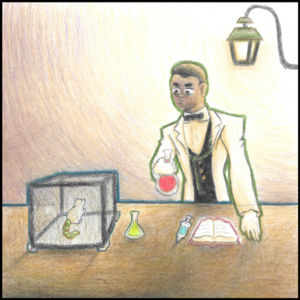

His name was Harold Baker. He was 19 years old. And that’s all you need to know for now.

He waited patiently for his friend—the red-headed boy sitting across from him at the table—to finish his tirade. Actually, “friend” was a little too strong. Companion, maybe? Yes, that seemed right. Sure, they shared a room together at one of the Institute’s dormitories, and sure, they spent a lot of time studying together, but in Harold’s opinion, that was no reason to consider him a “friend.” After all, he’d never had one of those before, so why start now?

The not-friend’s name was Theodore. Short and scrawny he was, with a round face, large, drooping blue eyes, and a mischievous smile that made him look quite out of place at a school that was supposed to be one of the most prestigious in the country. Had he not known better, Harold would have thought that Theodore was several years younger than he was—which made the fact that Theodore was technically older than himself all the more difficult to believe.

As usual, Theodore was going on a tirade about something that no one else in the world knew or cared about. It would have been quite boring, except for the fact that Theodore was an unusually expressive individual; his face, hands, and tone of voice all seemed to say almost as much as his words did, and with a such a flamboyant, overly-exaggerated flair that one couldn’t help but become engrossed in what he was saying, no matter how ludicrous; and so, as usual, Harold found himself being drawn deeper and deeper into the conversation.

“All I’m saying,” Theodore exclaimed in what Harold had come to recognize as a New Yorker’s accent, “is if you’re gonna let pegasi and unicorns into horse races, you might as well go the whole hog and allow any kind of mutated abomination!” One of the other students studying at the library shushed him, and Theodore continued on in a voice that was very slightly quieter. “Hell, at that point, why not just get an elephant on the track and ride that? As long as it has four hooves and a tail, it’s fair game, right?”

Elephants didn’t have hooves, but Harold didn’t bother correcting him. “Not comparable at all,” he said instead. “Genetically speaking, unicorns are nearly identical to horses. The addition of the horn changes nothing about their overall physiology, except their appearance. Elephants, on the other hand, aren’t even a kind of ungulate.”

“Ungu-what? Whatever, I don’t care. Fine, I’ll give you unicorns. But what about pegasi? They’ve got giant freakin’ bird wings! How is that allowed?”

Harold shrugged. “As long as they don’t use them during the race, what’s the difference? Actually, I would think that the addition of wings would make them worse runners.”

“Oh? Then explain this!” Like a magician, Theodore made a copy of the Wyvern’s Eye, the official newspaper of the Xantrak Institute for Neogenic Research and Discovery, appear out of seemingly thin air. He spent a few seconds flipping through the pages before holding up the paper for Harold to see and pointing an accusatory finger at the offending words. “Stormcloud the pegasus takes first place at the annual Derby of Albion.’ How’s that for a ‘worse runner?’” He was hushed again, but he had already made his point, and so instead of lowering his voice he took the opportunity to look smug.

In response, Harold reached over to a nearby shelf and pulled out a book titled Avian Biology and the Human Alteration Thereof. He had already read most of the books in this section of Carter Library more than once, so he had no problem finding the right page. “‘In short, the Baird process’—the same process that created Stormcloud, mind you—‘is remarkably simple and efficient, but the incredible metabolism possessed by birds is something that must always be taken into account.’ Stormcloud may be fast, Matheson,” Harold used Theodore’s surname precisely because he knew it would annoy him, “but the poor thing was also probably starving. Almost all bird hybrids are in a perpetual state of hunger. If those other horses couldn’t beat a literally starving animal, it probably says more about them than Stormcloud.”

“And how exactly do you know they used the birdie experiment or whatever it’s called on this Pegasus?”

“Because the Baird process was specifically designed to be as straightforward and repeatable as possible. You’d be an imbecile not to use it. It’s the same reason why all winged hybrids have bird wings. It’s just the most convenient option available.”

“I’m pretty sure they’ve got bat hybrids now.” From his tone and the way his shoulders had frozen up like a glass of wine left in the arctic, Harold could tell that Theodore didn’t actually have an argument anymore; he was just being contrarian. “I read about it in the paper.”

“Not that it matters, since Stormcloud is part eagle, but I can say for a fact that you didn’t. Bat DNA is notoriously difficult to replicate. If there’s a neogenic creation out there that’s flying around on bat wings, I’d certainly like to see it.”

Just at that moment, the relative silence of Carter Library— which had already taken a hit as soon as Theodore had walked through the door—was utterly demolished by the sound of stone rending and glass shattering. It didn’t take long to locate the source, which happened to be a massive lion with a bloody maw and a ferocious countenance. It had, apparently, flown in through the window, taking some of the wall with it as it tore its way in. It also, quite notably, had a pair of large bat wings on its back, and as the behemoth landed in the center of the library, the draft created by their flapping sent dozens of research notes and ill-placed essays scattering away like a group of burglars at the scene of a robbery.

Theodore stared blankly at the monster for a moment before turning to Harold with a self-satisfied expression on his face that belied the danger of the present situation. “You were saying?”

Comments (0)

See all