

Marisol reminded Bisi less of the lovely little emerald-green Ruby-throated hummingbirds, and more of the ferocious little Rufous birds with their warmer palette —amber and topaz, carnelian and onyx—but still that flash of vivid red. Marisol’s severe suit, her pinned up hair, her crisp white shirt, they were all designed to help her blend into the background. The plush, vivid red of her lips, however, offered a tantalizing insight into who she was beneath the professionalism. It was as if Marisol could not resist drawing attention to that one aspect of her stunning beauty. Bisi suspected that she was not, at heart, a woman who was satisfied to go unnoticed or be dismissed. The flash of temper in Marisol’s eyes when Halston Hollis had been snappish with her made it clear that she would have cheerfully darted through the air at the irritable little star if she had not been restrained by duty and dignity.

Bisi had two more Old-fashioneds as she waited, the second of which the bartender had made before leaving for the evening, and had kindly used a whiskey ball so it would not be watered down by the time she was ready for it. She welcomed the warmth of the bourbon, and the calming of her sense of urgency, but she paced herself. She did not want to relax too much and say or do something clumsy. She would not easily get a second chance if she did not win Marisol over at least a little this evening. Marisol had thought she might leave? What Alpha would leave someone whose scent poured through them, warm and spiced and sugar-dusted? Who zipped through rooms, smoothing away problems with a quiet word, a gesture of the hand, a quick smile. Who sparked with energy as she directed a small army of workers unerringly all while the oblivious guests danced and drank and laughed and enjoyed the fruits of her invisible labor. What Alpha could leave such an Omega? Not Bisi, certainly.

From time to time Marisol would dart a quick look at her, favor her with a flash of white teeth and red lips and each time she did, little thrills ran over the surface of Bisi’s skin. As the number of guests thinned, Bisi’s appetite for Marisol’s presence was sharpened until Bisi realized that her hand was gripping the top of her thigh, her nails digging into her skin through her trousers. “Patience can cook a stone, Bisi,” she muttered to herself.

Her phone vibrated in the interior pocket of her suit and she extracted it. A text, from Marisol.

<Marisol Ortiz> Still there? Fifteen minutes or so and I’ll be free.

Bisi typed a very affirmative response and then deleted it and typed a normally affirmative response and sent it. Fifteen minutes was nothing. A fraction of the amount of time she had already waited, but it stretched out like an eternity in front of her. She sighed. She checked her email again. Nothing new. She checked the weather. Chilly and damp. Surprise. Bisi had grown up with plenty of humidity during the rainy season in Abuja, and it could get quite cool at night during the dry season, but until she moved to Baltimore, Bisi had not been fully prepared for what happened when you combined even moderately cold weather with high humidity. Even in New York, the cold had not felt like it did in Baltimore. The wind whipping off of the Chesapeake Bay sliced through clothes and flesh like a scalpel, chilling not only your bones but the marrow inside them. Although the wind came off of the Potomac in DC, the effect was very much the same. She checked the time again. Only one minute had passed. Shit.

Eleven very closely-watched minutes later, Marisol appeared, three minutes ahead of schedule. To a person who had not been closely monitoring her all evening, she looked much the same as she had hours earlier. To Bisi, who had made a study of her, she looked a little frayed around the edges, but also a little lighter with the relief of having successfully completed a massive undertaking.

“Finally, I’m done! I can’t believe you stuck it out!” said Marisol, smiling widely at Bisi. “We’re free. Think we can find a decent place to get a drink at this hour?”

“Ah, well, I found one for us. I had a little time on my hands to consider our options. You aren’t too tired, Temi? I’m tired just from watching you run around all night,” Bisi asked, because it was the decent thing to do, but every part of her tensed as she waited for the answer.

“No! I mean, I am tired, obviously, but not too tired. I have been looking forward to this. Are you too tired?”

“Marisol, I would have to be dead to be too tired to have a drink with you. Even then, I hope someone who had really cared about me would prop me up and stick a drink in my hand.”

This startled a laugh out of Marisol, a real laugh, an off-duty laugh, the first Bisi had heard from her, and it was like the caress of a warm hand on her ego. Yes, yes. More of that, please.

“Mari,” said Marisol.

“Hmm?”

“I’ll call you Bisi, but you have to call me Mari. Not Marisol.”

One minute in, and Bisi had already been allowed a small liberty. This was going so well! “I can do that. Your name is very lovely, by the way.”

“Ah, well… I mean, I like it, but it’s kind of a downer, meaning-wise. It’s a shortening of María de la Soledad. Because Mary sat alone the night after her son was crucified. Very Catholic name. But… it does also sound like mar y sol, which means ‘sea and sun,’ so that’s a more cheerful interpretation. What about Bisi? Does it have a deep, dark meaning, too?”

Bisi chuckled. Well, she asked… “Wellll, not deep and dark, but it has a meaning. It’s Yoruba. It means ‘to multiply’,” she answered with a wink. “Wishful thinking from parents who want a lot of grandchildren, I think.”

“Oh, well, maybe it’s better to just front-load all the nagging right into your name so you don’t have to discuss it with every single phone call home.”

“Oh, I still have to discuss it with every single phone call, Temi, believe me. Becoming a heart surgeon is eh. Grandchildren, though… ”

“Oh, I get it, trust me. So, you’re from Nigeria? I saw it in the security firm’s notes earlier when I was checking the guest list to find a doctor. I wasn’t trying to pry, it was just there—”

“I don’t mind at all. It’s hardly private information. I’m from Abuja, the capital, and that’s where my parents and one of my brothers live. My other brother lives in Lagos and my little sister lives in Los Angeles. I'm the eldest.”

"Ah, ok. How long have you been living in the US?”

Bisi wrinkled her forehead, calculating. “Oh, a long time now. Almost fifteen years. I came over for graduate school when I was twenty-one. I did a master’s in biochem and then I went to medical school at Columbia. Then residency, then a fellowship… and here I am.”

“Well, I am not especially well-versed in Nigerian culture, but I do love jollof rice and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s novels and people talking about their ‘Aunties’ on social, which I find pretty relatable because I come from a big, loud, nosy, extended family. I like Luvvie Ajayi Jones’s books and blog, too. She’s smart and funny.”

“Well, those are respectable pathways to understanding Nigerian culture to start with, especially the jollof rice. I’m quite impressed that you can spit out Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s name so fluidly. And correctly.”

Mari shrugged. “I mean, Americanah was a really good read. I watched some interviews with Adichie and made a note of her name, I didn’t intuit it or anything, so I’m not sure there’s any reason to be impressed.”

“Maybe it’s more impressive that you cared to find out how to say her name and bothered to remember than that you intuited a pronunciation,” countered Bisi.

“Bar’s low, then?” Mari laughed. “Well, of course I want to know. For myself, but also for work. I coordinate people, places, information, materials, services… I work with people from everywhere and from every walk of life, from delivery people to hotel owners to the occasional celebrity, as you saw tonight. Cater-waiters or diplomats, I need to show all of them the basic respect of learning to pronounce their names if I want to have a good working relationship with them. So, when I come across a new name, I learn how to say it. It’s just part of my job.”

“Are you trying to argue that this philosophy or this interpretation of your work duties makes you less unique and not more unique? Mari, it pains me to disagree with you, but noooo. I love Nigeria, but I also enjoy living in America very much most of the time, and I’m not sure which state you are from—perhaps one I have not visited—but I haven’t noticed that a passionate interest in other languages and cultures is part of America's national personality.” Bisi laughed, rich and low.

“Ah, well, I’m not from a state. I’m from Puerto Rico. So, in every legal sense, that makes me American but in the eyes of some people, not so American. Maybe that’s the secret of my success…I hang out in the liminal spaces, so my curiosity about the world is intact.”

“Ah, interesting. I met a lot of people from Puerto Rico when I was living in New York. Arroz con Gandules is very good— maybe not as good as jollof rice...” Bisi’s voice trailed off, baiting Mari to see what would happen.

Mari’s mouth popped open. “¡Oye! Ten cuidado! Those are fighting words!” Mari interrupted, her jaw jutting forward in theatrical umbrage.

Bisi grinned. Oh, she’s so fun! “No, no. Let me live! I am teasing you. Shall we head out? The bar is in a hotel that's just a couple of blocks away, so we can walk. Or I can drive us or we can meet there…”

“Walking is fine. Let me grab my coat on the way out, though. I’m always freezing this time of year,” said Mari.

“Me too,” said Bisi, in heartfelt tones.

“Drinks are on me, by the way,” Mari announced, “I owe you at least that much for helping me out with that... gentleman. And for waiting for me.”

Bisi made a supremely disapproving sound. “You think I invite a beautiful woman for a drink and then let her pay for it? Not likely, Arewa.”

Comments (0)

See all