“Shall we go to the Leech Valley, Amma?” It was the third

time that Jasmine had asked the same question.

It was a sunny afternoon. The kind of day that tempted you

to celebrate, even when you didn’t feel like it. Usha relented.

“Okay, Thangam,” she said. “Put on your sandals and we will

be on our way.”

Leech Forest lay about a kilometre and a half further up

into the mountains. It occupied a narrow valley beyond the

Pachalur village across from where they were. You had to go

through the village and up the next hill. An indistinct path by

the side of the road took them through a crowd of cottonwood

trees, and on to a wide expanse of grass interspaced with rocks.

Standing here, it felt like you were on a shore, with the woods a

vast green sea stretched out below you. At the further end of

the meadow, rough steps hewn into the rock led them down

into the jungle. Slowly, they descended into it and left the

world behind.

At the bottom of the wide gully ran a playful stream of

crystal clear water. It skipped across the rocks and leaped over

a boulder into a bubbling pool of delight. It was so small, an

adult could hardly have done much with it, but it was just right2 Love and Hope

for Jasmine—her favourite spot. She sat chest deep in water

and let the stream cascade over her head and shoulders. Tall

trees spread a leafy canopy high above them. The stream and

forest bed got no direct sunlight, but it was bright; the very air

was suffused with a mystic green radiance.

As the afternoon wore on, things changed. Unknown to

them, fickle weather had turned face. It had become darker, as

though someone had dimmed the lights. “It’s enough, Jasmine,

you’ll catch a cold; come out,” shouted Usha.

Cocooned in her watery nest, Jasmine pretended not to

hear. Soon, her mother’s strong arms reached into her retreat

and pulled her out. She felt smothered as a bath towel

descended over her head; her scalp and hair were given a good

rub. The distant rumble of thunder made her mother stop

momentarily.

“There is rain coming, we must hurry, Jasmine,” said Usha

as she helped Jasmine into her clothes. They went up the forest

slope briskly. It somehow began to become bright again. When

they had almost reached the open meadow, Jasmine ran ahead;

something had caught her attention. Sunlight had burst in

through a rent in clouds and bathed the clearing with gold.

From below where her mother stood, it was as though Jasmine

had walked onto a floodlit stage. She was chasing a red and

black swallow-tailed butterfly. She reached for the sky as it

winged its way out of reach.

She glanced at her mother before taking off again around a

clump of rocks. This time, it was a pair of much smaller

butterflies. Their wings were lilac around the centre, melding

into a lemon yellow border. They cavorted in wild circles

around each other, like a pair of binary stars. They did not let

up one bit on their whirling dance as they gracefully swung

away from gleeful hands that reached out to them. They

disappeared over a clump of thick bushes at the edge of the

meadow, leaving Jasmine staring after them in awe and

wonder.

By this time, Usha had come up behind her.

“Don’t chase the butterflies away, Thangam.”

“Do you think they were friends, Amma? Why did they go

around each other?”

“Maybe they love each other, Thangam.”

Then, after a thoughtful gap, and almost to herself, Usha

said, “Love makes you do silly things, but it’s what keeps the

world going around.”

Jasmine did not know what made the world go around, but

she threw her arms around her mother’s waist and said, “I love

you, Amma!”

The rain caught up with them just as they reached the gates

of the campus. Jasmine had to be wiped dry all over again. But

she did not seem to mind as she smiled up at her mother and

gave her another hug.

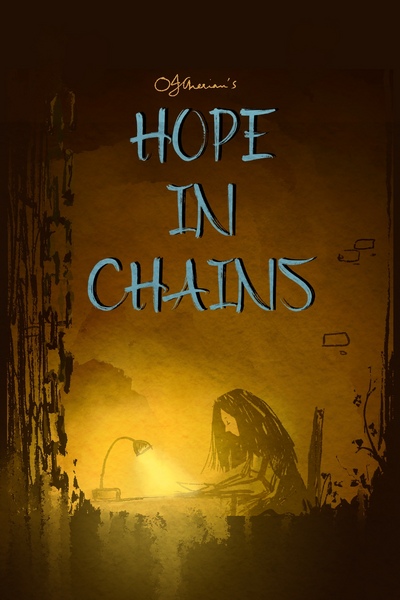

Later that night, Usha sat by herself at her desk. They had

returned from Leech Valley three hours ago. It was now three

weeks since Suresh had gone, and two years since their

wedding day. In her thoughts, the dates and hours had ceased to

exist, except as memorials to the life they had shared.

Usha sat, hunched and immobile. A small lamp lit up a

circle of light within which her delicate hands held a letter. And

now, as she straightened and stared vacantly into space, her

silhouette rose above the array of dim shadows that lined the

opposite wall. If anybody had seen her outline at that moment,

it would have been hard to forget. This face seemed to tell a

thousand tales of timeless sadness, and yet, with high cheeks4 Love and Hope

and pinched nose held up, it had a defiant beauty that

whispered ‘hope’.

Jasmine had gone to sleep and all was quiet. Outside,

beyond the fence, night sounds drifted in from the dark—the

chirping of crickets, the occasional croak of a toad. Far away, a

dog barked in fits and starts. Usha had not moved; her eyes

were still not focussed on anything in particular, but those

gateways to the mind bore witness to the grief inside, and filled

up with tears. When she looked down at the letter, it

overflowed like molten wax and dropped down on the page,

adding yet another smudge.

My dearest Usha,

If Dr Ravikumar has given you this letter and you are

reading these words, it means that I am well on my way.

In time, she folded the letter, returned it to its place in the

drawer, switched off the light and climbed into bed. She lay

awake in the darkness for a long time, and finally tossed and

turned her way into fitful sleep.

Many hours later, that familiar dream came knocking.

They formed the apices of a triangle, the three stars that

looked down at her from the southern sky. One of them was

smaller than the rest and very faint. The smell of the sea was

everywhere. Salt spray peppered her cheeks and mingled with

her tears, and both of them tasted the same when they came

down over her lips. Suddenly, the boat hit a swell and took a

jolt that jarred her spine; the next moment, she was in the

water. Now going down, she could still see the triangle of stars

through the blue water, which soon turned aquamarine, deep

green and inky grey. She felt her heart sink within her and findOby Cherian 5

depths that her body could never reach. I will never see him

again, was what she thought.

But this time, it was not her father’s face that came floating

up into her subconscious, it was Suresh’s. She could see him

clearly, and then it faded away and all was dark once more.

The sun came in through the eastern window and draped

itself in wavy rectangles over the table and across the floor. But

it was not the sun that awoke Usha the next morning. Grubby

little hands caressed her face.

“Amma, I am hungry,” whined Jasmine.

Like most children whose natural rhythms have not been

tampered by the trappings of civilisation, Jasmine had woken

up with the dawn. She slid out of bed and walked into a new

day. She had curly black locks hanging over both ears and dark

brown shining eyes. Her crème and chocolate skin was not as

dark as her mother’s, but not as light as her father’s (her

biological father, whom the child could hardly remember).

Most times, she was a vivacious little creature who could

charm the scowl off the most unfriendly face. She made them

smile, every one of them.

She went looking for her doll and found him face down on

the steel trunk that stood in a corner of the living room. She

picked him up on the way to the sofa, climbed on and knelt

beside the window. She placed him on the sill, looked out

blankly and said, “Will you also die one day, Tinto? Will you

become thin like Suresh Appa?

“My Appa died before I knew him. Grandmother says it’s

my bad luck because I was born on a Saturday. Is that true,

Tinto? Am I unlucky? Is it unlucky to be born on a Saturday?

When were you born, Tinto?”

Strange and weighty thoughts for a four-year-old, but have

them she did. Outside, the deep resonant call of a coucal made

her smile, and then the jolly face of Sindhu her friend came to

mind. She forgot all about death and dying. She stretched both

her arms high above her. Why does it feel so good to stretch?

she wondered. Soon, her stomach stirred inside her, reminding

her that she was hungry. She gently laid Tinto on the sofa and

went trudging into the next room to wake up her mother.

Usha stirred, opened her eyes and looked into her

daughter’s face.

“Oh, Thangam! Have you been awake for long? I am sorry.

Amma slept late today,” she said apologetically as she sat up,

raised her hands and tied up her loose hair into a rough knot.

She got up and walked to the bathroom. She splashed some

water on her gaunt face and looked in the mirror. She looked a

sight! I will have to hurry, thought Usha. She had a long day

ahead—breakfast for both of them and then she would have to

start packing. This was a large residence meant for doctors, but

now that Suresh was not there, she was not entitled to occupy it

any longer. Already, they had been kind to allow her to stay

three weeks. She would have to shift house today, to one of the

nurse’s quarters, about 200 metres away.

Perhaps it is just as well I am moving, she thought to

herself. It would have been difficult to be here in this place she

had shared with Suresh. It would be easier to start afresh in a

new house.

After breakfast, Jasmine went out into the garden with her

dolls and Usha was left alone. She went around from room to

room, not knowing where to begin. Memories beckoned to her

from every corner.

Yes, she would start with the kitchen—where there would

be little to remind her of Suresh—that would be the easiest. So

she set to work; the pots and pans would go into an old carton

and the bottles into another. In half an hour, she was almost

done with the kitchen, only the tidying-up to do. This she

would leave to the men. Veeran, the ward aide, had promised to

take half a day’s leave to help her shift.

She took a break, went out and sat on the porch. She heard

the nine-thirty bus labouring up the road. Murali, her brother,

would be on it. He lived in Kariyampatti, a small village on the

plains, and was now on his way up to help his sister shift

house. The road started from Oddanchatram, the market town

at the foot of the mountains. It slithered up the lower range of

hills before levelling off across the Parapalar valley at 1,000

feet. Having crossed the basin, it skirted the lake and climbed,

taking nine hairpin bends to the high ranges. Pachalur at 4,000

feet was the first large village on this mountain road that

reached further into the Western Ghats of southern India.

The morning sun seemed to give everything an extra dose

of life. The leaves reflected a vibrant green, the bees buzzed

around with added zest. Usha looked to her left to see a sunbird

flit across to a patch of garden, where it settled on a stem and

deftly dipped its long beak into one of the red trumpet-shaped

flowers. Behind this patch of coral flowers was the pine tree,

and towering above it in the distance was the peak of the Boar

Mountain. Wild boars had been sighted there in the past. How

often she had sat here with Suresh.

The Hill People’s Cooperative Hospital and its campus was

spread across five acres of gently sloping woods. It overlooked

the Pachalur village on its southern side and reached up north

to a broad ridge where the land fell away gradually into the

Reserve Forests below. The hospital occupied the lower ground

and the staff quarters took up the higher end of the campus.

The doctors’ residences stood towards the eastern edge of the8 Love and Hope

ridge, where the drop beyond was precipitous and therefore, the

view was incomparable. This was where Usha now sat. The

whole of the Parapalar valley was set out before you. Her eyes

settled on the silvery blue surface of the lake far below.

A river had once meandered through this vast valley,

disappearing over its north-western edge, running through a

narrow gorge before plummeting over a two-hundred-feet

waterfall to the flatlands below. Forty years ago, they had

thrown a gravity dam across this running water at the narrow

mouth of the gorge, piling back the water to form the swollen

Y-shaped lake that now shimmered in the distance. The valley

held this body of water in its hollow, as a cupped hand would

hold a bit of precious oil.

I am going to miss this view, thought Usha as she went

back into the house. She got a couple of suitcases down from

the ledge in the storeroom and carried them to the bedroom.

She opened the cupboard and arranged her clothes into one of

the suitcases. Then there were Jasmine’s dresses and finally, in

the topmost shelf, Suresh’s pile. She held a couple of his

underclothes close to her and thought a faint whisper of his

scent still lingered there. What would she do with his clothes?

She would allow Murali to choose the best of them and leave

the rest for Veeran.

After the cupboard, she shifted to the table. Piled on the

floor to one side were Suresh’s papers. Copies of review

articles, notes on various topics, some letters, a few papers he

had helped publish, important memos. All of them were

important, not just the memos. Important: until a few weeks

ago. All very precious: until a few months ago. Papers that

would never have been treated so carelessly now lay in an

untidy heap, waiting for the fire or rubbish dump. How

meaningless it all seemed, thought Usha. How irrelevant things

became with the passing of time. In a few weeks, everything

was forgotten as though someone never was, except in the

minds of a few dear ones, where remembrances were treasured

in bits and pieces for another few years.

There was the trunk full of medical books, which she

would donate to the hospital library. The stethoscope she would

keep. The other diagnostic tools she would give to Dr

Ravikumar.

Soon, Murali and Veeran arrived and things moved faster.

A trolley was used to shift the boxes, four or five at a time to

her new home. By 4 pm, the house was empty, except for the

bare furniture that belonged to it.

I have spent some of the best days of my life here, Usha

thought as she went from room to room for one last time.

She felt cramped in the new house. After shifting the

cartons and boxes to their appropriate places, Veeran departed.

She unpacked a few essentials and then made some tea. They

sat on the small portico, sipping the tea and watching the sun

go down.

“Do you have to go today, Anna?” Usha asked Murali.

“I have to catch the seven-thirty bus. I promised Shanthi I

would be back tonight.”

Poor Murali, thought Usha. Shanthi had him on a line, but

she was efficient and hard-working and looked after their

parents and his children well. What more could one ask for?

With a thin, weather-beaten face and balding hair going

grey in patches, Murali looked every one of his 39 years, and

perhaps a few more. He had a pointed moustache, sharp intense

eyes and a long scar on his left forearm.

Comments (0)

See all