Dusan was twelve when he met his first airie. The encounter left him with scars, and the burning question of whether the creature actually tried to kill him.

They gathered wood on that day, not far from the village. He could see the distant smoke from the cooking fires rising over the treetops. He imagined he could smell the food, too. He was pretty hungry already. He had done some fishing in the morning, with Mirche and Zora, and then they had played hide and seek, and then, when too many smaller kids had joined them, and the noise they’d been making had begun to bother the adults, they had been banished to gather wood. The three of them had played some more in the forest, and were now making up for the lost time, gathering what they could. He was tired, and anticipated getting home, eating whatever his mother had cooked, and warming his freezing feet by the fire.

Freezing? The sun was still high, and the summer air was warm against his cheeks, but his feet felt cold. He frowned, puzzled by this inexplicable phenomenon.

“Are you coming?” called Mirche. “We’re going back.”

“Yes,” said Dusan. “Coming.”

Yet when he tried to move, the feeling of cold intensified. He looked down and was surprised to see the fabric of his breeches flap around his ankles as if a strong wind was blowing. Yet against his face, the air stood perfectly still. Confused rather than scared, he bent, reaching down.

Once his hand was at the level of his ankles, a freezing wind hit it, making him straighten back up quickly. He could see now that the grass was lying almost flat around him. As he watched, it began to cover with frost.

He heard a sharp cry and looked up. Mirche and Zora stood at the edge of the clearing. Zora’s bundle of wood lay scattered on the ground. Her hands were pressed to her mouth, her eyes wide with shock. Mirche’s expression was only marginally less scared, and Dusan fear finally broke through his confusion.

“Run!” Mirche yelled. “What’re you waiting for? Run!”

Dusan couldn’t. An attempt to move resulted in sharp pain in his legs. He looked down and saw his breeches beginning to turn white with frost. His legs were literally too frozen to move. He could barely feel them anymore. He looked up to see Zora disappear behind the trees. Mirche backed away, following her.

“It’s an airie!” Mirche yelled, pointing somewhere behind Dusan. “An airie is putting a spell on you! Hang on, I’ll bring help!”

With that, he turned around and ran. Dusan wanted to call after him, but the pain in his legs was by now too overwhelming. He was going to fall, he knew, and then this strange wind that blew low above the ground would consume him and turn him into an icicle.

An airie is putting a spell on you.

He looked around and, just a few steps away, he saw him.

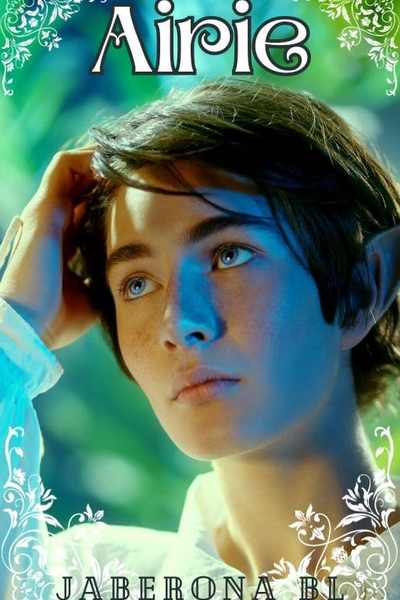

The boy stood by the bushes at the end of the clearing. He was about Dusan’s height and probably about his age—if air people even aged like normal ones. Dusan knew it was an airie even though he’d never seen one before. The boy looked ethereal, his skin too clear, his clothes too spotless, too unfamiliar looking. He was nothing like Dusan and his ragged, eternally dirty-faced friends.

He was also smiling.

Despite the pain in his legs, Dusan was momentarily captivated. Having heard many tales about the air people, it was amazing to actually see one. The boy’s face was perfect. His smile was beautiful. Dusan tried to take a step toward him, but the pain in his legs intensified, and he had to throw his hands up in the air to keep his balance.

That reminded him that it was the airie—this boy—who was making this happen.

“Why’re you doing this?” Dusan said.

The boy’s smile widened, and he tilted his head as if in contemplation.

“Because,” he said, his voice as pleasant as his features, “it’s entertaining.”

“It’s hurting me!”

“It does,” the boy said, a note of curiosity in his voice, “doesn’t it?”

“Can you stop it?”

“I could,” the boy said, but the pain in Dusan’s legs remained the same.

“Will you?”

“I might,” said the boy, tilting his head to the other side. “Or not.”

“Hey!” someone yelled. “You damn creature, leave him alone!”

Dusan turned and saw his father appear from behind the trees, brandishing a thick stick. For a moment, Dusan was terrified that he would also be engulfed by this wave of cold. He shot a glance at the boy who, indeed, seemed thoughtful for a moment. Then, he shrugged and stepped back, the smile never leaving his face. As Dusan’s father ran over to where Dusan stood, the airie disappeared behind the bushes.

Dusan looked down and saw that no wind disturbed his clothes anymore. He couldn’t feel his feet, though.

His father caught him before he collapsed. He sat on the ground, hugging Dusan, then rubbing his frozen feet, his touch not quite getting through Dusan’s numb skin.

“That bastard,” his father kept saying. “I thought they were gone for good. Haven’t seen them in ages.”

“He was pretty,” Dusan said, feeling dizzy.

“Pretty? Oh yes, they are, but they’re mean and evil. I thought they were gone from this area. We should spread the word, let everyone know that one is back. We have enough trouble from storms and cold and the heat even without those abominations creating them on a whim.”

“How do they even do that?”

“Who knows? Manipulating the air, somehow.” His father stopped massaging his legs and caught Dusan’s face in his palms, forcing him to meet his eye. “Air people, aren’t they? You should always have something with you—a knife, a stone to throw, a stick. They’re cowards. You open their skin, their abilities flow out with the blood. They never come close when they know you have something to cut them with. You must remember this—when you meet an airie, you cut them open.”

Comments (0)

See all