Victory and Bard kept to the back of the group as a bored woman from personnel led them around Palmer Manufacturing’s factory. Victory had exchanged her black leather jacket for a respectable charcoal gray blazer, but she still looked incongruous among the machines that clanked and whirred under the fluorescent lights that skimmed the scratched surfaces of their plastic safety goggles. The factory was so vast—concrete-floored, industrial green-walled—that it hardly seemed to be an indoor space. Palmer Manufacturing machines made parts to make more machines. It was Milton as an industry, Bard thought—men like his father, like Victory’s father, men who made Milton run, siring children whom Milton would claim. But with Milton in his veins, Bard wanted to give it a voice that was not the sound of steel on steel or the roar of coal furnaces, wanted to carry Milton with him, leaving the place itself behind. Someday. For now, he would put in his six weeks here, then return to his life bound by the four walls of his bedroom or anonymous bodies listening beside him in dark clubs.

Bard’s and Victory’s training wasn’t in the factory. They were tucked away in the beige and burnt orange offices where the thin light was filtered through the grime on the windows and the dominating sound was the clacking of the typewriter pool. Bridget had been in that pool, more than twenty years before. Bard imagined her, strawberry blonde and fresh-faced, falling under the covetous eye of Roger Fox.

Bard worked in the cluttered technical writers’ room, a stack of style manuals that would teach him how to write manuals on his desk. The men in the office wore white shirts and ties without jackets, wire-rimmed glasses (as opposed to Bard’s staunchly National Health Service tortoiseshells) and wrote copy on manual typewriters that they then marked up and handed off to Bard to be retyped. He took the finished copy to the art department, where Victory sat on a stool at a drawing board, the only woman in a room full of men who drew with T-squares and rulers. She’d hung a rubber snake on the goose-neck lamp clipped to her desk. There, she and Bard whispered to each other under the suspicious eye of the intern supervisor, Mr. Barkley.

Mr. Barkley could tell them off but not fire them; their fathers avoided them; and they were fine with that. They took their breaks on the roof if it wasn’t raining, looking out over Empire Street. That’s where, in between Bard’s instruction manuals and Victory’s technical illustrations, they produced a series of “Impossible Machines”—the Poetry Engine and the Flower Assembler and the Music Mill, the Soul Extractor and the Self-Terminator and the Groupthink Gin. And that’s where they were when, three weeks into the six-week internship, Bard squinted through the rare sunlight to look at the record shop on the corner.

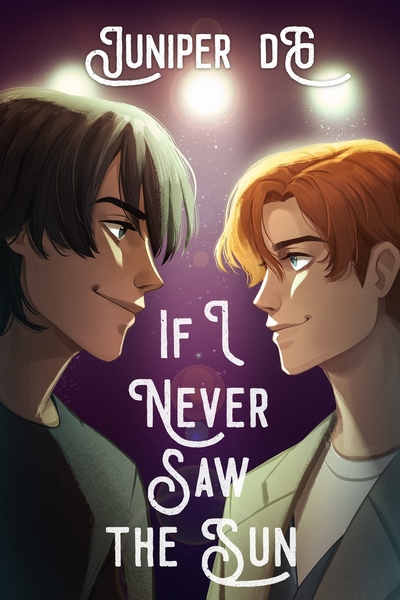

“Wait... who is that?”

Victory sidled up to him, shading her eyes. “The ginger? Girl from St. Mary’s skiving off school, looks like. Too young for you, Bard. Don’t be a lech.”

“Really, Vic,” Bard said, cringing. “The girl is my sister, Cassandra.”

“Sorry.” She dug a pair of mirrored sunglasses out of the pocket of her wool overcoat and put them on. “You mean the boy with her? Tall one, dark hair?”

“There’s only one boy with her, so, yes.”

“Ah, so that’s your type, then.”

“No. No. I don’t have a type. I want to know who is hanging about my sister.”

“So ask your sister. I don’t know him. He looks older than her, though.”

Bard peered down again. Cassandra was talking, gesturing wildly, and the boy was leaning against the brick wall, nodding, making a brief remark here and there. He was tall, maybe even taller than Bard. His black hair was a mass of tousled waves; he wore a black leather jacket and cuffed jeans. But he didn’t have the cocky affectation of most boys putting on the postwar delinquent look. Something about his posture and his gestures—his body bent toward Cassandra so he wouldn’t tower over her—seemed gentle.

Victory peered over his shoulder then turned to look him in the face. “You’re licking your lips,” she said.

“They’re chapped,” he replied.

“Likely story. C’mon, break’s about over, and you don’t want Barkley having a go at us with his clacky dentures and horrid breath.”

“Right—Bard said, distracted. “I’m just going to—check on—”

Victory nodded and waved him off. “Right, check on your sister.”

Comments (0)

See all