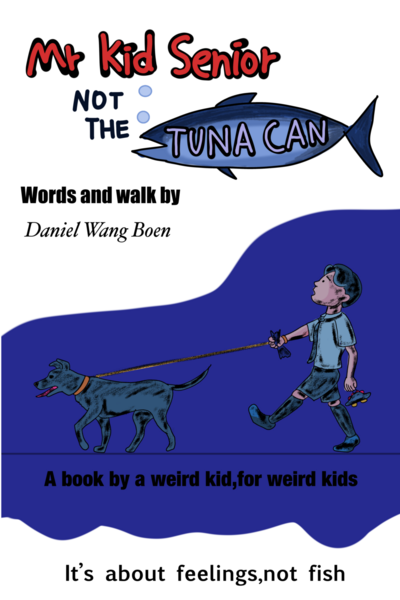

Chapter 18 – "Puzzles"

It was clear that without my parents’ interference, there’d be no progress in my treatment—not that they’d make things any better if they did interfere.

But the process had to run its course.

Now I’m sitting in the waiting area of the H33 Psychological Medicine Department, with my parents and Gary, my case manager.

We’ve each claimed a chair, leaving an empty one in between—distancing ourselves physically and, more importantly, mentally.

Everyone looks tense. Everyone except me.

Whatever happens, I won’t be surprised. Expected.

The speaker calls for the next number. Everyone looks up. Not me.

We all drop our eyes again—to our phones, our hands, or straight into the void—while

some cursed 2015 toy-unboxing YouTube video echoes through the room, scraping against what’s left of our sanity.

Mom is flipping through my travel log notebook, laughing at the doodles. I’m just glad she can’t read English—otherwise the paragraphs in there could traumatise her for life.

“等一下你就笑不出来了,” I warn her with a smile so dry it looks worse than a weeping face.

Finally, we’re called in. Gary ushers me into the room first, separating me from my parents.

The doctor’s there. If I was anxious the last time we met, this time I’m practically slouched into the chair like I own the place.

I’d done a four-page breakdown of her after our previous appointment. I was angry. Couldn’t find much about her online—just enough to conclude that she’s doing

her job and I’m probably the desensitised one.

“Anything you don’t want your parents to know?” she asks.

“Well, I’d rather they didn’t know about the abnormal tendencies and… the attempts. But do what you must. I don’t mind.”

“Alright, we’ll try our best to respect that. We’ll have a follow-up appointment in a few weeks.”

“You mean eight weeks?”

At this point, I don’t expect my parents—or anyone—to understand.

The emotional toll of this stuff is something I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy. Why am I even thinking like my ancient Chinese birth-giver might suddenly be able to acknowledge it?

They bring my parents in. The doctor explains what GD is, what comes with it—blah blah blah.

My dad, weirdly, seems chill. Even volunteers details: apparently I was telling everyone I was a boy before I could walk straight. He’s “totally fine” with “whatever” I want to become as long as it doesn’t involve him—which earns him a solid round of side-eyes from my mom.

Where my dad’s attitude is basically, Well? What can I do?, my mom’s more of a defy-all-odds type.

“Can you turn my daughter normal? Can you mentally heal her back to normal?”

“I’m a doctor, not a magician,” the doctor says.

I nearly choke holding in a laugh. An hour in and Mom’s still managed to miss the entire point.

I can’t even bring myself to care. Gary invites me out while they have Adults Only time.

I’m back in the waiting area, swinging my

legs, trying to touch the floor with the tips of my shoes. I listen to other people’s problems. Each one sounds like one of mine.

When they finally emerge, Mom’s crying. She says she just can’t accept it. She doesn’t have to.

Gary takes me into his office, pulls out a stack of A4 paper, starts shading a sheet, then slides one over to me.

“Let’s tear some paper,” he says, then takes a deep sigh. It sounds like defeat—or relief.

“Must be really stressful, if it’s got you tearing paper now.”

I fold my paper in half. Then again. I make sure the edges match perfectly.

I tell Gary I get it—everything, and maybe nothing. My dad’s old; he’s almost lived a whole life. To him, 17 might feel far too young to decide anything. I’m sure he’s made mistakes at that age—mistakes he

still regrets.

As for my mom… it’s okay. I don’t want to torture her more than I already have.

Gary says he’ll see me soon. That’s it.

I don’t know what they talked about in there. I don’t care.

After the appointment, I give my parents space and take myself elsewhere.

I feel like a criminal—like I’ve committed some great crime.

I drift aimlessly on the MRT, station to station, line to line.

“Next station, Haw Par Villa.”

Suddenly I’m sitting among all the 妖魔鬼怪—monsters, demons, ghosts. Not a living soul in sight. The statues look like people at first, until you notice one with a snake’s head.

National Day songs play faintly from speakers, making the atmosphere even stranger.

I take out my travel notebook and sketch the huge Guanyin Bodhisattva sitting peacefully in a circle of water.

I vaguely remember Mom telling me Guanyin can help people escape suffering, grant wishes. I’m a child given by her, apparently—but I know I came from Dad’s balls.

I walk closer. There’s a table with a metal 功德箱 for $1 donations. I wonder how many people think it’s worth it.

I shake the box—it’s locked. A sign below says: “Theft is a serious crime.”

No… that’s not—

“Guanyin? You just help people because they ask? They don’t offer much back, do they? Kind of selfish of them, don’t you think?”

I squint up at her face against the bright sun. She just smiles gently.

“Not a talker, huh.”

I sit down.

“Would be weird if you actually did talk back.”

I leave—not because I’m done, but because the place isn’t great for horizontal activities. I haven’t slept.

I’m supposed to get off at Bugis, but somehow I’m at Commonwealth.

Where am I?

Why does it matter?

I keep walking. Pass a school. Basketball girls are running around in skirts shorter than my lifespan.

The bell’s just gone—kids pour out of every doorway, bunch up at the traffic lights.

Some glance at me.

What?

“Oh no…”

My pants aren’t zipped. No idea when they came undone—or if they were ever done up. I zip them while twenty kids watch.

I’m three years older than them, on average—they probably think the opposite.

Across the street is the Queenstown Public Library, old enough to look like a heritage site. My kind of place.

I stumble in. See the stairs. Almost face-plant, but grab the railing just in time.

Photos line the wall—children in the ’80s, proud shots from when the place opened in the ’70s as Singapore’s first fully air-conditioned library.

I realise how much hasn’t changed.

Then I spot it—a puzzle.

Small table, two chairs. Unfinished puzzle. A sign:

“Contribute to the puzzle. Stick a sticker to let us know.”

I would LOVE to stick a sticker.

So I sit. Start working.

Half-awake, not sure how much time passes. Two kids stand behind me, silent.

I turn, pull out the spare chair. They bolt.

Fine. Back to work. It’s not about the sticker anymore. I need to solve this.

Ten minutes later, one of them’s back—a boy, maybe eight, thick glasses. A future nerd.

I gesture at the chair.

“Help yourself.”

“No thanks.”

He skips away.

The puzzle’s supposed to be a square. Mine turns into a rectangle.

“Why isn’t it the same? There’s a reference right there. How did I get it wrong?”

“Uh, you’ve been here for half an hour,” the boy pipes up again.

“I have issues.”

He skips off.

I finish the puzzle. Feel nothing. Stick a sticker. Still nothing.

I mess up half of it again. Sit a short

distance away, watching it like it owes me money.

A woman in a sports bra and tight pants finishes it.

The librarian comes by and messes it all up again.

Something in me aches.

More kids try. They give up.

Should I do something?

Nah,I need five minutes.

Comments (0)

See all